The James Webb Space Telescope has spectroscopically confirmed MoM‑z14 as the most distant galaxy observed so far, with a redshift of 14.44 — light emitted about 280 million years after the Big Bang. The compact, luminous galaxy spans roughly 240 light‑years and shows intense star formation plus elevated nitrogen relative to carbon, a chemical signature similar to some globular clusters. The finding, published in the Open Journal of Astrophysics, deepens puzzles about early galaxy formation and points to more discoveries ahead from JWST and the upcoming Roman Space Telescope.

James Webb Breaks Its Own Record — Discovers Most Distant Galaxy Yet, MoM‑z14 (z=14.44)

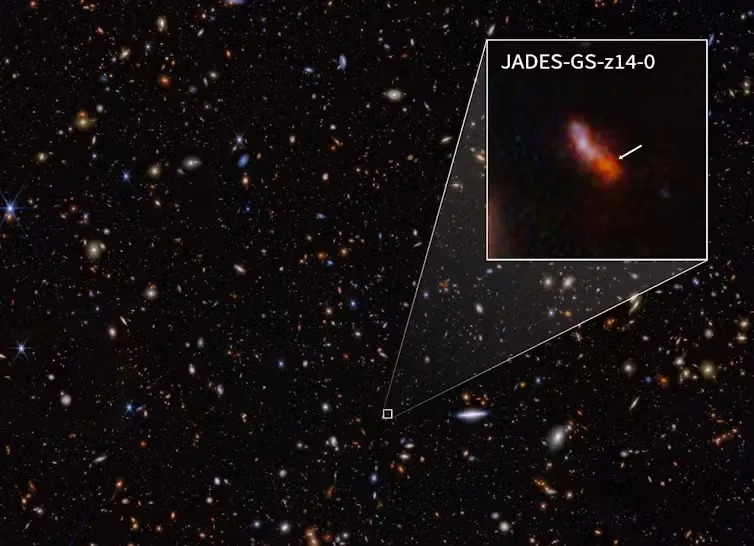

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has identified the most distant spectroscopically confirmed galaxy observed to date: MoM‑z14. The new measurement pushes direct observation to just 280 million years after the Big Bang, with a spectroscopic redshift of 14.44 — surpassing the previous record-holder, JADES‑GS‑z14‑0 (z = 14.18).

The discovery is reported in a study originally posted on arXiv on May 23, 2025, and later accepted for publication in the Open Journal of Astrophysics in January 2026. According to a NASA statement issued Jan. 28, 2026, lead author Rohan Naidu (MIT Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research) said, "With Webb, we are able to see farther than humans ever have before, and it looks nothing like what we predicted, which is both challenging and exciting." NASA confirmed the study's peer-reviewed acceptance.

Naidu and colleagues located MoM‑z14 by searching existing JWST imaging for promising high-redshift candidates and followed up with targeted spectroscopy in April 2025 to measure its distance precisely. Spectroscopic redshift — the stretching of light to longer, redder wavelengths as the universe expands — provides a direct estimate of how long that light has traveled. For MoM‑z14, the measured redshift indicates the light left the galaxy about 280 million years after the Big Bang.

Though bright, MoM‑z14 is compact: roughly 240 light‑years across, about 400 times smaller than the Milky Way, yet it has a mass comparable to the Small Magellanic Cloud, a dwarf companion to our galaxy. The team observed the galaxy during an intense burst of star formation and found a chemical signature showing elevated nitrogen relative to carbon — a pattern reminiscent of some Milky Way globular clusters. That similarity suggests at least some star‑formation processes seen locally may already have been underway in the very early universe.

Since JWST began operations in 2022, it has uncovered a larger-than-expected population of bright, ancient galaxies, prompting astronomers to revise models of early galaxy formation. The authors write that this unexpected population has "electrified the community" and raised fundamental questions about how galaxies assembled in the first 500 million years after the Big Bang.

Looking ahead, the Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope — an infrared mission designed for wide-area surveys and currently targeted for launch as soon as late 2026 — should identify many more high-redshift candidates. Meanwhile, the authors note that "previously unimaginable redshifts, approaching the era of the very first stars, no longer seem far away," and JWST itself is likely to extend the observational frontier further before Roman begins operations.

Why This Matters: Spectroscopic confirmation removes much of the uncertainty that can afflict photometric candidates; a confirmed z=14.44 object pushes empirical constraints closer to the epoch when the first stars and galaxies formed, helping refine theories of cosmic dawn.

Help us improve.