The PLOS One study compared evolution of a T7 bacteriophage and Escherichia coli on Earth and aboard the ISS, finding that microgravity slows infection but drives different mutations. Phages in space evolved enhanced receptor‑binding mutations while bacteria developed microgravity‑specific defenses. Researchers used those space‑driven adaptations to engineer phages with improved activity against antimicrobial‑resistant pathogens, including UTI‑causing E. coli, suggesting the ISS can help discover changes useful for phage therapy development.

Phages Evolve in Space — ISS Mutations Could Help Fight Antibiotic‑Resistant Superbugs

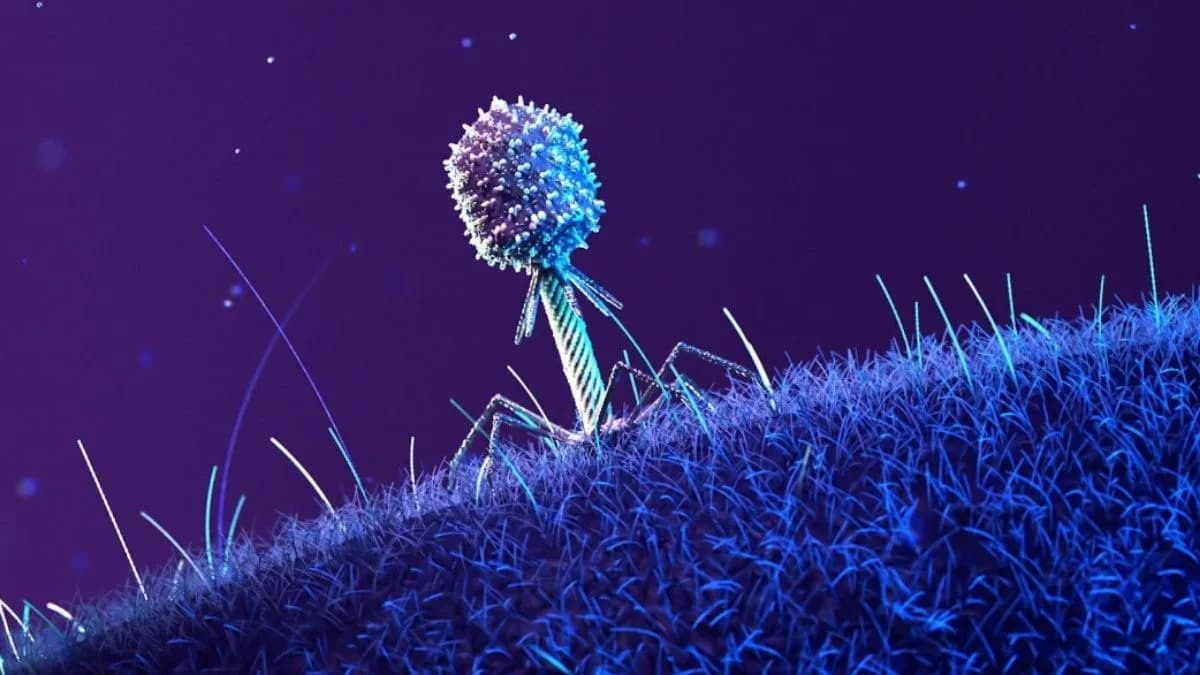

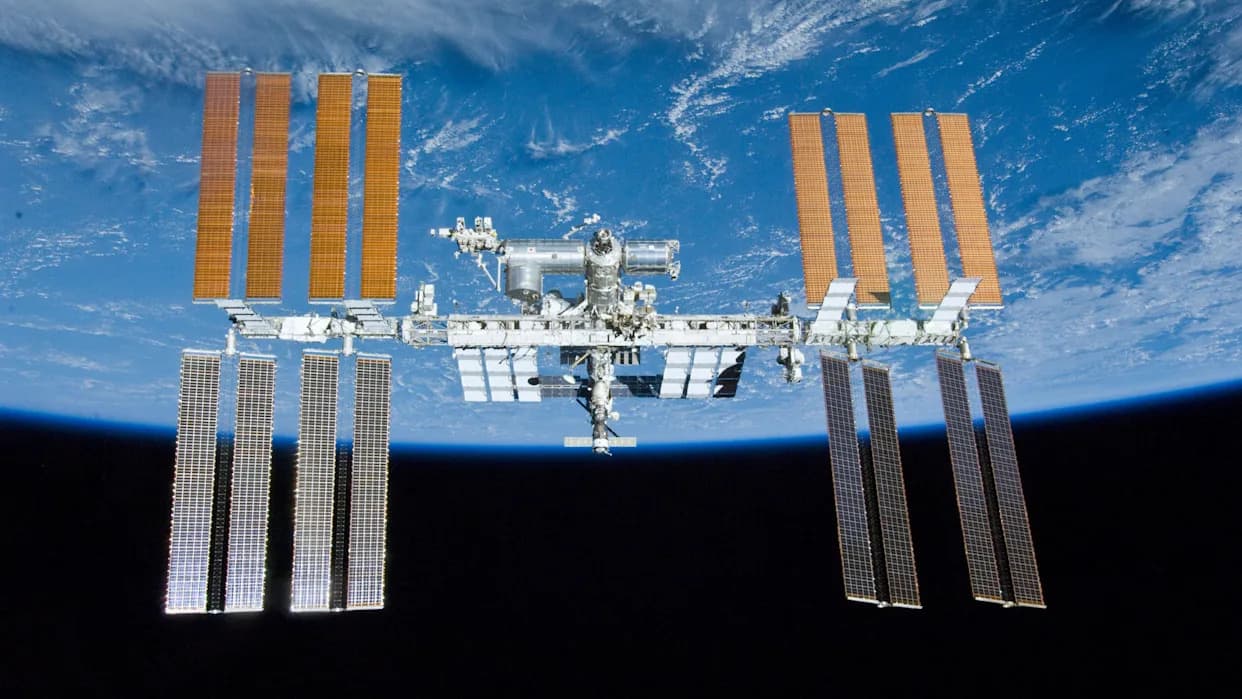

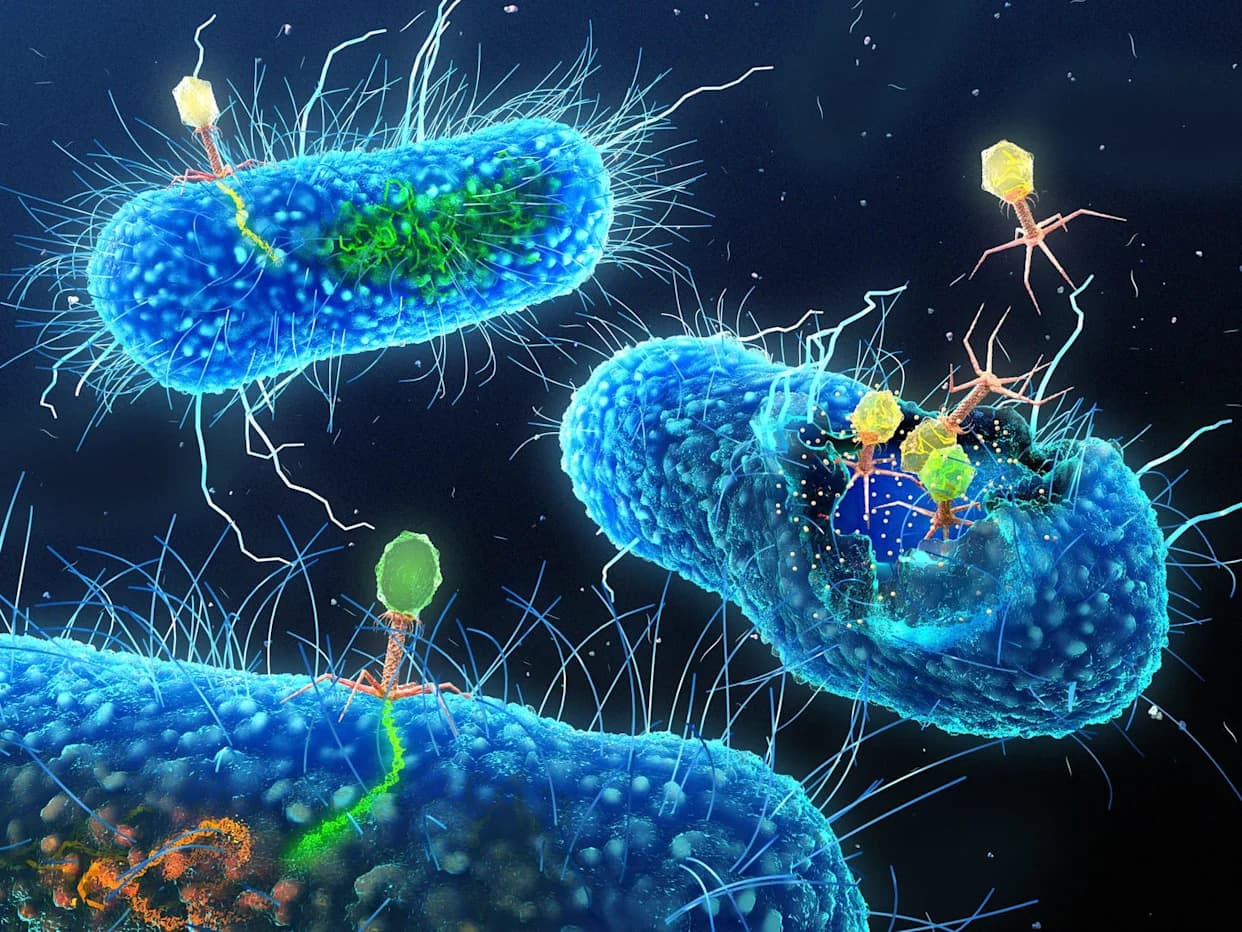

As antibiotic resistance rises worldwide, researchers are exploring bacteriophages—viruses that infect bacteria—as a complementary tool to fight drug‑resistant “superbugs.” A new study published in PLOS One reports that a T7 bacteriophage and its Escherichia coli host evolved along different paths when the interaction occurred aboard the International Space Station (ISS) compared with matched experiments on Earth.

Study Design and Methods

Scientists (including teams at the University of Wisconsin–Madison) infected two matched E. coli populations with the same T7 phage: one culture was kept on Earth, the other was sent to the ISS. The team tracked evolutionary changes over time using whole‑genome sequencing and deep mutational scanning to capture detailed genetic adaptations in both the phage and the bacteria.

Key Findings

Although the phage ultimately overcame its bacterial host in both environments, the dynamics and mutations differed markedly:

- In microgravity, phage infection proceeded more slowly than on Earth, but phages accumulated mutations that improved receptor‑binding proteins—changes that can increase the ability to attach to and infect bacterial cells.

- E. coli populations evolving in microgravity developed distinct, space‑specific mutations that conferred greater resistance to phage attack under those conditions.

- By studying the space‑driven adaptations, researchers were able to design engineered phages with enhanced activity against antimicrobial‑resistant pathogens back on Earth, including E. coli strains that cause urinary tract infections.

Why This Matters

The World Health Organization lists antimicrobial resistance (AMR) among the top global health threats. Bacteriophages are natural drivers of bacterial diversity and have potential as targeted therapeutics against AMR bacteria. The ISS provides a unique experimental environment—microgravity and elevated cosmic radiation exposure—that can reveal mutation pathways and binding changes not commonly observed on Earth.

“Space fundamentally changes how phages and bacteria interact: infection is slowed, and both organisms evolve along a different trajectory than they do on Earth,” the authors note, emphasizing that space‑driven insights can inform engineering of more effective phages for terrestrial medicine.

Broader Context and Next Steps

Using space environments to explore genetic variation is an emerging strategy: for example, the IAEA has sent seeds to the ISS to accelerate useful crop mutations. This phage study suggests orbiting laboratories could similarly accelerate discovery of therapeutic mutations that help design stronger, more specific phage therapies. Future work will need to test engineered phages in clinical and real‑world settings and to further clarify how microgravity and space radiation jointly influence mutation patterns.

Overall, the research highlights the ISS as more than a platform for physics and astronomy: it can be a valuable laboratory for discovering biological mechanisms that may translate into better tools against AMR on Earth.

Help us improve.