The James Webb Space Telescope imaged the remnants of stellar mergers that produced luminous red novae and found the merger products resemble cool, very large red supergiant stars. Researchers studied nine events from archival data and examined two clear cases — AT 2011kp and AT 1997bs — observed 12 and 27 years after their eruptions. JWST infrared spectra show the surrounding dust is carbon-rich (graphite-like), suggesting these mergers help seed the interstellar medium with organic-building material.

JWST Reveals That Merged Stars Become Cool, Giant “Red Supergiant” Remnants — And Seed the Galaxy With Carbon-Rich Dust

Astronomers using the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) have identified what remains after two stars collide and merge in an explosion known as a luminous red nova. By combining JWST infrared observations with archival Hubble and Spitzer data, researchers found that the merger products resemble very large, cool red supergiant stars and that the material ejected in these events is rich in carbon compounds that can help seed the interstellar medium with life-forming ingredients.

Rapid Transients Offer a Rare Look at Stellar Evolution

Unlike slow cosmic processes that unfold over millions of years, transients such as supernovae, black hole mergers and luminous red novae evolve on human-observable timescales — from seconds to decades. That relative speed allows astronomers to watch the dramatic final stages of binary systems as they coalesce and to study both the eruption and the long-term remnant.

“We don't normally witness the evolution of a system over millions of years, but these pairs of stars are experiencing the final moments before their collision, which instead occurs much more rapidly,” said Andrea Reguitti of the Istituto Nazionale Di Astrofisica (INAF). “The resulting transient has evolutionary times comparable to those of a supernova — that is, a few months.”

How the Team Studied the Remnants

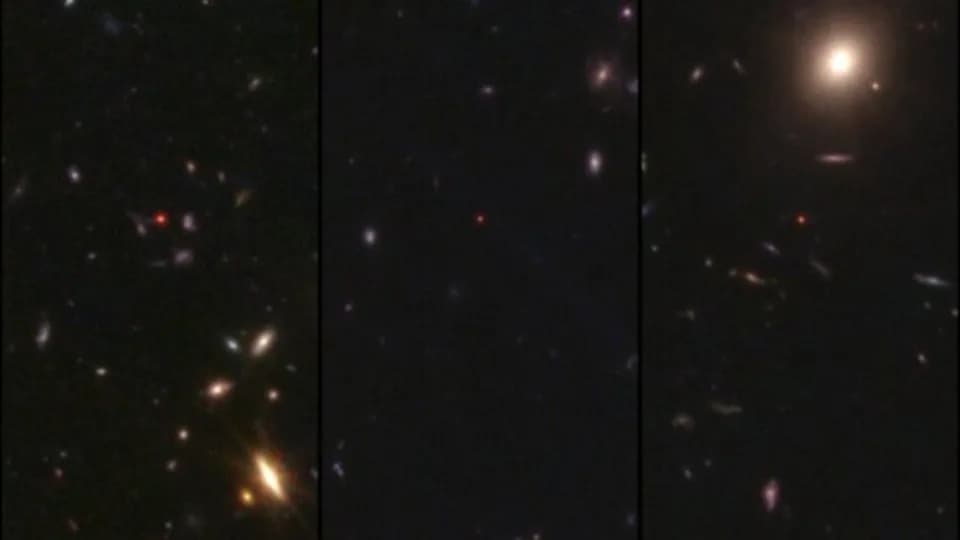

Reguitti and colleagues surveyed archival observations and selected nine luminous red nova events for follow-up. Of those, two provided clear pre- and post-merger views: AT 2011kp (discovered in 2011, in a galaxy roughly 25 million light-years away) and AT 1997bs (erupted in a galaxy about 31 million light-years away). The team combined JWST infrared data collected in 2023–2024 with older Hubble and Spitzer images to observe the late-time evolution of these objects — 12 years after the merger for AT 2011kp and 27 years after for AT 1997bs.

Remnants Look Like Cool, Massive Red Supergiants

The late-time observations revealed that the merged objects have the large radii and cool surface temperatures typical of red supergiant stars: hundreds of times the Sun's radius. If placed at the center of our Solar System, such a star would engulf the inner rocky planets and reach near Jupiter's orbit. Despite their enormous sizes, these remnants are relatively cool, with surface temperatures estimated between about 3,200 and 3,700 °C (roughly 5,800–6,700 °F), compared with the Sun's surface temperature of about 5,500 °C (~9,900 °F).

“We didn't expect to find this type of object as a result of the merger,” said team member Andrea Pastorello (INAF). “We would have expected a hotter, more compact source after two stars combined, not such a cool, expanded remnant.”

Carbon-Rich Dust: A Potential Source of Life’s Building Blocks

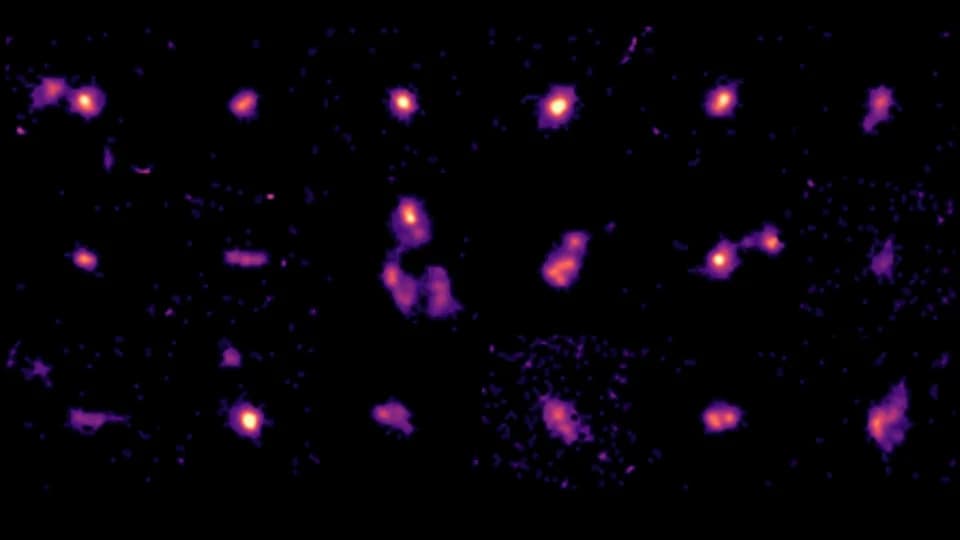

JWST's infrared spectra also allowed the team to probe the composition of the dust surrounding the newborn stars. The dust appears dominated by carbonaceous compounds — such as graphite — which are important components of organic chemistry. Individual luminous red novae can eject dust masses roughly equivalent to a few hundred Earths (the team cites values on the order of ~300 Earth masses), so these events may be a significant source of carbon-rich dust in galaxies.

That finding supports the poetic but scientifically grounded idea that some of the raw materials for planets and life are distributed across the galaxy by explosive stellar events: “We are made of carbon compounds, the same carbon that this dust is rich in,” Reguitti said. “It's a different way of telling the old story that we are ‘stardust.’”

Implications and Publication

The results show that stellar mergers can produce unexpectedly cool, bloated stars and contribute substantial quantities of carbonaceous dust to the interstellar medium. The team's paper is scheduled for publication in the journal Astronomy & Astrophysics.

Help us improve.