New spectroscopic analysis of tiny red sources detected by the James Webb Space Telescope shows that most "little red dots" are young, gas-shrouded black holes rather than infant galaxies. Roughly 70% exhibit high-velocity orbiting gas, and the objects appear within a few hundred million years after the Big Bang but fade by about one billion years after the Big Bang. Many of these early black holes have masses near ten million times that of the Sun, offering fresh insight into how massive black holes grew in the early universe.

Solved: JWST's "Little Red Dots" Are Young, Gas‑Shrouded Black Holes

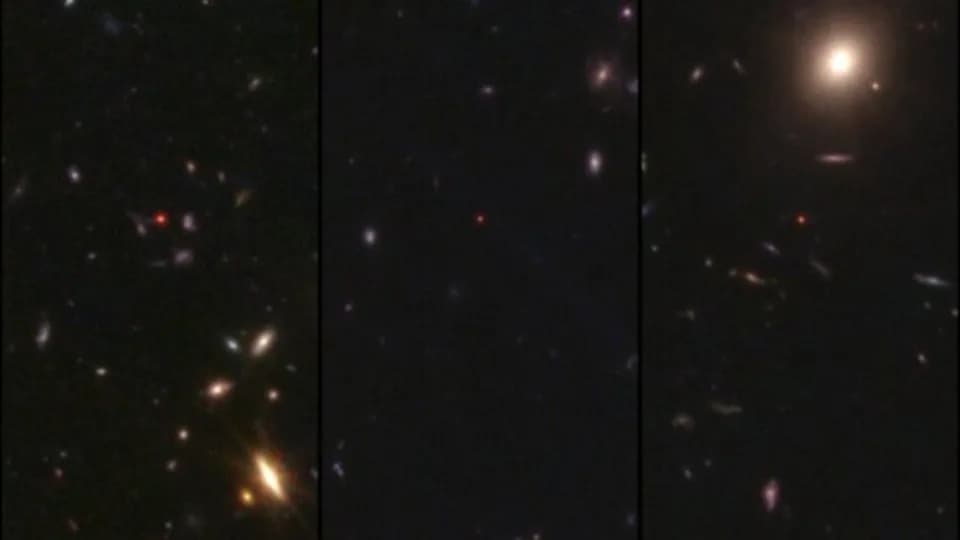

When the James Webb Space Telescope returned its first deep-field images, astronomers noticed tiny crimson points scattered across the early universe — the so-called "little red dots" (LRDs). After two years of spectroscopic follow-up led by the Niels Bohr Institute's Cosmic Dawn Center in Copenhagen, researchers now identify most of these LRDs as young, actively accreting black holes.

Some teams initially suggested the sources might be infant galaxies because they emitted light. However, galaxy formation is relatively slow: these objects appear within a few hundred million years after the Big Bang and fade by roughly one billion years after the Big Bang, a timeline that makes it unlikely they are mature, starlight-dominated galaxies. Their unusually deep red color also does not match the spectrum expected from stars alone.

Over the past two years the Copenhagen team used spectroscopy to probe the LRDs' light in detail. About 70% of the sources show clear signatures of gas orbiting at very high speeds — a classic sign of material swirling around a compact, massive object. Dense clouds of gas enshroud the sources; as material spirals inward it heats dramatically and emits bright radiation. Combined with the great distances (high cosmological redshift), that emission appears deep red to JWST.

"The little red dots are young black holes, enshrouded in a cocoon of gas that they are consuming to grow larger," said Darach Watson, a co‑author of the study. "As gas spirals in it becomes extremely hot and bright. Only a small fraction is swallowed — much of the inflow is expelled from the poles, which is why black holes can be 'messy eaters.'"

These early black holes are much less massive than the billion-solar-mass behemoths in mature galactic centers, yet they remain substantial: current estimates put many LRDs at roughly ten million times the mass of the Sun. Identifying LRDs as accreting black holes helps explain how large black holes could grow quickly in the universe's first billion years and provides new constraints on theories of early black hole and galaxy formation.

What Comes Next

Follow-up spectroscopy and deeper JWST observations will refine mass and growth-rate estimates, reveal how common such objects were, and test whether all LRDs share the same evolution. These data will be crucial for understanding the rapid assembly of massive black holes and their role in shaping the first galaxies.

Help us improve.