The James Webb Space Telescope has spectroscopically confirmed a luminous galaxy, MoM-z14, that formed about 280 million years after the Big Bang (redshift 14.44). Webb’s measurements show the early universe hosted many more bright, massive galaxies than pre-launch models predicted—perhaps ~100× more—forcing a rethink of early galaxy formation. MoM-z14’s elevated nitrogen and signs of clearing surrounding hydrogen provide new clues to rapid chemical enrichment and the timing of cosmic reionization.

James Webb Confirms Galaxy From 280 Million Years After the Big Bang, Challenging Early-Universe Models

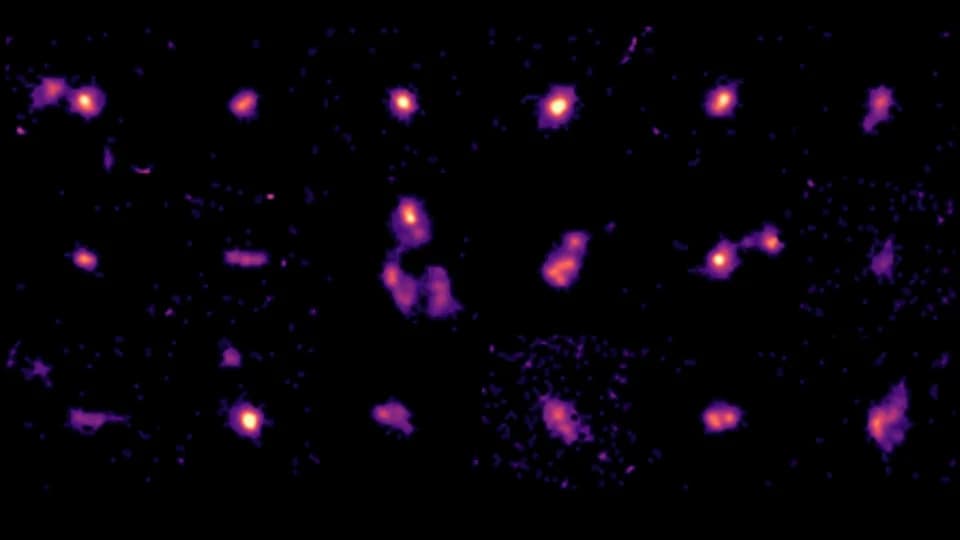

NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope has spectroscopically confirmed a surprisingly bright galaxy that formed roughly 280 million years after the Big Bang, pushing direct observations deeper into the universe’s infancy than ever before.

The galaxy, designated MoM-z14, was verified with Webb’s Near-Infrared Spectrograph (NIRSpec), which measured a redshift of z = 14.44. That redshift implies the light now reaching Earth has been traveling through expanding space for about 13.5 billion years, corresponding to when the universe was only a few percent of its current age.

“With Webb, we are able to see farther than humans ever have before, and it looks nothing like what we predicted,”

— Rohan Naidu, lead author, MIT’s Kavli Institute for Astrophysics and Space Research

Imaging alone could not establish MoM-z14’s true distance and age. Astronomers used spectroscopy to measure its redshift and chemical signatures — a critical step for studies of objects this early in cosmic history.

“When you’re looking this early, estimates aren’t enough. Spectroscopy tells us exactly what we’re seeing and when it existed,”

— Pascal Oesch, University of Geneva, co-principal investigator

MoM-z14 is part of a growing sample of unexpectedly luminous early galaxies Webb has uncovered. The research team estimates the abundance of such bright galaxies may be roughly 100 times higher than pre-Webb theoretical models predicted, a discrepancy that is prompting astronomers to rethink how quickly structure formed after the Big Bang.

One striking result from the NIRSpec data is MoM-z14’s chemical composition: the galaxy shows elevated nitrogen levels despite forming so soon after the Big Bang. Under standard stellar-evolution scenarios, multiple generations of stars would normally be required to produce this level of nitrogen.

To explain these heavy-element signatures, researchers propose that conditions in the early universe may have favored the formation of extremely massive, short-lived stars that manufactured heavier elements much faster than typical stars today.

Observations also indicate MoM-z14 is actively clearing neutral hydrogen from its surroundings, providing new clues about the timing and progress of cosmic reionization — the era when the first luminous sources ionized the dense hydrogen fog and allowed ultraviolet and visible light to travel freely.

Mapping that transition was one of Webb’s primary science goals; until now, direct data from this epoch have been limited. Webb’s confirmation of MoM-z14 builds on earlier Hubble discoveries such as GN-z11 (about 400 million years after the Big Bang), and Webb has since pushed the frontier even earlier.

Looking ahead, astronomers expect the upcoming Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope to complement Webb by surveying vastly larger sky areas and potentially identifying thousands of similar early galaxies. As one team member put it, Webb provides the depth and detail, while Roman will deliver the scale needed to understand population statistics.

The James Webb Space Telescope is operated by NASA in partnership with the European Space Agency (ESA) and the Canadian Space Agency (CSA). The discovery of MoM-z14 not only adds a remarkable data point to galaxy catalogs but also forces a rethinking of how rapidly galaxies formed and chemically enriched the cosmos after the Big Bang.

Source: NASA; study published in the Open Journal of Astrophysics.

Help us improve.