Researchers combined over 40 years of behavioral records with DNA methylation data from 38 precisely aged male Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins in Shark Bay, Australia. Using multiple epigenetic clocks — including one calibrated for this population — they found males with stronger, long-term social bonds appeared biologically younger than more solitary males. The study emphasizes relationship quality rather than group size and suggests social bonds may help buffer stress and influence aging, while noting the results show correlation, not proven causation.

Strong Dolphin Friendships Linked to Slower Biological Aging

Watching dolphins play often inspires wonder — and new research suggests their deepest friendships may do more than delight observers: they may slow biological aging.

Scientists analyzed more than four decades of behavioral records from a well-studied community of Indo-Pacific bottlenose dolphins in Shark Bay, Australia, and combined those observations with molecular data to investigate whether social relationships influence biological aging.

How the Study Was Done

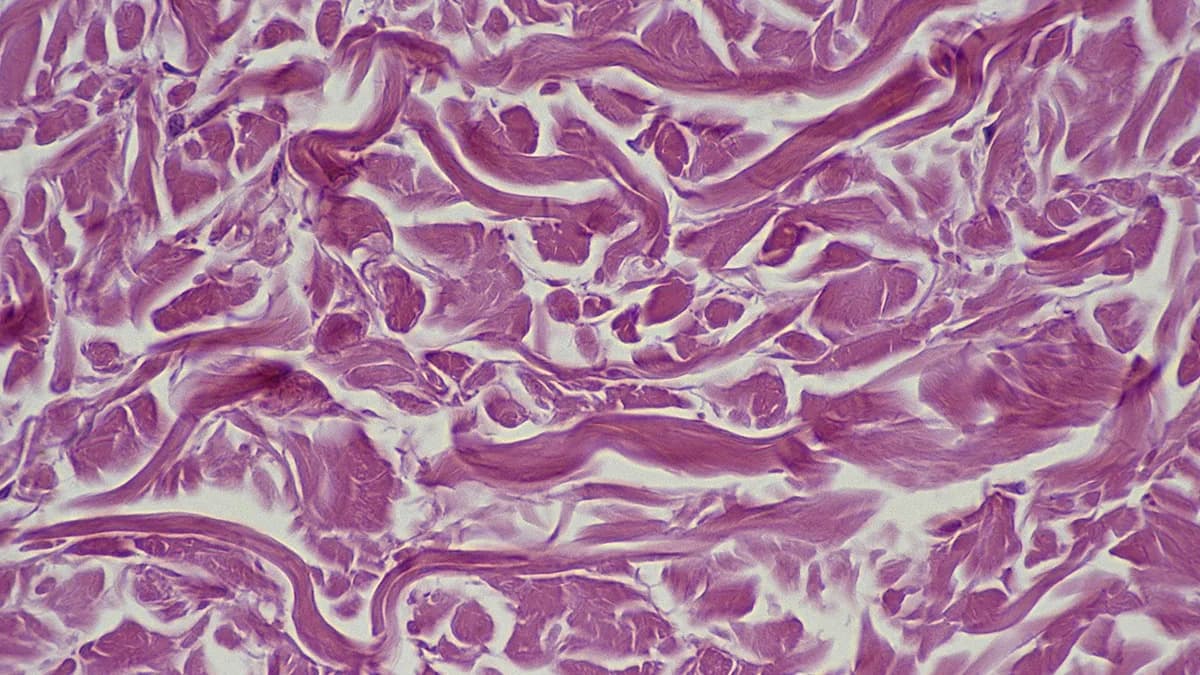

The team focused on 38 male dolphins whose chronological ages are precisely known. Researchers collected skin samples and measured DNA methylation patterns — chemical tags on the genome that help regulate gene activity — then applied multiple epigenetic clocks. These clocks, including one calibrated specifically for the Shark Bay population, estimate biological age from predictable changes in DNA methylation that accumulate over an animal’s lifetime.

Key Findings

Individuals that maintained stronger, long-term social partnerships appeared biologically younger than more solitary males when assessed by epigenetic markers. The association held when the researchers used population-calibrated epigenetic clocks, strengthening the link between sociality and biological aging in this population.

“Aging is a complex process that includes DNA damage [such as] double-strand DNA breaks — it’s not just the mitochondria working faster or being exhausted or suddenly having a lot of mutations,” said lead author Livia Gerber, then a postdoctoral fellow at the University of New South Wales in Sydney.

Other work in dolphins and other mammals links positive social interaction to increased oxytocin release, a hormone tied to bonding and stress reduction. Conservation veterinarian Ashley Barratclough, who was not involved in the study, suggests social bonds may buffer stress and thereby slow biological aging across mammals.

Implications and Caveats

Importantly, the study found that the quality of relationships — not simply group size — correlated with slower epigenetic aging. In fact, some forms of large-group sociality may be stressful and could have the opposite effect. The results raise possible conservation implications: protecting social structures and opportunities for meaningful interactions could support dolphin health.

However, the authors and external experts emphasize caution: the study shows an association, not definitive proof that social bonds cause slower aging. More research is needed to clarify mechanisms, test causality and explore whether similar patterns hold across sexes, other populations and other species.

Bottom line: In Shark Bay, male dolphins with stronger, long-term friendships show signs of being biologically younger — a finding that highlights the potential health value of close social bonds in animals as well as humans.

Help us improve.