The Greenland shark appears to preserve retinal structure and DNA integrity throughout its unusually long life, according to a study published in Nature (January 2026). Researchers analyzed eyes collected near Disko Island (2020–2024) and found rod-only retinas with densely packed photoreceptors, intact retinal layers and no evidence of DNA fragmentation. Transcriptomic data showed strong expression of DNA-repair genes while cone-vision genes were inactive, suggesting active maintenance mechanisms that may inform research into human age-related vision loss.

How Greenland Sharks Preserve Sharp Vision for Centuries — Clues from DNA Repair

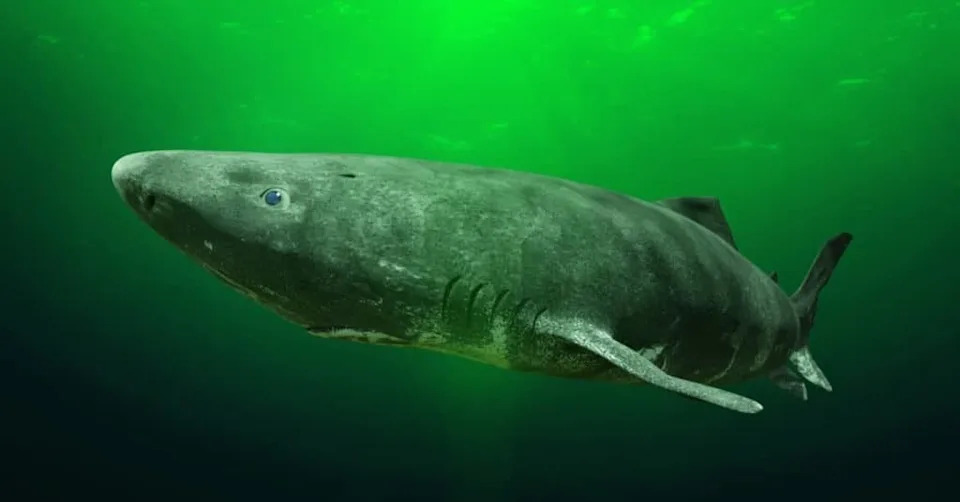

The Greenland shark (Somniosus microcephalus) appears to retain clear, functional eyesight for centuries — a remarkable adaptation that may point to molecular strategies for protecting vision in aging humans. New research published in Nature (January 2026) examined eyes from Greenland sharks caught near Disko Island and found intact retinal structure, no evidence of DNA fragmentation, and strong expression of DNA-repair genes across exceptionally long lifespans.

Research Overview

Scientists from the University of Basel, University of California, Irvine, University of Copenhagen, Indiana University South Bend and the Virginia Institute of Marine Science analyzed eyeballs collected from sharks captured between 2020 and 2024 on long lines near the University of Copenhagen’s Arctic Station on Disko Island. The eyes were fixed, frozen and studied with a broad suite of techniques, including genomics, transcriptomics, in situ hybridization (RNAscope), ultramicrotomy, chromatin staining, mass spectrometry, in vitro opsin regeneration and spectrophotometry.

Key Findings

Rod-Only Retina: Greenland shark retinas are composed exclusively of rod photoreceptors (no cones), a structure suited to low-light, deep-water environments. The rod cells are densely packed and elongated, similar to specializations seen in other deep-dwelling or nocturnal species.

Intact Retinal Layers and No DNA Fragmentation: Microscopic and molecular analyses revealed intact retinal layers with no signs of degeneration. Tests for DNA fragmentation — a common marker of cell death and aging in many vertebrate tissues — found no detectable retinal DNA damage even in sharks more than a century old.

Active DNA Repair and Suppressed Cone Genes: Transcriptomic analysis showed strong expression of DNA-repair–associated genes in the retina, while genes associated with cone-based (bright-light) vision were largely inactive. Together, these patterns suggest a long-term, active maintenance program that preserves photoreceptors and genomic integrity.

Why This Matters

Greenland sharks live in very cold (down to −1.1 °C), high-pressure deep waters (approaching 9,500 feet) and may have their corneas obscured by parasitic copepods — conditions that would typically promote retinal degeneration in other species. Yet these sharks retain functional vision and are capable of hunting fast-moving prey such as seals, implying effective visual performance in dim environments.

Implications for Human Eye Health

The findings do not imply an immediate therapy for human eye disease, but they highlight biological strategies — notably enhanced DNA-repair pathways and long-term retinal maintenance — that could inspire new research into preventing or slowing age-related retinal degeneration such as macular degeneration and certain forms of photoreceptor loss.

Conclusion: The Greenland shark’s rod-dominated retina, dense photoreceptor packing and robust DNA-repair activity together support effective sight for centuries. Understanding these mechanisms may point to protective strategies relevant to human vision and aging.

Study published in Nature, January 2026. Tissue samples were collected near Disko Island (2020–2024).

Help us improve.