Theobromine, an alkaloid abundant in cocoa beans, was associated with molecular markers of slower biological aging in a King’s College London study of 1,669 people. Researchers measured blood levels of dietary metabolites and two DNA methylation–based aging indicators, including a telomere-related estimator. Theobromine was the only compound that showed a significant association after controlling for other cocoa and coffee chemicals, but the study is observational and does not prove causation.

Could Dark Chocolate Slow Aging? Study Links Theobromine To Younger Biological Profile

Good news for dark chocolate fans: a new study led by researchers at King’s College London (KCL) reports that higher blood levels of theobromine—a naturally occurring alkaloid in cocoa—were associated with molecular signs of slower biological aging.

What the Study Did

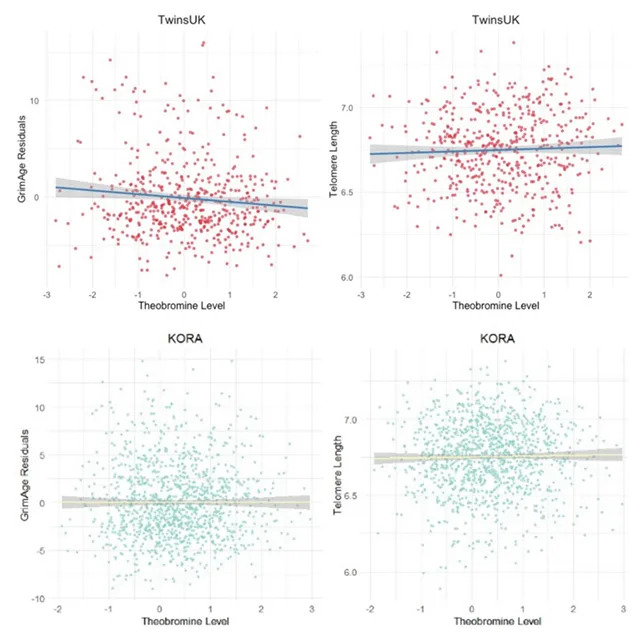

The team analyzed blood samples from 1,669 people drawn from two separate registries. They measured concentrations of metabolic breakdown products for dietary compounds such as caffeine and theobromine, and assessed two DNA methylation–based aging indicators: a genome-wide methylation clock and an estimator related to telomere length (chromosomal end caps).

After adjusting for other chemicals found in cocoa and coffee, theobromine was the only compound that showed a statistically significant association with a younger biological profile.

What This Means

These results suggest theobromine is a promising candidate for further research into how everyday dietary metabolites might influence aging at the molecular level. However, the study is observational and cannot prove cause and effect. The authors caution that sweetened or calorie-dense chocolate has health downsides, and any potential benefits of theobromine are likely to be most meaningful as part of a balanced diet.

"Our study finds links between a key component of dark chocolate and staying younger for longer," says Jordana Bell, an epigenomics researcher at KCL.

"The next important questions are what is behind this association and how can we explore the interactions between dietary metabolites and our epigenome further?" says clinical geneticist Ramy Saad.

Limitations And Next Steps

Because theobromine levels were measured in blood and the study design is observational, it cannot determine whether theobromine directly slows aging. Mechanistically, alkaloids such as theobromine can interact with molecular systems that regulate gene activity, which could plausibly affect aging processes, but detailed human data are limited. Future studies should test causal effects, investigate dose and food-matrix interactions (for example with polyphenols), and explore whether theobromine’s association holds in diverse populations.

The research has been published in the journal Aging.

Help us improve.