The Leonardo da Vinci Project used minimally invasive dry swabs on letters and a disputed drawing called "Holy Child" to search for genetic traces because no authenticated remains exist. Researchers detected diverse environmental DNA and a matching male Y‑chromosome sequence assigned to haplogroup E1b1, consistent with Tuscan origins. The findings come from a January 6 preprint and are preliminary—experts stress contamination and attribution challenges. Further sampling of less‑handled artifacts, living paternal descendants and authenticated bones would be needed to confirm any link to Leonardo and to explore genetic traits such as visual acuity.

Researchers Find Y‑Chromosome Clues on Artifacts Linked to Leonardo da Vinci — Could His DNA Be Retrieved?

Scientists are taking a novel approach to an age‑old mystery: can traces of Leonardo da Vinci’s DNA be recovered from objects he handled? With no confirmed human remains to test—his supposed grave in Amboise was destroyed in the French Revolution and any reburied bones remain unverified—researchers in the Leonardo da Vinci Project turned to artworks, letters and other artifacts for biological traces.

What the Team Did

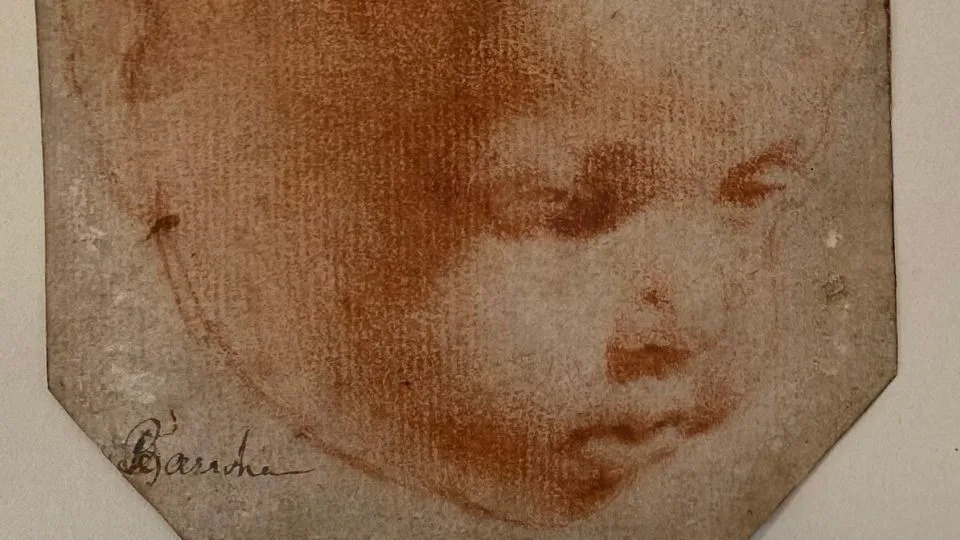

Rather than destructive sampling, the team tested minimally invasive techniques and selected dry swabbing as the safest method that still yields recoverable DNA. They applied this method to letters written by a distant relation of Leonardo and to a disputed drawing known as "Holy Child," which some experts have attributed to Leonardo and others have not.

Key Findings

Analysis of the swabs detected a wide range of environmental DNA—bacteria, fungi, plant and animal material—reflecting centuries of storage and handling. Importantly, the researchers also reported a matching male Y‑chromosome sequence on one of the letters and on the drawing. Using a panel of ~90,000 Y‑chromosome markers, that sequence was assigned to haplogroup E1b1, a lineage today found at modest frequencies in Tuscany.

Important caveat: The results come from a January 6 preprint that has not yet been peer reviewed. The authors explicitly do not claim definitive proof that the DNA came from Leonardo.

Context And Interpretation

The presence of plant DNA (including citrus) and wild boar sequences on the drawing correspond with historically plausible sources—Mediterranean orange trees (notably cultivated in Renaissance Tuscany) and boar‑hair paintbrushes commonly used by artists of the period. These environmental signals lend contextual support to an Italian origin for the material, but they are not proof of authorship.

The Y‑chromosome result is potentially useful because Y DNA traces paternal lineage. The team handled sampling and analysis carefully—women performed the swabs to reduce recent male contamination risks, and sequence analysis was done blind to sample identity. Still, multiple experts emphasize that DNA on an object can represent many hands over centuries and that establishing an exclusive link to Leonardo requires additional lines of evidence.

Expert Responses And Limitations

Some art historians questioned the choice of materials—arguing that documents directly linked to Leonardo or close paternal relatives would be more informative than items of disputed attribution. Geneticists noted that assembling Leonardo’s genome will likely require authenticated remains or verified descendants for comparison, plus repeated detection of the same Y‑chromosome pattern across many independent samples.

Other methodological suggestions include gentle brushing as a further noninvasive collection method and targeted enrichment panels to isolate and amplify human DNA more effectively for kinship and phenotype analysis.

Next Steps

Ongoing efforts include swabbing less‑handled notebooks and drawings held in France, sampling living descendants of Leonardo’s father where available, and testing the bones long rumored to be his—if they can be authenticated. The researchers hope that converging evidence—consistent detection of E1b1 across artifacts, paternal descendants and any authenticated remains—could establish a high‑probability paternal signature for Leonardo.

Why It Matters

Beyond authorship questions, a verified genetic profile could allow researchers to investigate hypotheses about Leonardo’s biology—such as exceptional visual acuity—by comparing his markers to known genetic variants linked to vision and neurocognitive traits. But such work remains speculative until strong genetic provenance is established.

Bottom line: The study introduces a careful, minimally invasive method and reports intriguing preliminary genetic signals linked to Tuscany and to a male Y chromosome (E1b1). Those signals are promising but not yet conclusive; confirming Leonardo’s DNA will require more samples, independent replication, authenticated remains or verified descendants, and peer review.

Help us improve.