Researchers swabbed a red‑chalk drawing attributed to Leonardo da Vinci and compared DNA traces to letters from a known male relative. Both artifacts contained Y‑chromosome markers assigned to haplogroup E1b1b, a lineage linked historically to Tuscany. While the finding is suggestive, the authors stress the match is not definitive—samples show mixed contributors and further sampling and permissions are needed to validate any claim that the DNA belongs to Leonardo.

Scientists Close In On Possible Leonardo da Vinci DNA After Y‑Chromosome Fragments Found on Red‑Chalk Drawing

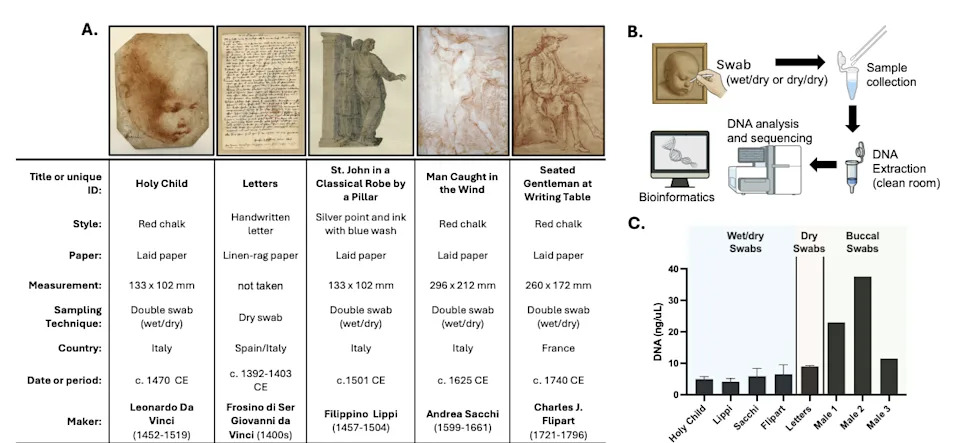

Researchers working with the Leonardo da Vinci DNA Project report they have recovered matching Y‑chromosome fragments from a red‑chalk drawing possibly attributed to Leonardo da Vinci and from letters written by a known male relative. The study—posted as a preprint on the BioRxiv server—uses minimally invasive swabbing and shotgun metagenomic sequencing to tease out tiny traces of DNA from a complex, centuries‑old biological mix.

What the team did

In April 2024, lead author Norberto Gonzalez‑Juarbe and colleagues gently swabbed a red‑chalk drawing titled "Holy Child," which had been in the private collection of the late art dealer Fred Kline for about 20 years. The team also sequenced DNA from letters known to have been handled by a male relative of da Vinci. After lab extraction and shotgun sequencing, the researchers compared human and nonhuman DNA fragments across samples and against reference databases.

Key findings

The authors report that both the drawing and the letters contained Y‑chromosome markers classified within haplogroup E1b1b, a broad male‑line lineage with historical roots in Tuscany—the region where Leonardo was born. Most of the genetic material recovered from the drawing (about 99%) was microbial or plant DNA, but among the human sequences the researchers observed Y‑chromosome segments consistent across the two artifact types. The team also detected nonhuman DNA such as Citrus sinensis (sweet orange) and fragments of Plasmodium, which together align with environmental and historical signatures from Renaissance‑era Tuscany.

“Together, these data demonstrate the feasibility as well as limitations of combining metagenomics and human DNA marker analysis for cultural heritage science,” the team writes in the preprint.

Controls and limitations

The researchers took steps to control for modern contamination. They obtained a 23andMe profile from Fred Kline (the drawing's recent owner) to exclude his genetic signature from the results. Nevertheless, the authors emphasize that the samples show mixed profiles consistent with handling by multiple people over time, and they caution that the current evidence cannot definitively identify Leonardo himself.

Y chromosomes are passed from father to son and can link male‑line relatives, but matching a haplogroup (even one traced to Tuscany) is not the same as a direct, unique identification. The authors call for additional sampling of confirmed da Vinci artifacts and broader comparative data to validate the tentative association.

Why this matters

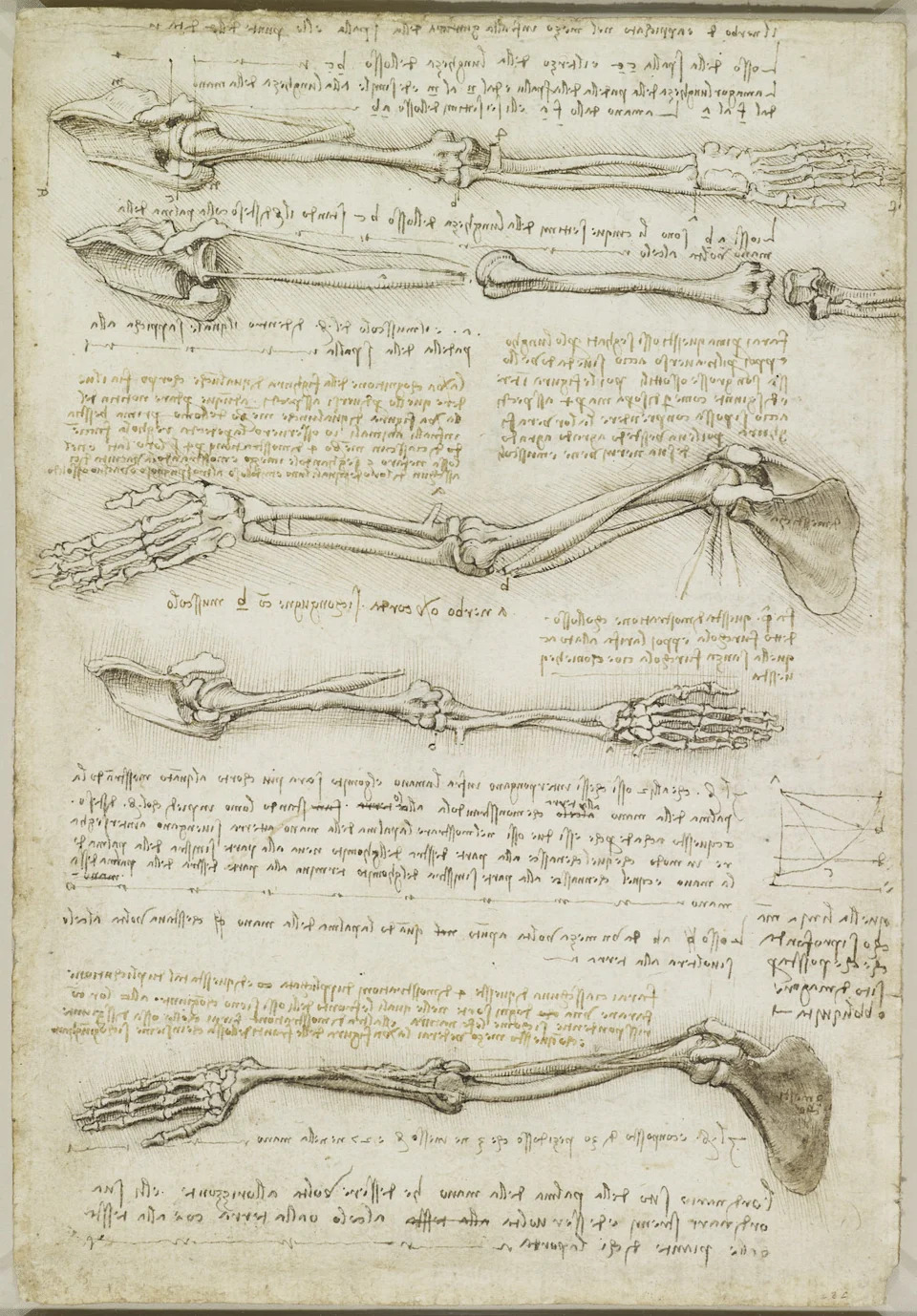

The study illustrates how modern genetics—shotgun sequencing and metagenomics—can complement traditional connoisseurship and conservation science by revealing biological traces left on artworks. If Leonardo’s genome could eventually be reconstructed or more definitive male‑line relatives sampled, researchers might learn about physical traits, familial lineage, and even test speculative biological hypotheses about his perception or cognition. More immediately, verified genetic signatures could help authenticate disputed works and deter art fraud.

Next steps

Gonzalez‑Juarbe and collaborators say they hope this preprint will help secure permission to sample additional drawings and letters attributed to Leonardo. For now, the results are promising but preliminary: they highlight a possible family‑line signal consistent with Tuscany, while underscoring the methodological and interpretive limits of working with highly mixed, centuries‑old DNA.

Source: Preprint on BioRxiv; reporting by the Leonardo da Vinci DNA Project and interviews with the paper's authors.

Help us improve.