2025 brought major advances in our understanding of human evolution across about three million years. Key finds include new Ledi-Geraru teeth suggesting multiple archaic hominins in Ethiopia, Kenyan tools showing long-distance planning, and a confirmed 1.8-million-year-old Homo erectus jaw in Georgia. Proteomic and genomic work clarified Denisovan anatomy and traced a Denisovan gene into modern American populations, while multiple studies documented complex interbreeding and a recent rise of light pigmentation in Europe.

Ten Breakthrough Discoveries About Our Human Ancestors in 2025

2025 produced a string of important discoveries that sharpen our picture of human evolution across roughly three million years. New fossil, archaeological, genomic and paleoproteomic results revealed unexpected diversity among early hominins, earlier planning and dispersal behaviors, clearer Denisovan anatomy, surprising genetic legacies in modern populations, and complex episodes of interbreeding.

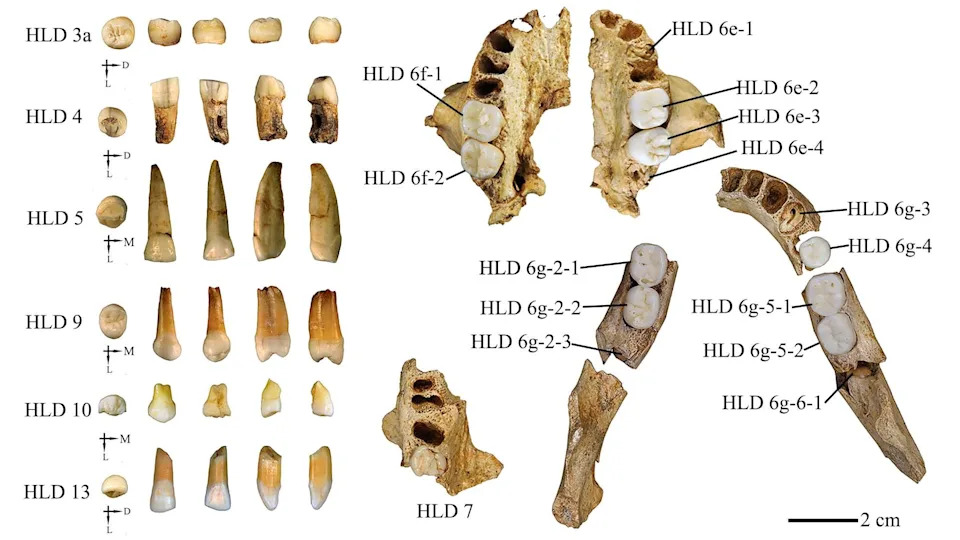

New Teeth From Ethiopia Reveal Multiple Contemporary Hominins

In August, researchers described 13 teeth from the Ledi-Geraru site in Ethiopia. Ten teeth dated to about 2.63 million years do not match known australopith species such as Australopithecus afarensis or A. garhi, suggesting a previously unrecognized lineage—provisionally called the Ledi-Geraru Australopithecus. Three additional teeth (about 2.59–2.78 million years old) appear to belong to the genus Homo, making them among the earliest specimens potentially attributable to our genus. Together, the finds imply at least three archaic hominin lineages lived in the region around 2.5 million years ago.

Early Planning: Long-Distance Transport of Toolstone in Kenya

Archaeologists examined more than 400 stone tools from Nyayanga (dated between 3.0 and 2.6 million years ago). Although the artifacts are simple flakes and were likely made by non-Homo toolmakers, the raw materials originate from sources more than six miles (≈9.7 km) away. This pattern indicates deliberate long-distance transport and forward planning by early hominins far earlier than previously documented.

Homo erectus in Eurasia: New Jawbone in Georgia

A 1.8-million-year-old jaw found at Orozmani, Georgia, confirmed earlier suggestions that Homo erectus reached the Caucasus soon after leaving Africa. Along with the Dmanisi site, these Georgian finds represent the earliest well-dated evidence of H. erectus outside Africa and attest to an early and rapid dispersal into Eurasia.

Oceania: Sulawesi Tools Push Hominins Into Island Southeast Asia Early

Stone tools on Sulawesi indicate hominin presence in parts of island Southeast Asia by roughly 1.5 million years ago. Without skeletal remains, researchers cannot yet identify the toolmakers definitively—candidates include H. erectus and possibly small-bodied island taxa such as H. floresiensis. Further excavation may clarify which species occupied Sulawesi.

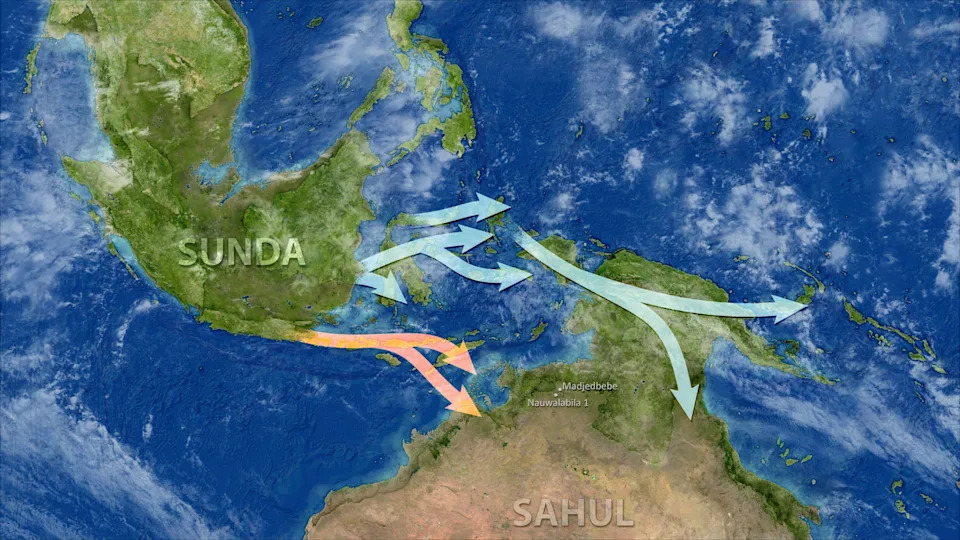

Peopling of Australia: Genomic Evidence Supports a ~60,000-Year Timeline

November genomic analyses support a "long chronology" for Australia, with modern humans arriving around 60,000 years ago, likely via at least two Western Pacific routes. This interpretation aligns with archaeological indicators (stone tools, cave pigments). However, a competing "short chronology" that places arrival closer to 50,000 years ago—based on other genetic patterns—remains debated.

Extinction of Homo floresiensis: Climate and Competition

Research from Flores suggests a substantial rainfall decline between ~76,000 and 61,000 years ago and the disappearance of the island's Stegodon population around 50,000 years ago. Reduced prey availability, environmental stress and potential competition with incoming modern humans likely contributed to the disappearance of the diminutive H. floresiensis by about 50,000 years ago.

Denisovans Come Into Focus: Proteins, DNA, and Cranial Finds

Paleoproteomic and genomic studies made Denisovans less enigmatic in 2025. A thick jawbone recovered off Taiwan in 2000 was identified as Denisovan, and ancient proteins from the so-called "Dragon Man" skull (discovered in China in 1933) point to a Denisovan affinity—though taxonomic questions (e.g., Homo longi) remain. A reconstructed ~1-million-year-old squashed skull from China has been proposed as a possible Denisovan ancestor. Together, these discoveries begin to map Denisovan anatomy and geographic spread.

Denisovan Genes in Modern People: The MUC19 Story

Genetic analyses revealed a Denisovan-like variant of the MUC19 gene in about one in three Mexicans today. The evidence suggests this Denisovan sequence entered modern human genomes indirectly: Denisovans transmitted it to Neanderthals during interbreeding, and Neanderthals later passed it to humans. This is a clear example of a Denisovan genetic legacy reaching present-day populations via Neanderthal intermediaries; its functional effects are still under investigation.

Complex Interbreeding and Cultural Interaction

2025 added several examples of hybridization and coexistence among hominin groups. A set of ~300,000-year-old teeth from China show a mix of archaic and modern traits that could indicate interbreeding between local Homo populations and H. erectus. Research from Israel suggests Neanderthals, modern humans and a third lineage shared caves around 130,000 years ago, possibly interacting for millennia. DNA linked to the Australian migration route further implies early modern humans likely interbred with one or more archaic island or Eurasian hominins.

Recent Appearance of Light Pigmentation in Europe

Analysis of 348 ancient genomes from Western Europe and Asia indicates that alleles associated with lighter skin, hair and eye color first appear around 14,000 years ago and became common in Europe only within the last few thousand years—widespread by about 1000 B.C. Until roughly 3,000 years ago, most Europeans likely retained darker pigmentation traits.

Takeaway: The combined fossil, archaeological and molecular advances of 2025 emphasize a more intricate and interconnected human past—one marked by multiple contemporaneous lineages, earlier planning and dispersal, ongoing interbreeding, and surprising genetic legacies that persist in people today.