A 2025 study in Scientific Reports finds two semiaquatic insects use different midleg designs to move on water. Rhagovelia distincta rows with a flexible, porous midleg fan that acts as a "leaky paddle," producing drag-based thrust. Gerris latiabdominis uses dense hydrophobic hairs to dimple and push against surface tension. Drag-based fans excel in flowing water, while surface-tension thrust is optimal in calm water; both inspire bio-inspired robot designs.

How Tiny Bugs Row, Skate and Sprint Across Water: Leaky Paddles and Surface-Tension Tricks

When we picture animals moving across water, we usually imagine birds landing or frogs leaping. But at a scale smaller than a pea, some insects don’t just walk on water — they row, skate and sprint across the surface using two very different mechanical tricks. A 2025 study in Scientific Reports reveals how distinct midleg adaptations let these tiny athletes generate thrust on a liquid interface that yields under force.

Two Strategies, One Problem

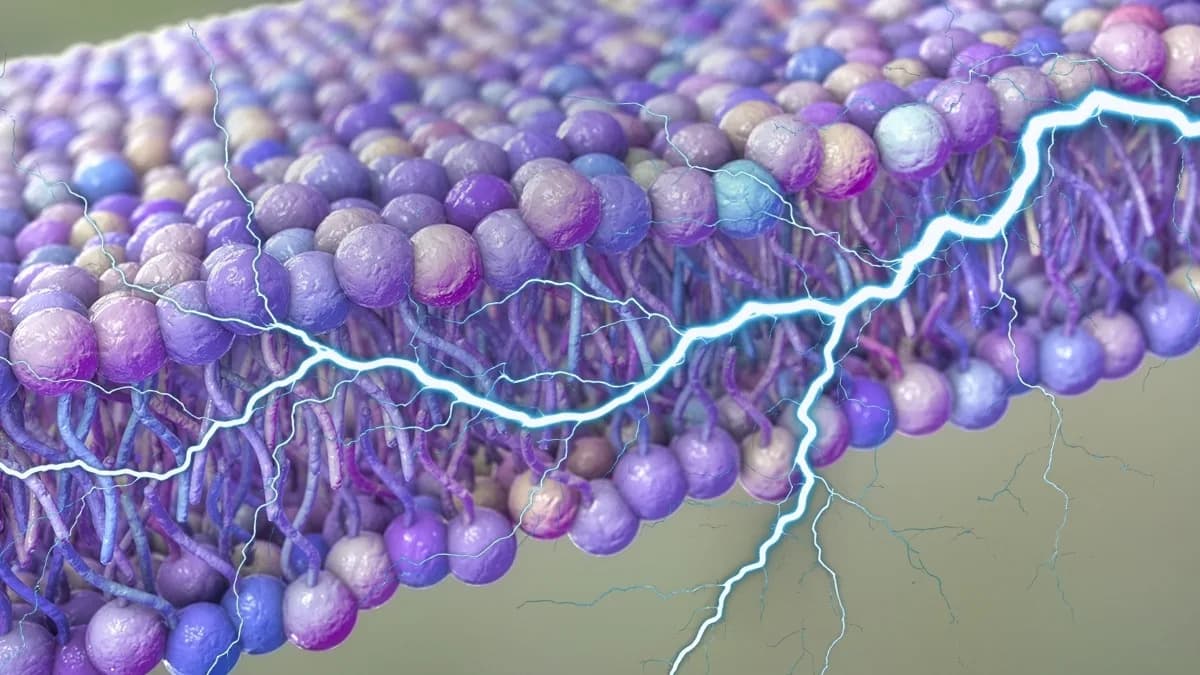

At the air–water boundary, molecules cling together, creating surface tension. For lightweight, hydrophobic insects, that surface acts like an elastic film they can sit on without sinking. But floating is only half the challenge: to move, an insect must push backward against the fluid to produce forward thrust. Researchers compared two semiaquatic species and found two mechanically and ecologically distinct solutions.

Leaky-Paddle Rowing: Rhagovelia distincta

Rhagovelia distincta (a ripple bug) uses a midleg fan formed by clusters of extended hair-like setae that, when splayed, act like a paddle blade. Unlike a solid oar, this fan is porous—tiny gaps let water flow through, so scientists call it a "leaky paddle." The fan increases contact area during each power stroke, allowing the insect to push enough water backward to move forward. The setae are flexible enough to open and close with each stroke yet stiff enough to impart meaningful drag-based thrust. Rapid, repeated strokes turn modest per-stroke forces into smooth forward motion.

Surface-Tension Dimpling: Gerris latiabdominis

Gerris latiabdominis (a water strider) lacks a fan but has densely packed hydrophobic setae that trap air and prevent wetting. Instead of displacing large volumes of water, these legs deform the surface into small dimples. Surface tension around those dimples produces reaction forces that are oriented rearward, giving thrust without breaking the water film. It’s similar to pressing and pushing on a trampoline: the elastic response of the surface returns an upward-and-forward force.

When Each Strategy Works Best

These two strategies are matched to different environments. Drag-based propulsion with leaky fans is especially effective in moving or turbulent water, where short, forceful strokes and increased fluid interaction help counter currents. Surface-tension thrust is most efficient in calm water, where preserving the surface film and exploiting its elastic behavior yields steady, low-penetration locomotion.

Bioinspired Engineering

Engineers are taking note. Flexible, leak-tolerant paddles and techniques that harness surface tension inspire new micro-robotic designs for traversing the air–water interface. Such bio-inspired devices could enable inspection, monitoring or exploration in environments where wheels or propellers are impractical.

Conclusion

Whether by pushing water backward with a porous midleg fan or by bending the surface with hydrophobic hairs, these insects solve a complex mechanical challenge with compact, elegant solutions. Their differing morphologies—setae spacing, stiffness and arrangement—map directly to performance in varied habitats, offering both evolutionary insight and practical blueprints for small-scale aquatic robotics.

Help us improve.