The mirror spider’s shifting reflective plates illustrate a widespread natural pattern: true tessellations—discrete geometric tiles separated by softer seams—appear across animals, plants, microbes and viruses. Researchers compiled about 100 examples in PNAS Nexus and developed a framework to compare tile composition, connections and functions. Independent evolution produced similar solutions (e.g., shark cartilage, chiton plates, insect eye facets) because geometry, growth constraints, and the need to balance stiffness and flexibility favor tiled architectures. The online catalogue aims to be a living reference to reveal tessellations across biology.

Why Life Repeats Geometric Tile Patterns: From Mirror Spiders to Shark Cartilage

The mirror spider can quickly rearrange a mosaic of tiny reflective plates beneath the outer layer of its abdomen, changing the pattern and timing of mirrorlike flashes. That striking display is one example of a widespread biological motif: discrete geometric tiles separated by softer seams—true tessellations—that recur across animals, plants, microbes and even viruses.

A Catalogue of Nature’s Tiles

Researchers compiled roughly 100 examples of these tiled architectures and published their catalogue in PNAS Nexus. Study co-author Mason Dean of City University of Hong Kong first noticed a regular tiled layout while examining micro–computed tomography scans of a ray’s skeleton; what looked like pixelated noise turned out to be a mosaic of hexagons and pentagons packed edge to edge across cartilage. Humboldt University zoologist Jana Ciecierska-Holmes found similarly interlocking plates on the outer coating of millet seeds when she began searching for more examples. Those observations motivated the team to ask: how widespread are such tessellated structures, and why do they keep appearing?

What Counts as a Tessellation?

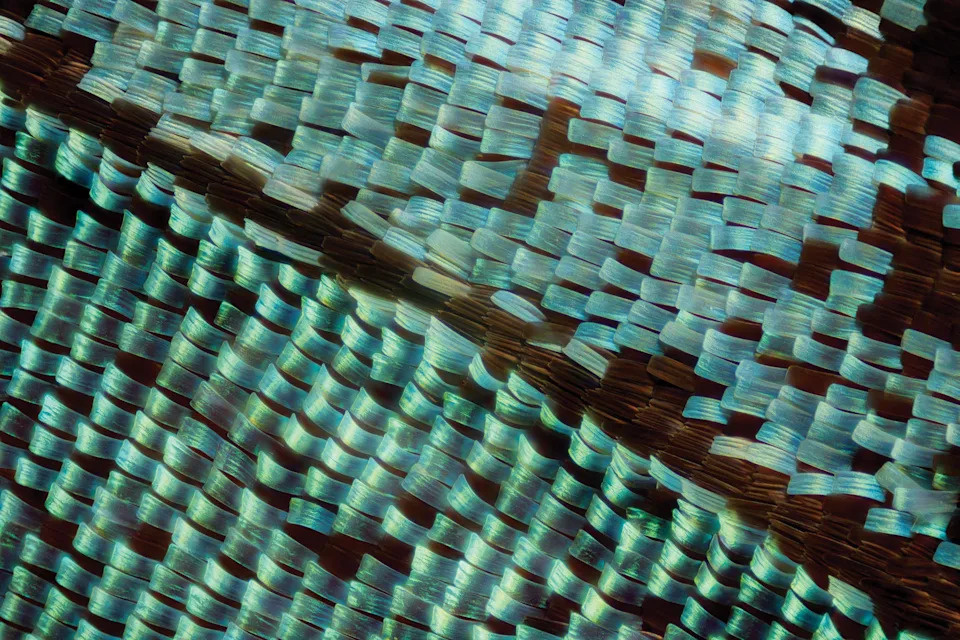

The team focused specifically on structural tessellations—where tiles are discrete physical pieces separated by softer seams—rather than on mere visual patterns (like coloration) or hollow regular structures such as honeycombs. To compare systems across very different organisms, they developed a framework describing what tiles are made of, their shapes, how they connect, and the functions they serve. This allowed the researchers to identify clear structural parallels across organisms that do not share recent common ancestry.

Concrete Examples

Independent evolutionary paths have produced similar tiled solutions for protection, movement, and sensing. Examples include:

- Chiton mollusks, which evolved articulated shell plates that act like overlapping tiles.

- Sharks and rays, whose tessellated cartilage commonly forms predominantly six-sided tiles that efficiently cover curved surfaces.

- Microscopic amoebae that build protective casings by assembling scavenged mineral tiles.

- Insect eyes, where tiled facets form compound lenses.

- Plant surfaces such as the elephant’s foot plant, which shows corklike plate patterns, and fruit peels that appear tiled.

- Butterfly wing scales and the bony plates of armadillo lizards, both using tiled layouts for coloration, protection, or flexibility.

Why Tiling Keeps Evolving

Geometry and growth constraints help explain the repeated emergence of tessellations. Hexagonal or six-sided tiles are an efficient way to cover curved surfaces with minimal gaps. Tile borders often line up with regions where new cells are added during growth, enabling tissues to expand while retaining structural function. Pairing rigid tiles with softer seams balances stiffness and flexibility—an arrangement that resists external forces yet allows movement and growth.

"Once you start paying attention to that, you see it everywhere," says Mason Dean. Co-author Jana Ciecierska-Holmes adds, "You kind of go into the tessellation world."

Practical Value of the Catalogue

The authors hope their online catalogue will be a living resource that helps researchers and naturalists recognize tessellations in the organisms and structures they study. By clarifying definitions and drawing structural parallels across kingdoms, the work opens pathways for comparative biology, biomimetic design, and engineered materials that mimic nature’s tiled solutions.

Source: PNAS Nexus; reporting and quotes from study co-authors Mason Dean and Jana Ciecierska-Holmes, with commentary from Stanislav Gorb (Kiel University).

Help us improve.