Researchers in 2025 identified 26 previously unknown bacterial species from samples collected in 2007 inside NASA cleanrooms used to assemble the Phoenix Mars Lander. Seventeen years of advancing genetic tools allowed scientists to map these genomes and reveal adaptations such as chemical resistance, enhanced DNA repair, and spore formation. Teams will soon expose the strains to a planetary simulation chamber that reproduces Mars-like conditions to test their survival, a finding with important implications for planetary protection policy.

26 Previously Unknown Bacteria Found in NASA Cleanrooms — Could They Survive a Trip to Mars?

In 2025, researchers announced the identification of 26 bacterial species never before classified — recovered from samples taken inside NASA cleanrooms used to assemble the Phoenix Mars Lander. The discovery is striking because these microbes were collected in 2007 from facilities designed to be near-sterile, raising new questions about how hardy terrestrial life can be and what that means for missions to other worlds.

How the Organisms Were Discovered

Teams swabbed surfaces in the Kennedy Space Center cleanroom during the 2007 assembly of the Phoenix lander. From those samples scientists isolated 215 distinct bacterial strains; 26 of those proved novel. Advances in genetic sequencing and analysis over the next 17 years made it possible to fully map these genomes and recognize them as previously unknown species.

"It was a genuine 'stop and re-check everything' moment," said study co-author Alexandre Rosado, reflecting on finding microbes inside spaces intended to be nearly sterile.

What Makes These Bacteria Remarkably Resilient

Genetic analysis suggests these species possess adaptations that help them tolerate unusually harsh environments. Key traits identified include:

- Chemical Resistance: Genes that confer tolerance to common sterilizing agents used in cleanrooms.

- Enhanced DNA Repair: Mechanisms that help fix radiation-induced DNA damage.

- Spore Formation: Ability to form long-lived, dormant spores that can survive extended periods without nutrients.

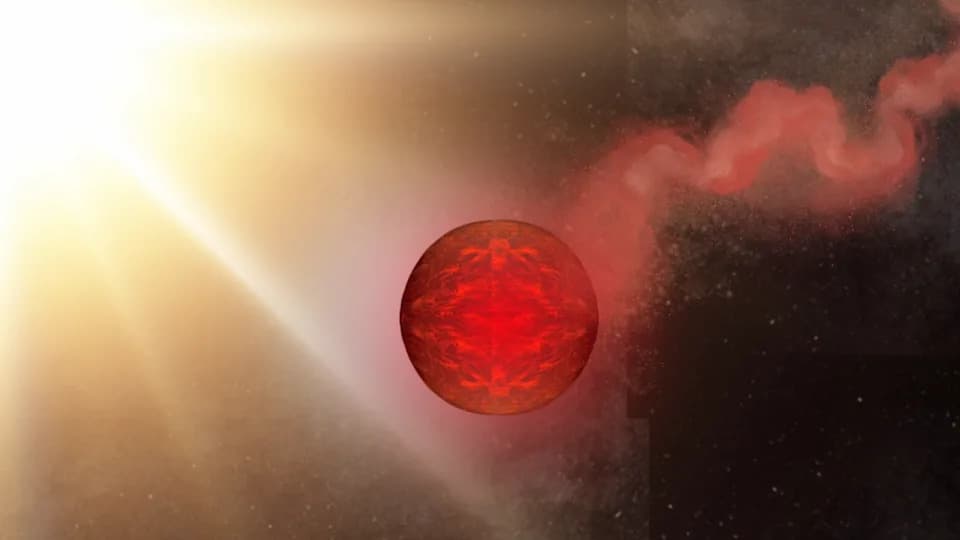

Together, these features raise the possibility that some strains could survive the stresses of space transit and remain viable under Martian surface conditions.

Next Steps: Mars-Like Testing and Planetary Protection

To test that possibility, the research team will expose selected strains to a planetary simulation chamber that reproduces Mars-like extremes — low temperatures, near-vacuum pressures, intense ultraviolet radiation, and elevated ionizing radiation levels. These experiments, expected to begin within months, will help define the microbes' survival limits and inform contamination risk assessments.

The finding carries direct implications for planetary protection policy: it underscores the need to refine sterilization protocols to prevent forward contamination of other worlds and to guard against accidental introduction of non-terrestrial organisms to Earth during sample return missions.

Bottom line: Microbes can persist in environments designed to exclude them. Understanding how and how long they survive will be essential to protecting both Earth and other planets as exploration advances.

Help us improve.