ISS experiments show microgravity removes gravity‑driven mixing and slows infections from ~20–30 minutes to more than four hours, forcing different evolutionary paths over a 23‑day selection period. T7 phages adapted by mutating receptor‑binding genes (gp7.3, gp11, gp12), while bacteria adjusted stress and nutrient systems. Space‑evolved phages were more effective against some antibiotic‑resistant uropathogenic E. coli, suggesting low‑mixing selection could help develop improved antibacterial therapies and inform medical planning for long space missions.

Space-Evolved Phages Show Promise Against Drug-Resistant Superbugs

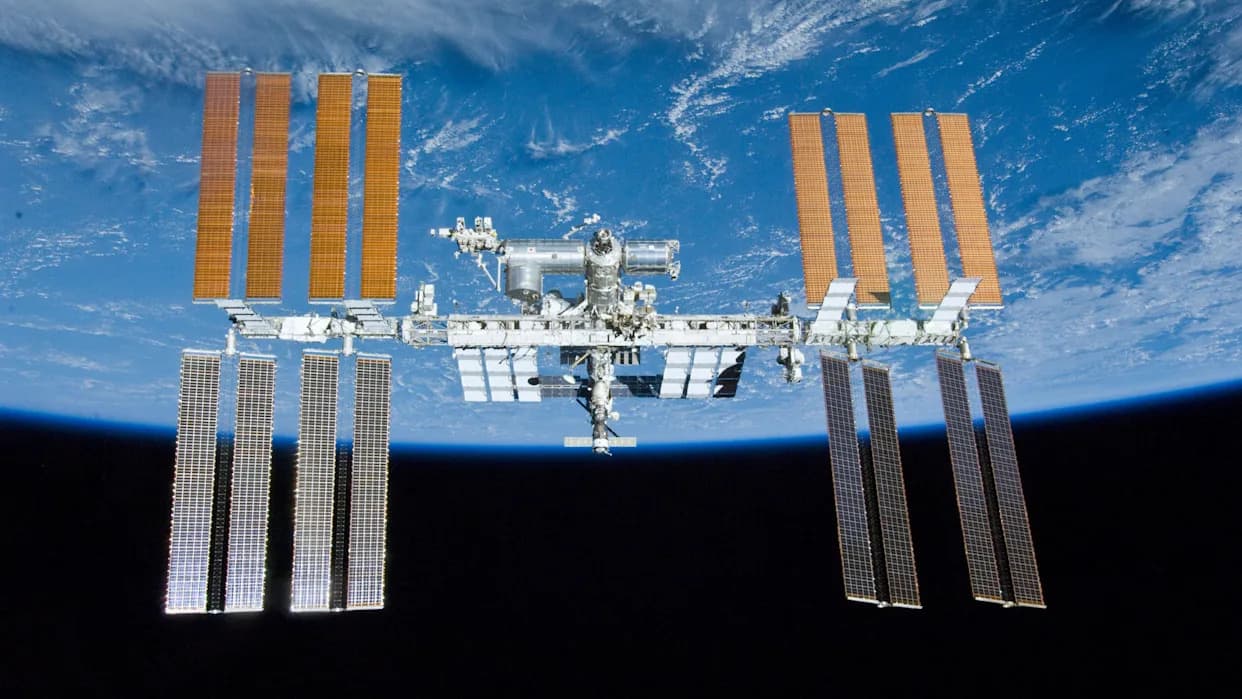

Researchers aboard the International Space Station report that microgravity fundamentally alters how bacteriophages and bacteria evolve, producing phage variants with enhanced ability to infect some antibiotic‑resistant pathogens.

On Earth, gravity-driven convection helps viruses encounter bacterial targets, so many productive infections develop in roughly 20–30 minutes. In microgravity that mixing disappears and microbes must rely on slow molecular diffusion—like waiting for sugar to dissolve in perfectly still coffee. In the ISS experiments, infections that normally take minutes on Earth stretched to more than four hours in space.

That prolonged encounter time reshaped the selective landscape. Over an extended 23‑day selection period, T7 bacteriophages and their bacterial hosts followed evolutionary routes not seen under terrestrial conditions. The phages adapted by improving receptor binding; genes associated with attachment—gp7.3, gp11 and gp12—accumulated mutations faster than in Earth controls. Bacteria countered by altering stress‑response pathways and nutrient‑transport systems.

Genetics and Functional Tests

Deep genetic analysis confirmed that space‑evolved variants diverged from Earth controls. Notably, phage isolates that thrived in orbit often performed poorly back on Earth, and Earth‑evolved phages showed no advantage in microgravity conditions—evidence of environment‑specific adaptation rather than universal fitness gains.

When tested against uropathogenic Escherichia coli (a common cause of stubborn urinary tract infections), several space‑adapted T7 variants produced larger infection zones and higher killing efficiency against antibiotic‑resistant strains that wild‑type T7 phages typically struggle to control. "This was a serendipitous finding," said study lead Srivatsan Raman of the University of Wisconsin–Madison.

Implications and Next Steps

The results suggest two practical pathways: first, using controlled low‑mixing laboratory systems on Earth to mimic key microgravity effects and select for therapeutic phage properties without expensive spaceflight; second, guiding medical preparedness for long‑duration missions (for example, to Mars), where microbes could evolve under constrained mixing. The authors caution that any therapeutic use will require thorough safety, host‑range and efficacy testing before clinical application.

Published In: PLOS Biology.

Lead Researcher: Srivatsan Raman, University of Wisconsin–Madison.

Help us improve.