The University of Wisconsin–Madison compared T7 bacteriophage–E. coli interactions aboard the ISS and on Earth and found that microgravity delayed early infection onset (1–4 hours) but allowed infection to proceed over longer periods (23 days). Genomic analyses revealed microgravity‑specific phage mutations—many in structural and host‑interaction genes—and a distinct selection landscape identified by deep mutational scanning. Some space‑enriched phage variants were synthesized and killed uropathogenic, T7‑resistant E. coli in lab tests, suggesting therapeutic potential while also raising biosafety concerns for spacecraft microbiomes.

Microgravity Slows Phage Infections and Redirects Viral Evolution Aboard the ISS — Space‑Derived Phages Kill Drug‑Resistant E. coli

The International Space Station (ISS) is a closed habitat where microbes can behave very differently than they do on Earth. A University of Wisconsin–Madison team studied how microgravity affects bacteriophages (viruses that infect bacteria) and their host Escherichia coli by running matched experiments on the ISS and in terrestrial controls. Their results, published in PLOS Biology, show that microgravity can delay infection timing, change evolutionary trajectories for both phage and bacteria, and reveal viral variants with potential therapeutic value.

Methods

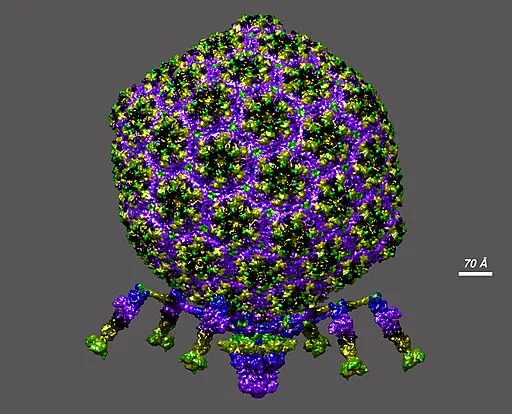

The researchers focused on the well‑characterized T7 bacteriophage and E. coli. They prepared sealed, unshaken sample tubes with identical mixtures at varying starting ratios of phage to bacteria. One set of tubes flew to the ISS in 2020 aboard Northrop Grumman’s NG‑13 Cygnus; the matched control set remained on Earth. Short‑term incubations were sampled at 1, 2 and 4 hours, and a long‑term run extended to 23 days. Because on‑orbit and ground procedures cannot always run in perfect parallel, the team recorded exact on‑orbit timings and matched them afterward on Earth.

Key Findings

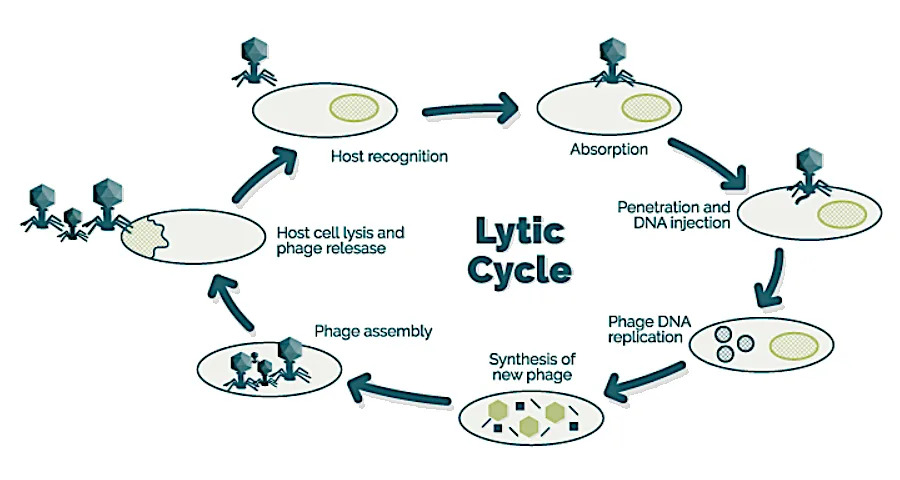

Under typical lab conditions on Earth, T7 can complete an infection cycle in well under an hour. In the sealed, no‑shake conditions designed to mimic microgravity, however, infection dynamics were slower. Ground controls showed a surge in productive infections between two and four hours; the ISS samples did not exhibit a comparable early surge. After 23 days in orbit, infection had proceeded and E. coli counts were reduced, indicating that phage infection can still occur in microgravity but on a different timescale.

"We hypothesize that reduced fluid mixing in microgravity, because there's no gravity‑driven convection, lowers the encounter rate between phage and bacteria, and that microgravity‑induced stress on the host may alter receptor expression or intracellular processes, further slowing productive infection," said Dr. Phil Huss, a lead author.

Genomic analysis after 23 days revealed mutations across phage genomes, with a microgravity‑specific enrichment in genes related to capsid structure and host interactions. The team used deep mutational scanning to map more than 1,600 phage variants and found that the variants favored in microgravity differed sharply from those selected on Earth. Several microgravity‑enriched phage mutants were synthesized and tested against uropathogenic E. coli (strains associated with urinary tract infections) that were resistant to standard T7 infection; some of these engineered phages killed the resistant bacteria in laboratory tests.

Bacteria also evolved: E. coli exposed to phage pressure accumulated more mutations than unchallenged controls, with notable changes in outer membrane genes likely to affect phage attachment and stress tolerance. Together, these results indicate that microgravity is a distinct selection environment that reshapes which viral and bacterial mutations matter for survival and infection.

Implications and Next Steps

The study carries two major implications. First, microgravity can be a tool to explore novel evolutionary solutions that might be harnessed for phage therapy or microbiome engineering on Earth. Second, microbes aboard spacecraft may adapt in unexpected ways that could affect astronaut health, for example by altering virulence or antibiotic susceptibility. The authors emphasize the need for longer, more comprehensive experiments to monitor antibiotic resistance, stress responses, and competitive interactions over time.

"The real power of these space‑derived fitness landscapes is that they can be merged with the rich terrestrial datasets we already have to sharpen engineering strategies for therapeutic use cases," Huss said.

Practical challenges remain: ISS experiments require extensive planning, strict biosafety testing, and logistical coordination. Nevertheless, the study demonstrates that microgravity not only slows infection kinetics but also qualitatively reshapes phage–host coevolution — offering both biosafety concerns for long‑duration missions and actionable leads for developing better phage therapeutics on Earth.

Help us improve.