JWST has discovered very massive black holes in galaxies that existed when the universe was under a billion years old — a timing that challenges conventional growth models. New high-resolution simulations by a team at Maynooth University indicate that short-lived super-Eddington accretion episodes could let stellar-remnant "light seeds" grow quickly to tens of thousands of solar masses. That early growth would give them a head start for later mergers and accretion to produce the supermassive black holes JWST finds. The team suggests space-based gravitational-wave observatories such as LISA could detect the mergers that confirm this scenario.

Early Black Holes' 'Feeding Frenzy' May Explain JWST's Cosmic Puzzle

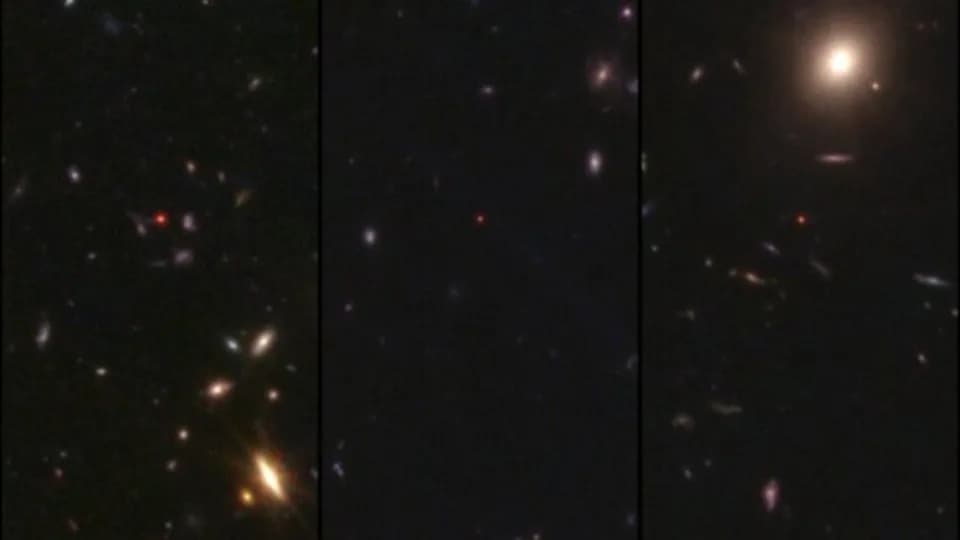

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) has uncovered unexpectedly massive black holes in the infant universe — some appearing less than a billion years after the Big Bang. A new study led by Daxal Mehta and John Regan of Maynooth University suggests brief episodes of runaway accretion, a black hole "feeding frenzy," could explain how small early black holes grew rapidly enough to become the seeds of the supermassive monsters JWST sees.

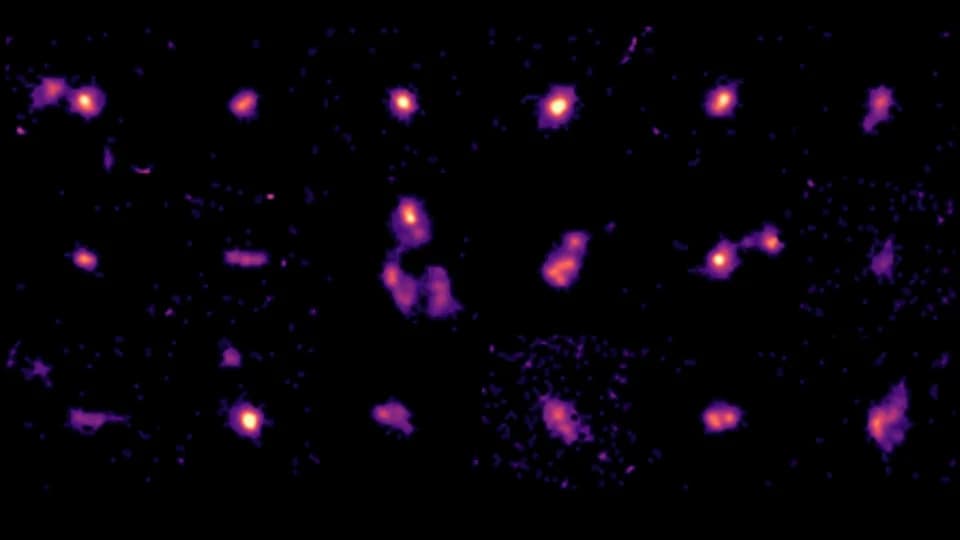

Simulating the Turbulent Early Cosmos

The research team used high-resolution computer simulations to model the dense, chaotic gas flows inside the universe's first galaxies. Their simulations show that the extreme, turbulent conditions prevalent a few hundred million years after the Big Bang could drive short-lived phases of super-Eddington accretion — when a black hole consumes matter faster than the classical Eddington limit would normally allow.

What Is the Eddington Limit?

The Eddington limit defines the balance between inward gravitational pull and outward radiation pressure created by accretion. If accretion produces too much radiation, that radiation pushes gas away and chokes off further growth. But in highly dense, chaotic environments the simulations reveal, pockets of gas can funnel onto a black hole so efficiently that the object temporarily outpaces that limit and experiences rapid mass gain.

From Light Seeds To Giants

Black holes born from normal stellar collapse — known as "light seeds" with masses of tens to a few hundred solar masses — were long thought to be too small to become the billion-solar-mass objects JWST finds so early. Mehta and colleagues show these stellar-remnant black holes could, during brief super-Eddington phases, swell to tens of thousands of solar masses. That accelerated growth would provide a substantial head start, making later mergers and continued accretion capable of producing the supermassive black holes seen in very young galaxies.

"We found that the chaotic conditions that existed in the early universe triggered early, smaller black holes to grow into the super-massive black holes we see later, following a feeding frenzy which devoured material all around them," said Daxal Mehta. "These early black holes, while small, are capable of growing spectacularly fast, given the right conditions."

Team member John Regan added, "Heavy seeds are somewhat more exotic and may need rare conditions to form. Our simulations show that garden-variety stellar-mass black holes can grow at extreme rates in the early universe."

Observational Tests And Future Prospects

Direct electromagnetic confirmation of short-lived super-Eddington phases will be challenging. However, the merger history implied by rapid early growth could leave an imprint in the form of gravitational waves. The team points to the Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (LISA), a planned ESA/NASA space-based gravitational-wave observatory targeted for launch in the mid-2030s, as a promising instrument to detect mergers of these early, rapidly growing black holes.

The study was published on Jan. 21 in Nature Astronomy.

Help us improve.