Summary: The article revisits the madman theory—the notion that projecting irrationality can coerce rivals—and argues it is far less effective today than during the Cold War. Key enabling conditions then—information scarcity, stable adversaries with shared risk norms, and exceptional credibility—have largely disappeared. In a 24/7 media environment and against actors accustomed to volatility, erratic signaling often becomes noise or invites probing. Targeted strategic ambiguity (for example, toward Taiwan) can still deter, but untethered unpredictability rarely produces durable leverage.

The 'Madman Theory' Revisited: Why Unpredictability Loses Its Bite in Modern Foreign Policy

Tariffs can appear and vanish overnight; military options are floated one day and declared off-limits the next. Erratic behaviour and deliberate unpredictability have recently been embraced by some as a foreign policy tool rather than a liability. But does the so‑called "madman theory" still work?

What Is the Madman Theory?

The madman theory is the idea that a leader who projects willingness to take extreme, seemingly irrational actions can reshape an adversary’s calculations by increasing the perceived risk of escalation. Cold War thinkers such as Daniel Ellsberg and Thomas Schelling described how such signaling might deter or coerce rivals. Though originally used to explain behaviour, leaders have sometimes adopted it prescriptively as a bargaining tactic.

Why It Worked (Sometimes) During the Cold War

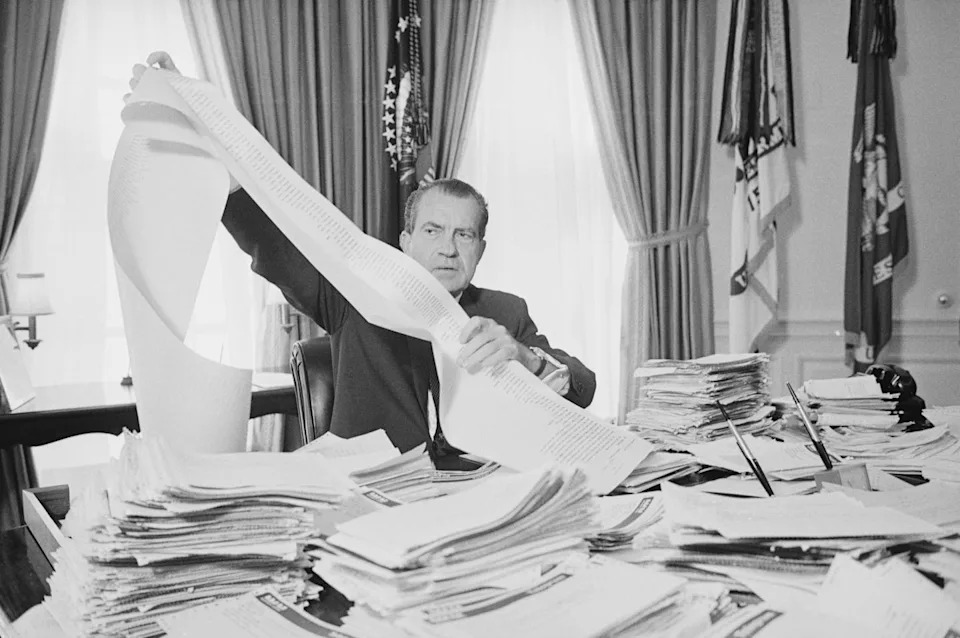

Scholars and historians link the theory most closely with President Richard Nixon, whose 1969 move to place U.S. forces on heightened alert is often cited as having increased Soviet caution during the Vietnam era. That era supported the tactic because of three background conditions:

- Information Scarcity. Signals moved slowly through narrow, professional channels—diplomats, intelligence officers and military staff filtered messages—so ambiguity could be sustained.

- Stable, Risk‑Averse Adversaries. Soviet decision‑makers operated in a hierarchical system that prized caution; they feared miscalculation that could imperil the state or their positions.

- Credibility Through Restraint. The madman posture was exceptional against a backdrop of institutional order, making apparent erraticism more persuasive.

Why the Strategy Is Weaker Today

Those conditions no longer hold. Real‑time media and social platforms mean threats are tweeted, clipped and dissected instantly; ambiguity rarely has time to crystallise into public fear and often dissolves into noise. Many contemporary rivals—Russia, China and Iran among them—already operate in turbulent environments and are less likely to be frozen by volatility. Instead, apparent irrationality can invite probing, hedging, or reciprocal escalation.

Moreover, unpredictability has become commonplace in some capitals. When leaders repeatedly bluster, contradict themselves and retreat without extracting concessions, they make unpredictability itself predictable. That pattern erodes the tactic’s coercive power rather than enhancing it.

Illustrative Cases

Two recent examples highlight the limits of the approach. In dealings with Iran, pressure and the threat or use of strikes have occurred without clear boundaries for escalation—creating uncertainty rather than durable leverage. The episode over Greenland, in which coercive rhetoric was directed at an ally, mainly strained relations within NATO and did not secure the intended outcome.

Where Ambiguity Still Helps

Not all ambiguity is ineffective. Targeted uncertainty about specific responses can sustain deterrence by keeping adversaries cautious. U.S. strategic ambiguity toward Taiwan, for example, helps prevent either side from locking into automatic escalation by leaving Washington’s military response intentionally unclear. The lesson is that ambiguity can work when it is tethered to clear objectives and visible limits.

Conclusion

The madman theory was devised for a more rigid, rule‑bound international order. In today’s fast, public and fragmented information environment—and against opponents who expect volatility—untethered unpredictability rarely produces lasting leverage. Strategic ambiguity confined to defined goals and constraints remains useful, but volatility for its own sake is more likely to generate confusion, hedging and escalation than compliance.

Originally published by The Conversation. Written by Andrew Latham, Macalester College. The author discloses no relevant affiliations beyond his academic appointment.

Help us improve.