Researchers propose using honeybees as a terrestrial model for alien intelligence to test whether mathematics might serve as a universal language for interstellar communication. Experiments from 2016 to 2024 show bees can perform simple addition and subtraction, recognize zero, and map symbols to numbers. Historical efforts (Voyager, Arecibo) already favor numbers as a bridge to unknown minds. While math is a promising foundation, differing species may develop distinct mathematical "dialects," so interstellar messaging should prioritize simple, robust patterns.

Bees as a Model for Alien Intelligence: Can Mathematics Be a Universal Language for Interstellar Communication?

Humans have long wondered whether we are alone in the universe and, if not, how we might communicate with intelligent life whose minds and senses are radically different from our own. Given the vast distances between stars — our nearest stellar neighbor is about 4.4 light-years away — two-way contact would likely take decades. That makes designing reliable long-distance signals and shared foundations for meaning a priority for any attempt at first contact.

Why Mathematics?

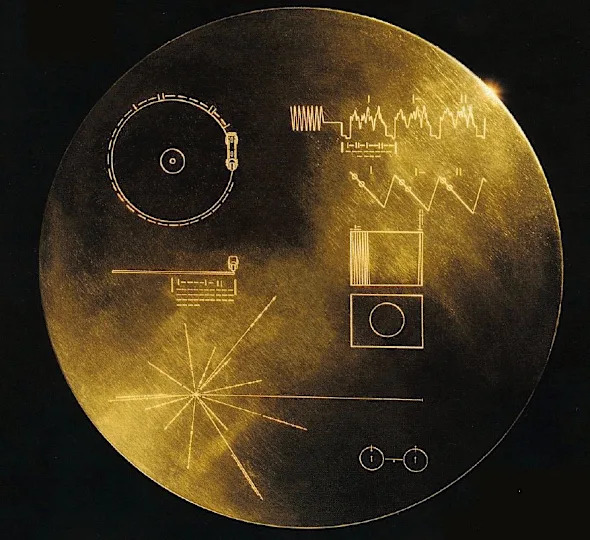

Mathematics is often proposed as a neutral, potentially universal basis for communication. The idea is centuries old: Galileo described the universe as a book "written in the language of mathematics." Popular culture and scientific outreach have reinforced the concept — from the prime-number pulses in Carl Sagan's Contact to the Voyager Golden Records and the binary Arecibo message. Those examples show a practical preference for numbers and basic physical constants when addressing unknown intelligences.

Bees: A Terrestrial 'Alien' Model

A creature with two antennae, six legs, and five eyes may sound alien, but that description fits a honeybee. Bees and humans diverged more than 600 million years ago and possess dramatically different brain sizes and architectures. Yet both species exhibit social organization, complex communication, and some capacity for numerical reasoning.

The honeybee waggle dance is a sophisticated, nonverbal code that signals direction, distance, angle relative to the sun, and resource quality. Because bees are so evolutionarily distant from us and process information differently, they serve as a useful terrestrial analogue for imagining how an "insectoid" intelligence might think and communicate.

What the Experiments Show

Between 2016 and 2024, our team ran outdoor experiments with freely flying honeybees that voluntarily returned to participate in simple arithmetic tasks in exchange for sugar-water rewards. Across studies, bees demonstrated several surprising abilities:

- Solving simple addition and subtraction tasks (typically adding or subtracting one)

- Categorizing quantities as odd or even

- Ordering sets of items by size or number

- Showing an understanding of the absence of quantity (a rudimentary grasp of zero)

- Associating abstract symbols with numerical values, a basic form of symbolic numeracy

These results indicate that tiny brains can implement cognitive strategies for dealing with number and quantity. Learning to add or subtract by one provides a conceptual stepping-stone toward representing the natural numbers and building more complex numerical concepts.

Implications for Interstellar Communication

If distantly related species on Earth—humans and bees—can develop representations of number, then it strengthens the argument that mathematics might emerge independently wherever sufficiently sophisticated information-processing systems evolve. That could make mathematical structures a promising starting point for designing messages intended for unknown intelligences.

However, several caveats remain important:

- Different species may develop distinct mathematical frameworks or emphases — "dialects" shaped by their sensory modalities, ecological niches, or neural architectures.

- What counts as a meaningful mathematical concept may vary; simple operations or counts may be more reliably shared than higher-level abstractions.

- Transmitting mathematics requires careful encoding (e.g., binary patterns, physical constants, or action-based demonstrations) and patience because of long delays in interstellar exchange.

Conclusion

Using bees as a thought experiment and experimental subject highlights that numerical cognition need not depend on human-like brains. While math offers a promising foundation for cross-species or cross-civilization communication, designers of interstellar messages should expect variation in representation and look for robust, low-level commonalities (counts, simple operations, geometric relations, physical constants) as the most likely shared ground.

Bottom line: Bees strengthen the case that mathematics could be an emergent property of intelligence, but practical interstellar messaging must allow for different "mathematical dialects" and ground messages in simple, testable patterns.

Help us improve.