The search for extraterrestrial life is moving from speculation to observation by analysing exoplanet atmospheres for molecular 'barcodes' imprinted on starlight. Transmission spectroscopy during transits has already revealed molecules such as methane, carbon dioxide and water, but claims like the 2025 dimethyl sulphide detection on K2-18b underline the need for caution and reproducibility. Upcoming missions—ESA's Plato and Ariel and NASA's Roman and the planned Habitable Worlds Observatory—will greatly expand our ability to characterise potentially habitable worlds and look for biosignatures such as oxygen and the vegetation red edge.

How Astronomers Read Exoplanet Atmospheres to Search for Alien Life

We are in an era when questions that have long fascinated humanity are finally becoming testable. One of the most profound asks whether Earth is unique in supporting life.

Reading Atmospheric 'Barcodes'

A powerful way to search for life beyond our planet is to study the gases in exoplanet atmospheres. Quantum physics gives each molecule a distinctive, barcode-like pattern in light. When starlight passes through or is reflected by an atmosphere, these spectral fingerprints appear as absorption or emission features that telescopes can measure.

How Observations Work

The technique called transmission spectroscopy is most effective when a planet transits its star, so starlight filters through the thin limb of the atmosphere and lets us read its composition. The strength of a spectral feature depends on two things: the molecule's abundance and the intrinsic strength of its spectral lines. That is why some abundant gases can be hard to detect while some rarer gases are relatively easy to spot.

What We Can Detect Today

The James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) observes primarily in the infrared and has already measured atmospheric signatures on a variety of exoplanets. Robust detections of simple molecules such as methane, carbon dioxide and water vapor have been reported, although analyses can differ because teams sometimes make different choices when reducing and modelling the same data.

Controversy and Caution: The K2-18b Case

In 2025 a bold claim was made for dimethyl sulphide (DMS) in the atmosphere of the sub-Neptune K2-18b. On Earth, DMS is produced by marine phytoplankton and breaks down quickly in sunlit seawater, so its presence on an ocean world would be intriguing. Subsequent reanalyses, however, showed that the result depends strongly on which molecular fingerprints are included in the fit, and alternative explanations can match the observations just as well. The episode highlights both the promise of atmospheric biosignatures and the need for careful, reproducible analysis.

Why Rocky Earth Twins Are Harder

Detecting atmospheres around true Earth-sized rocky planets is significantly more challenging because their spectral signals are much fainter. JWST can push into this regime for a few favorable targets, but systematic limitations and noise make robust detections difficult with current capabilities.

The Next Generation Of Missions

The coming decade will bring dedicated observatories and new techniques that dramatically expand our reach:

- ESA Plato (planned 2026) will find more temperate, Earth-size planets around bright nearby stars that are well suited to follow-up spectroscopy.

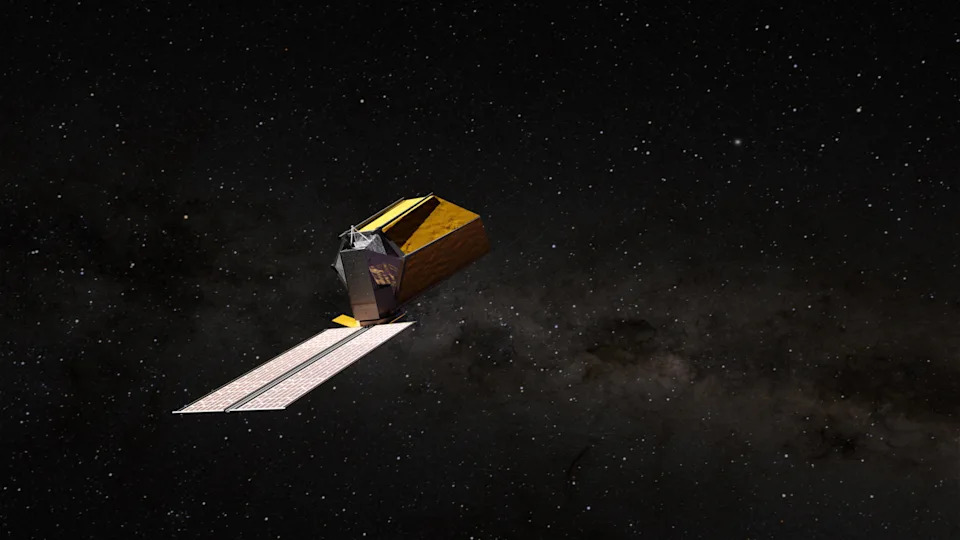

- NASA Nancy Grace Roman Space Telescope (planned 2029) will demonstrate coronagraph technology to suppress starlight and enable direct imaging of faint planets around nearby stars.

- ESA Ariel (planned 2029) is a mission dedicated to transmission spectroscopy across a large sample of exoplanets, designed to characterise atmospheric compositions in a systematic way.

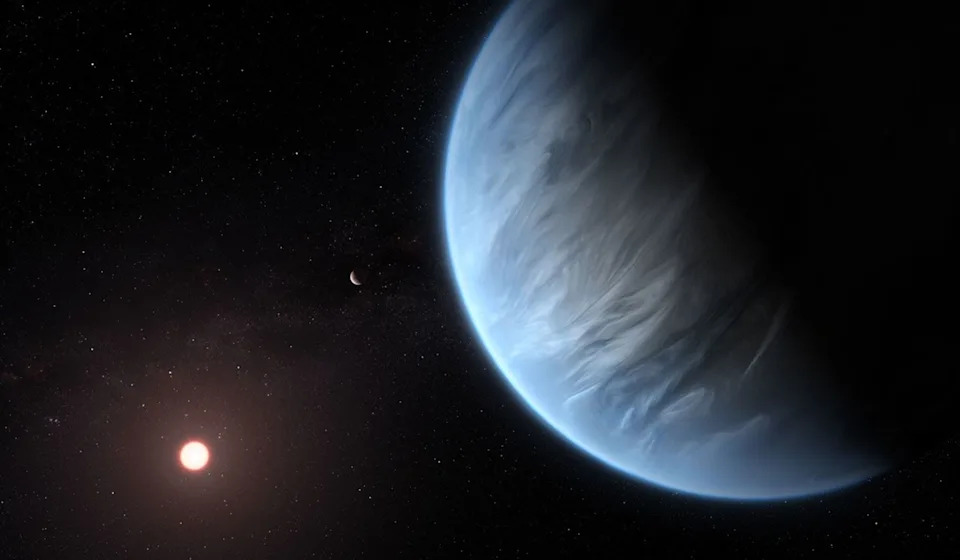

- Habitable Worlds Observatory (HWO, in planning) aims to use a high-performance coronagraph to study roughly two dozen Earth-like worlds. HWO would cover ultraviolet through near-infrared wavelengths, search for oxygen and other habitability indicators, and may even detect a 'vegetation red edge' from photosynthetic life.

Beyond Molecules: Mapping Surfaces

For nearby reflected-light targets, repeated observations can reveal changes due to a planet's rotation. Because land and ocean reflect differently, these variations can be used to build low-resolution maps showing continents and seas, offering further clues to habitability.

Conclusion

Detecting life beyond Earth remains difficult but is becoming increasingly realistic. Current observations have proven the methods and exposed pitfalls, while upcoming telescopes and instruments will expand the number and quality of targets. With careful analysis and better data, astronomers may soon be able to put firmer answers on whether Earth is unique in hosting life.

Help us improve.