The most complete Homo habilis skeleton yet found—excavated from Kenya’s Lake Turkana Basin—shows a humanlike skull paired with a primitive, ape-like upper body. Published Jan. 13 in the Anatomical Record, the study finds H. habilis had long, powerful arms and a small body (perhaps smaller than Lucy). Dental finds from 2012 anchored the identification, but limited lower-body remains mean questions about gait and bipedalism remain open.

Most Complete Homo habilis Skeleton Reveals Unexpectedly Primitive Body

A remarkably complete skeleton discovered in the Lake Turkana Basin of northern Kenya is the most comprehensive set of remains yet attributed to Homo habilis, one of the earliest members of our genus that lived more than two million years ago. While the skull retains humanlike features—such as a relatively large braincase and a flatter face—the newly analyzed postcranial bones suggest H. habilis retained many primitive, ape-like features in its body.

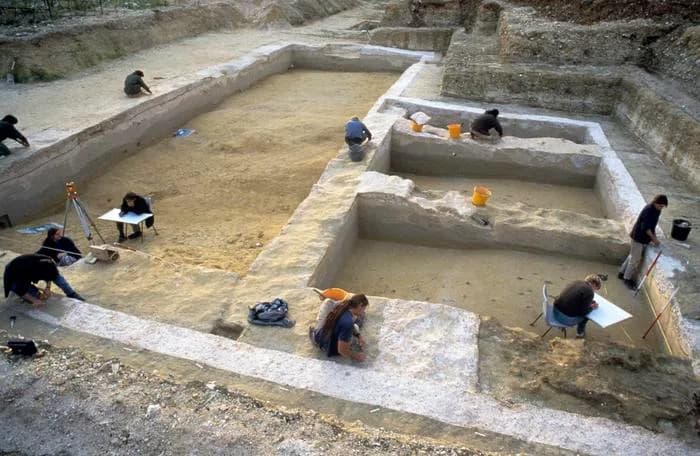

Discovery and Excavation

The find began in 2012 when Arbollo Aike of the Koobi Fora Research Project recovered some of the specimen’s teeth from Lake Turkana sediments. Over the next few years, researchers followed a scatter of bone fragments down a slope and uncovered additional teeth and a sequence of larger upper-body bones. The fully excavated material includes an almost complete lower dentition, both clavicles, complete humeri and forearm bones, and fragments of the scapulae and pelvis.

Decade-Long Analysis

It took more than a decade to analyze the material and to confirm that the bones belong to a single individual and to H. habilis. Study co-authors Ashley Hammond and Carrie Mongle emphasize that the teeth—often the most diagnostic elements for early hominins—were crucial for establishing the specimen’s identity. The research was published on January 13 in the journal Anatomical Record.

What the Bones Reveal

The new analysis corroborates prior suggestions that H. habilis combined a relatively humanlike cranium with a markedly primitive upper body. The arms were long and robust with proportions more similar to those of apes than to modern humans, suggesting retained climbing adaptations or a different locomotor repertoire. Overall body size appears to have been small—possibly smaller than the famous 3.2-million-year-old Australopithecus specimen "Lucy."

Although a pelvic fragment hints that H. habilis may have been capable of a more upright gait than earlier hominins, the lower-body remains are still too limited to settle precisely how modern its walking posture was. More fossils from the lower limbs would be needed to clarify where H. habilis fits in the evolution of humanlike bipedalism.

Significance

Because H. habilis is among the earliest members of the Homo genus, understanding its mix of primitive and derived traits helps illuminate the evolutionary steps that led to later Homo species, including our own. "A finding like this does give hope," says William Harcourt-Smith of the American Museum of Natural History, recognizing how rare and fragmentary H. habilis fossils have been. Rebecca Wragg Sykes (University of Cambridge and University of Liverpool) adds that even a few new fragments can transform interpretations of a species and its evolutionary context.

Bottom line: This unusually complete H. habilis individual underscores that early Homo combined a more humanlike skull with a body that retained many ancestral, ape-like features—complicating simple narratives of a linear march toward modern human anatomy.

Help us improve.