Stanford scientists report the discovery of tiny, rod-shaped RNA particles called obelisk in human mouths and guts. These viroid-like entities are smaller than typical viruses, carry circular single-stranded RNA genomes, and sometimes include one or two genes. Researchers found nearly 30,000 distinct types worldwide and now aim to learn how they replicate, which hosts they use, and whether they affect human health.

Scientists Find Tiny Rod-Shaped 'Obelisk' RNA Entities Living in Human Mouths and Guts

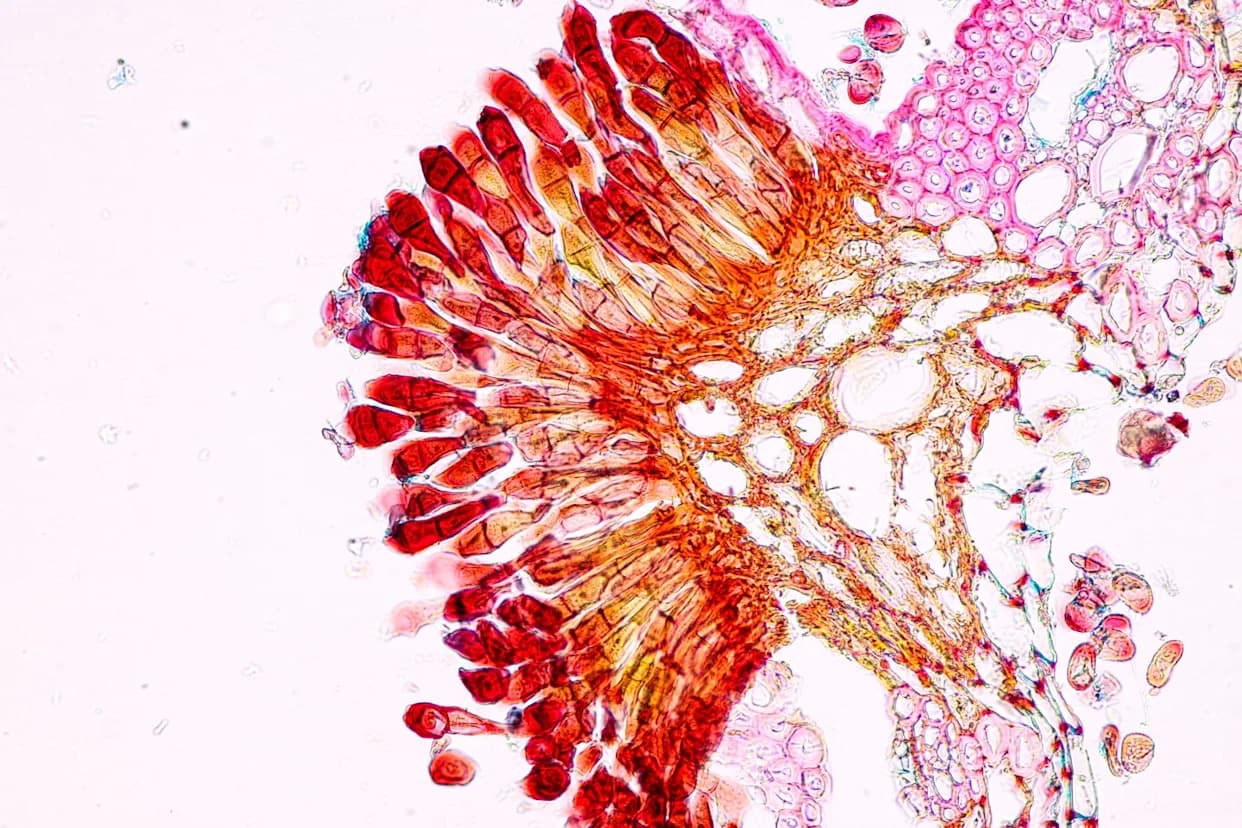

Stanford University researchers have reported the discovery of previously unknown, microscopic RNA particles living in human mouths and intestines. These rod-shaped entities — nicknamed obelisk by the team — are smaller than typical viruses, carry circular single-stranded RNA genomes, and in some cases contain one or two genes that may encode proteins.

The findings were described in a preprint from the Stanford group and summarized in subsequent coverage and commentary. The researchers called the particles “wildly weird” and have proposed the formal name obelisk because of their elongated, obelisk-like shape.

How obelisks fit into known biology

Microbiologist Ed Feil of the University of Bath explained these entities as “circular bits of genetic material that contain one or two genes and self-organize into a rod-like shape.” That combination places obelisks between viroids and viruses. Like viroids, obelisks appear to be small, circular, single-stranded RNA molecules without a protective protein coat. Unlike classic viroids, however, some obelisk genomes contain sequences predicted to code for proteins — a trait usually associated with viruses.

Viroids are extremely simple infectious agents known mostly from plants; they are short RNA molecules that cannot encode proteins but can replicate and sometimes cause disease. Obelisks are described as “viroid-like” because they share structural simplicity, yet they may be biologically distinct due to the presence of gene-like sequences.

What the team found

The Stanford analysis uncovered nearly 30,000 distinct obelisk types across diverse human populations. Most detections came from oral samples, though some obelisks were also found in gut microbiome data. The widespread presence suggests these RNA elements are common components of the human microbiome, at least in the sampled datasets.

Open questions and next steps

Key unknowns now include which host cells or microorganisms obelisks depend on to replicate, whether bacteria or fungi help them function, and whether they are harmless, beneficial, or harmful to humans. Researchers will need laboratory experiments to determine whether obelisks can replicate independently or require helper organisms, what proteins (if any) their genes produce, and whether they influence human health.

Why it matters

The discovery expands our view of the human microbiome and highlights how much biological diversity remains unseen. Whether obelisks represent a new class of infectious agent, a neutral component of microbial ecosystems, or something with clinical relevance is an open and intriguing question.

“The more we look, the more crazy things we see,” said Mark Peifer, a cell and developmental biologist at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, summarizing how much remains to be discovered in the microscopic world.

Note: These results come from sequence data and a preprint; peer-reviewed experiments and functional validation will be required to confirm how obelisks behave biologically.

Help us improve.