The Bishop Henry Whipple Federal Building — located near Fort Snelling and the Bdote — has become a flashpoint as intensified immigration enforcement and the January 7 fatal shooting of Renee Good spurred protests and community response. Bishop Whipple’s 19th-century advocacy for Native people continues to inspire local faith and Indigenous leaders, even as his paternalistic support for assimilation and boarding schools complicates his legacy. Campaigns that began in 2019 to remove his name have evolved into direct aid, legal support and monthly vigils as organizers confront renewed enforcement and historic trauma tied to the site.

How Bishop Whipple’s Complex Legacy Is Shaping Protests At The Minneapolis ICE Hub

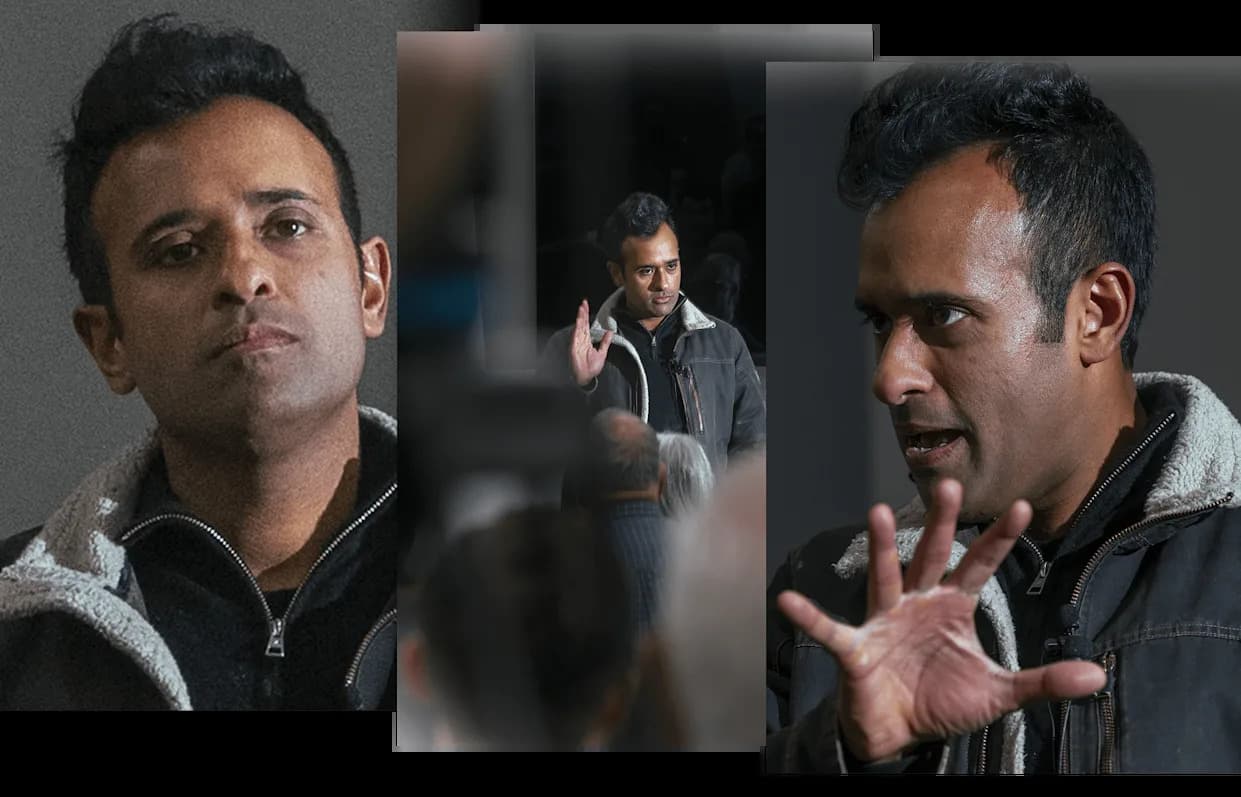

Federal officers in tactical gear have become a common sight along the driveway of the Bishop Henry Whipple Federal Building, a brick complex that sits near the border of Minneapolis and St. Paul. Across from them, protesters shout, organize vigils and sometimes attempt to block vehicles entering and leaving the site.

Why the Building Matters

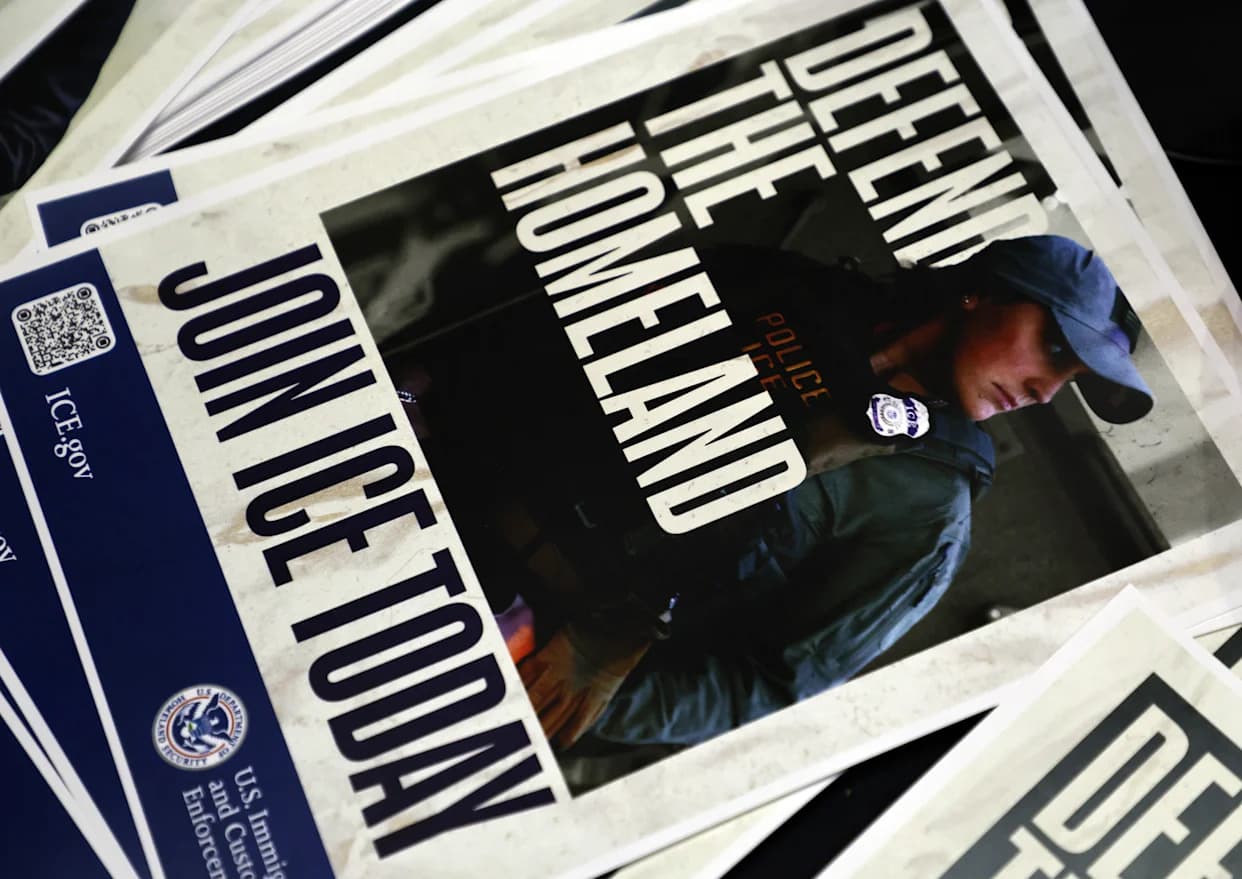

The Whipple Federal Building has emerged as a focal point for tensions since federal agents intensified immigration enforcement in the area and an ICE officer shot and killed Minneapolis resident Renee Good on January 7. The facility houses immigration processing, hearings and temporary detention — operations that have heightened fear, anger and community response.

Whipple’s Legacy: Advocacy and Contradiction

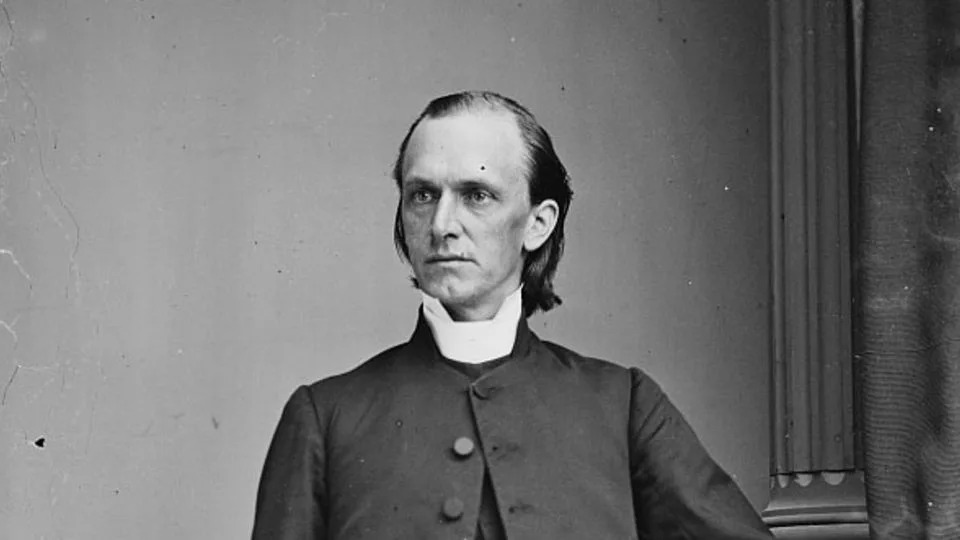

Bishop Henry Benjamin Whipple, Minnesota’s first Episcopal bishop in the mid- to late 1800s, is remembered for advocating on behalf of Dakota and Ojibwe communities and for confronting government officials on matters affecting Indigenous people. Yet historians emphasize his legacy is mixed: while he defended Native Americans against some abuses, his approach was paternalistic and helped promote assimilationist policies, including support for Indian boarding schools that removed children from their families and sought to erase Indigenous languages and cultures.

“He spent his whole ministry… standing with Jesus on the side of those who were marginalized and excluded,” said Craig Loya, current bishop of the Episcopal Church in Minnesota, while also acknowledging Whipple’s complicated record.

From 2019 Campaigns To Present-Day Action

In 2019, faith and community leaders launched the "What Would Whipple Do?" campaign, arguing that Whipple would not have wanted his name on a building that houses immigration enforcement and deportation operations. The movement — led by the Episcopal Church in Minnesota, the Minnesota Council of Churches and the Interfaith Coalition on Immigration — sought to remove the bishop’s name and to mobilize support for detained migrants. The building was named for Whipple when it opened in 1969 at the initiative of then-Sen. Walter Mondale; officials note renaming would likely require Congressional action.

Although the public campaign subsided, organizers say the effort evolved into direct services, legal support and regular vigils. Leaders report that enforcement has intensified since 2019, prompting greater urgency and expanded aid networks.

Indigenous Perspectives And Historic Trauma

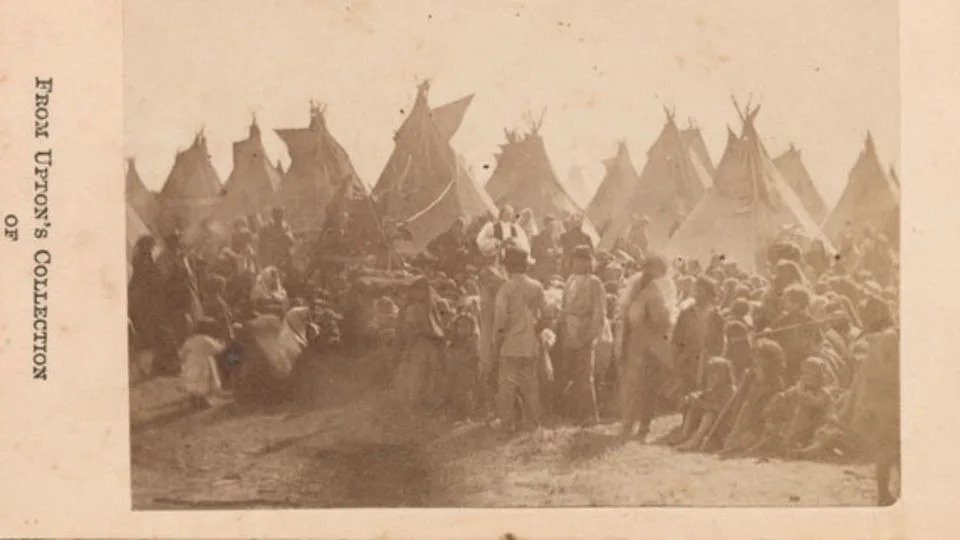

The Whipple building sits on land that is part of Fort Snelling and the Bdote — the Dakota place of creation where the Minnesota and Mississippi rivers meet and a site sacred to the Dakota people for more than a millennium. Ramona Kitto Stately, of the Santee Dakota Nation, and other Indigenous leaders say recent ICE actions near the site revive historical trauma linked to forced marches, detention and family separations following the 1862 US-Dakota War.

Kitto Stately described a Dakota term, "wicayuze" — translated as "men snatchers" — used historically for people who seized community members. For many Indigenous residents, being stopped, questioned or taken to the Whipple building echoes those prior injustices.

Continuing Resistance

Protests and monitoring efforts increased after the January 7 shooting. Demonstrators, interfaith coalitions and Native organizations have held monthly vigils, accompanied detained people to hearings, provided legal aid and documented enforcement activity. Groups like the Native American Rights Fund have publicly called for an end to aggressive ICE operations, while local faith leaders continue to press for humane treatment and systemic change.

What organizers stress: removing Whipple’s name would not resolve the underlying policies and practices that activists and community leaders say must change. Many see the bishop’s imperfect legacy as both a moral spur and a reminder of how advocacy can fall short.

For now, the Whipple Federal Building remains a contested space: physically important to federal immigration work, symbolically charged for Indigenous communities and central to an ongoing local effort to protect and support people affected by enforcement actions.

Help us improve.