Generations of a newly described burrowing bee, Osnidum almontei, nested inside the empty tooth sockets of a fossil jawbone recovered from a Hispaniola cave. Micro-CT scans reveal repeated use of the same cavities, indicating nest fidelity and multi-generational occupation. Researchers found similar nesting cells throughout the deposit, including in a sloth jawbone, suggesting the cave served as a long-term nesting aggregation site. The findings are detailed in a paper published in Royal Society Open Science.

Bees in the Bones: Ancient Solitary Bees Nested Inside a Fossil Jawbone in a Hispaniola Cave

Generations of ancient solitary bees established nests inside the empty tooth sockets of a fossilized jawbone recently excavated from a cave on the Caribbean island of Hispaniola. This surprising discovery — the first documented case of fossil cavities being reused by bees — offers a rare behavioral snapshot of extinct bees making homes out of existing structures.

What Was Found

Paleontologists identified the jawbone as likely belonging to a capybara-like rodent, Plagiodontia araeum, which was probably carried into the cave by an owl that preyied on the now-extinct mammal and discarded the remains. Over time, the jaw’s teeth loosened and scattered while the bone was buried in fine clay silt. Into the resulting dental alveoli — the empty tooth sockets — a newly described burrowing bee species, Osnidum almontei, established multi-generational nesting cells.

How the Evidence Was Recognized

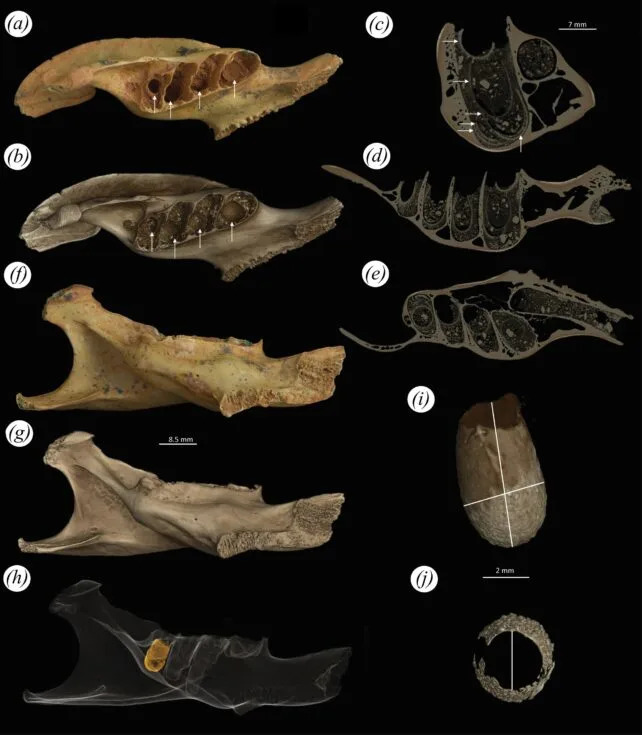

Paleontologist Lázaro Viñola López, while excavating bones for the Florida Museum of Natural History, noticed an unusually smooth inner surface in one alveolus. Micro-computed tomography (micro-CT) scans of the host bones documented repeated use of the same cavities, consistent with nest fidelity — the tendency of individual bees or a species to reuse particular nesting sites.

"Micro-computed tomography scans of the host bones show multi-generational use of the same cavity, suggesting repeated use and some degree of nest fidelity," Viñola López and colleagues write in their paper.

Broader Context and Significance

Once the researchers knew what to look for, they found many additional examples of bee cells preserved within bones across the sediment deposit, including one set inside a sloth jawbone. Although these structures are technically trace fossils (ichnofossils) rather than preserved bee bodies, they provide valuable behavioral information: the bees were highly opportunistic and used every available bony chamber within the deposit. The abundance of nests suggests the cave functioned as a long-term nesting aggregation site for this solitary bee species.

Why it matters: The discovery expands how scientists interpret fossil deposits by revealing that animals sometimes reused organic remains as nesting sites. It also offers rare direct insight into nesting behavior and site fidelity in ancient solitary bees, information usually impossible to glean from body fossils alone.

The study is published in Royal Society Open Science and was reported by researchers associated with the Florida Museum of Natural History.