Researchers have recovered and sequenced RNA from a permafrost‑preserved woolly mammoth specimen known as Yuka, dating to roughly 39,000–40,000 years ago. The find — which appears to be the oldest RNA ever sequenced — challenges the long‑standing assumption that RNA cannot survive outside modern laboratory conditions for tens of thousands of years.

RNA differs from DNA in many key ways, which is why this discovery was so scientifically valuable.©Natali _ Mis/Shutterstock.com

Why This Matters

RNA Offers a Snapshot of Life: Unlike DNA, which records an organism’s genetic blueprint, RNA indicates which genes were active in a tissue at the time it was preserved. That makes RNA a unique window into physiology — metabolism, muscle activity, stress responses and other cellular processes — rather than just heredity.

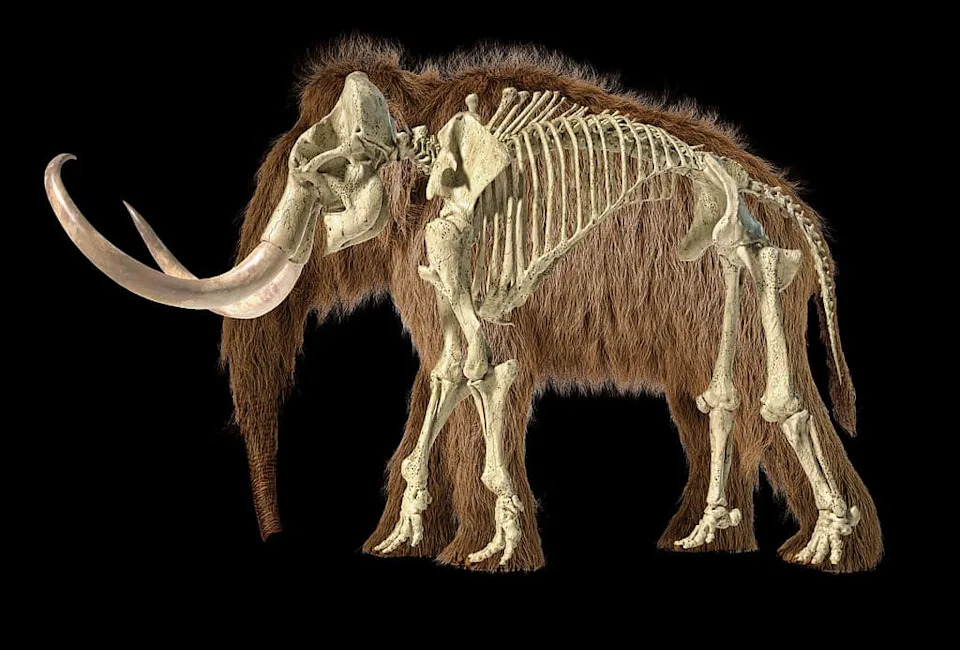

RNA was preserved by the permafrost conditions of this Ice Age-era creature.©leonello/iStock via Getty Images

How the RNA Survived

The research team recovered RNA from muscle tissue preserved in Siberian permafrost, where consistently cold and stable conditions acted like a natural freezer. The scientists tested multiple Ice Age specimens and found that only a subset yielded usable RNA, emphasizing how exceptional the preservation must be for fragile molecules to persist.

Upon researching the uncovered RNA, the mammoth known as Yuka was actually determined to be a male mammoth rather than a female.©Tracy O / CC BY-SA 2.0 –Original/License

Key Findings From Yuka

MicroRNAs Preserved: Among the most notable results were microRNAs — short noncoding RNAs that regulate gene expression. These molecules provide direct clues about how mammoth tissues controlled gene activity and point to physiological states rather than just genetic sequences.

Given this discovery, researchers are eager to explore other Ice Age specimens, as their RNA may also be preserved and full of additional clues about the ecosystem.©Dotted Yeti/Shutterstock.com

Sex Reassessment: Molecular evidence from RNA indicated that Yuka was male, overturning prior sex assignments based on morphology. This example illustrates how molecular data can correct visual or contextual misinterpretations of ancient remains.

Scientists and research companies are attempting to bring back the woolly mammoth, but it’s important to question the effects this might have on our modern ecosystems.©iStock.com/leonello

Implications for Science and De-Extinction

This discovery expands paleogenomics from static DNA sequences to dynamic gene‑expression information and opens possibilities for surveying other permafrost specimens for preserved RNA. Such data could reveal tissue‑level biology, adaptations to cold, and how extinct megafauna shaped their ecosystems.

This discovery is just the first step in many more scientific breakthroughs to come using RNA rather than just DNA.©Billion Photos/Shutterstock.com

That said, recovering ancient RNA is not a shortcut to de‑extinction. While gene‑regulation data could help refine trait models, it does not solve the profound biological and ethical challenges of resurrection — including gestation, development, animal welfare, and whether a resurrected organism would fit modern ecosystems. The IUCN Species Survival Commission cautions that de‑extinction projects may create ecological proxies that require careful, conservation‑focused evaluation.

Looking Ahead

Yuka’s RNA demonstrates that, under exceptional preservation conditions, biological information about gene regulation can survive for tens of thousands of years. Researchers are now eager to survey additional Ice Age remains for preserved RNA, which could yield deeper insights into the physiology, behavior, and ecological roles of extinct animals.

Bottom Line: The Yuka RNA find is a rare—and scientifically rich—glimpse of ancient life at the molecular level. It broadens what scientists can learn about extinct species while highlighting how rare and fragile these data are.