A PNAS study analyzing MRI scans from 26 astronauts and 24 controls reports that the brain can shift position inside the skull during prolonged microgravity, moving backward, upward, and rotating slightly in pitch. The largest observed displacement was about 2.5 mm, and anatomical changes often took six months or more to recede, with some persisting beyond follow-up. Larger shifts in sensory regions correlated with poorer balance recovery, raising concerns for long missions and for possible developmental effects if humans are born and raised in low gravity.

Study: Human Brains Re‑Seat Inside the Skull During Long Spaceflights — Potential Implications for Long Missions

New research in PNAS finds predictable shifts in brain position after prolonged exposure to microgravity. The study compared MRI scans from 26 astronauts and 24 control volunteers and reports that the brain can move slightly within the skull during extended weightlessness.

The investigators found a consistent net displacement: the brain tended to move backward and upward and to rotate slightly in the pitch axis compared with its preflight orientation. The largest measured shift was about 2.5 mm. Though small in absolute terms, even millimetre-scale displacements near posterior structures can have meaningful effects on consciousness and sensorimotor function.

Methods and Key Findings

The team combined MRI data from astronauts who had completed long-duration missions with scans from control volunteers who underwent a head-down-tilt protocol designed to simulate some effects of microgravity. Both groups showed brain repositioning, but the effect was stronger and more consistent in the astronaut cohort.

Functional correlations were noted: subjects with larger displacements in sensory-processing regions tended to have more difficulty re-establishing balance after return to Earth. Anatomical changes were slow to resolve—many subjects required roughly six months or longer for shifts to recede, and some changes persisted beyond the study follow-up.

What This Means

These results do not imply that spaceflight is acutely lethal to the brain, but they do show that microgravity can produce measurable anatomical changes with functional consequences. For long-duration missions (and hypothetical multi-year stays), the possibility of cumulative or persistent effects warrants additional study.

One provocative question raised by the findings concerns development in low gravity: could a brain that forms from conception in microgravity develop normally for life on a planet? While colonization of the Moon or Mars is not yet at that stage, mission planners may eventually need to consider whether expectant parents should return to planetary gravity for childbirth and early child-rearing.

Next Steps

The authors call for larger longitudinal studies, more detailed functional testing, and exploration of countermeasures (e.g., artificial gravity, targeted rehabilitation) to protect neural structure and sensorimotor performance during and after long missions.

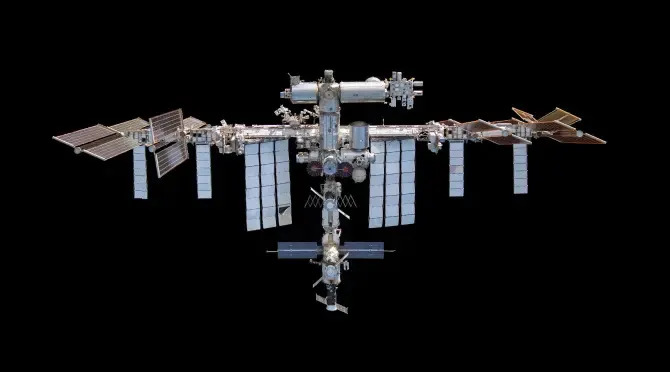

Context note: Long-duration precedent includes Russian cosmonaut Valeri Polyakov’s 437-day Mir mission in the mid-1990s. Image credit: NASA.

Help us improve.