The study tracked microbial recolonization of lava flows from Iceland’s Fagradalsfjall eruptions (2021–2023) by sampling DNA from fresh lava, rainwater, and aerosols. Early colonists arrived mainly via airborne soils and aerosols—species like Sphingomonas echinoides and transient Udaeobacter sp.—but biomass remained extremely low for the first ~100 days. After winter, rainborne microbes reshaped communities, and by year three assemblages stabilized, suggesting a predictable succession that could inform how life might take hold on volcanic worlds such as Mars.

How Life Takes Hold on Barren Lava: Iceland Volcano Study Offers Clues About Life on Mars

As the search for life beyond Earth continues, researchers are asking how communities of organisms first establish themselves on lifeless ground. Mars, for example, features wide stretches of bare basalt left by past volcanic activity, raising the question of whether ancient eruptions could have briefly created more hospitable conditions by warming surfaces, melting ice, and releasing gases.

A new study published in Nature Communications Biology by ecologists and planetary scientists from the University of Arizona and the University of Iceland examines microbial recolonization after three eruptions of Iceland’s Fagradalsfjall volcano between 2021 and 2023. Each eruption repeatedly covered the surrounding tundra with fresh lava, creating a rare opportunity to observe multiple, independent successions on newly formed rock.

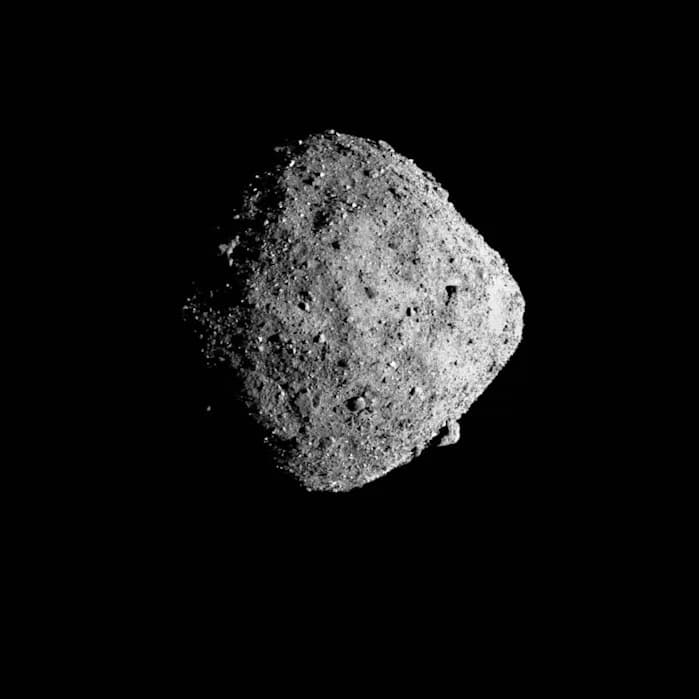

Natural Laboratory: Fresh Lava as a Clean Slate

"The lava coming out of the ground is over 2,000 degrees Fahrenheit, so obviously it is completely sterile," said Nathan Hadland, the study’s first author and a doctoral student at the University of Arizona Lunar and Planetary Laboratory. Each new flow acts as a clean slate, offering a natural experiment to track how microbes arrive and establish themselves on inert rock.

How Microbes Arrive

Over three years the team extracted DNA from recently solidified lava, rainwater, and airborne aerosols to track which microbes arrived, when, and how long they persisted. The earliest arrivals were mostly transported on wind-blown soils and aerosols—species such as Sphingomonas echinoides, a widespread soil bacterium, appeared quickly on fresh flows.

These pioneer species must tolerate extreme conditions: newly cooled lava is hot, extremely dry, and deficient in available nutrients. The researchers detected Udaeobacter sp., a bacterium known for surviving on minimal resources, on just-cooled lava. However, many of these initial colonists declined during the first winter; Udaeobacter dropped off during winter and was gone by roughly one year after emplacement.

Seasonal Shift and Rain-Driven Colonization

Within the first 100 days after emplacement, microbial biomass on the lava remained exceptionally low—comparable to some of the driest, lowest-biomass environments on Earth, such as parts of the Atacama Desert. After winter, the community composition changed markedly: rainwater delivered a suite of new microbes that established more successfully than the earliest wind-borne colonists.

"Seeing this huge shift after the winter was pretty amazing,"

co-author Solange Duhamel said, noting that the seasonal change was strikingly consistent across all three separate eruptions.

Convergence and Stability by Year Three

By the third year after emplacement, microbial assemblages had become more stable, with less turnover between successive communities. Many of the species that persisted were already known from other volcanic terrains in Iceland and Hawaii. Based on their observations and models, the authors propose that colonization of new lava follows a predictable trajectory: sparse initial colonization by hardy, wind- or aerosol-borne microbes, a major shift after seasonal precipitation, and gradual stabilization into a more persistent community.

These findings shed light on how life can establish on bare volcanic surfaces on Earth and offer a framework for thinking about how similar processes might operate on other volcanic worlds, including Mars.

Lead image: Ahsanjayacorp / Shutterstock

This story was originally featured on Nautilus.

Help us improve.