A new study finds the solar wind has carried particles from Earth’s atmosphere to the Moon for billions of years, embedding volatiles in lunar soil. Computer simulations show a magnetized, modern Earth can transfer more atmospheric material to the Moon—especially when the Moon passes through Earth’s magnetotail. The results were validated using Apollo 14 and 17 samples and suggest the lunar regolith may preserve a chemical record of Earth’s ancient atmosphere while offering potential resources for future exploration.

Moon’s Soil Holds Traces of Earth: Study Finds Magnetosphere Channels Atmospheric Gases to the Lunar Surface

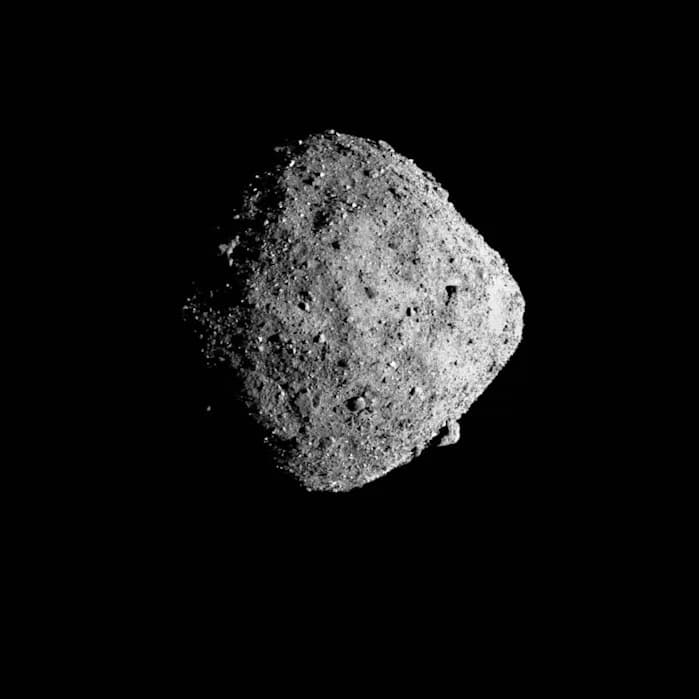

Particles from Earth's atmosphere—swept outward by the solar wind—have been landing on the Moon and mixing into its regolith for billions of years, a new study reports. The research overturns the longstanding idea that Earth's magnetic field simply protected the atmosphere; instead, simulations show the magnetosphere can help channel atmospheric volatiles toward the Moon, a process that continues today.

The team published their results in Nature Communications Earth & Environment, comparing two modeled scenarios: an ancient Earth with a strong solar wind and no magnetic field, and a modern Earth with a weaker solar wind but a strong magnetosphere. The simulations indicate the modern, magnetized Earth is more effective at transferring fragments of Earth’s atmosphere to the Moon—especially during times when the Moon passes through Earth's magnetotail.

How the Transfer Works

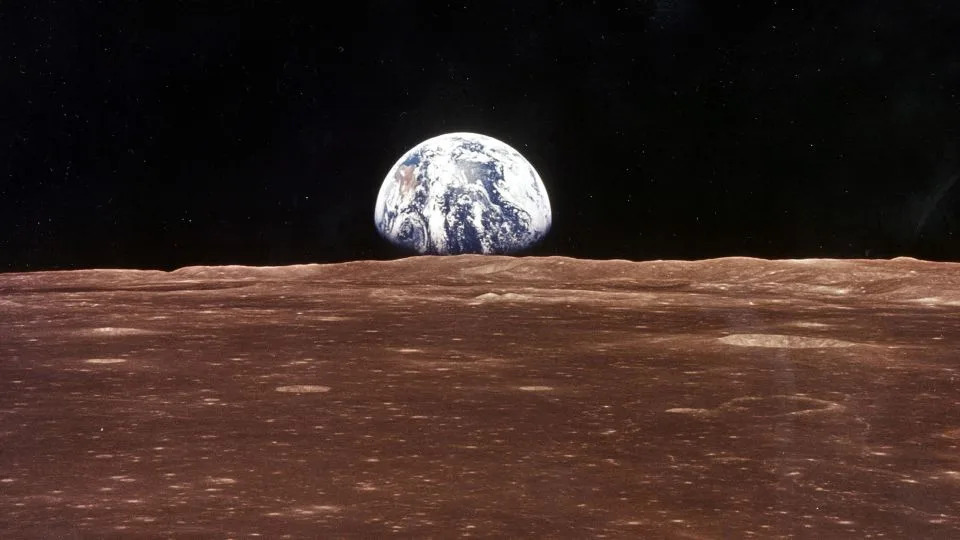

Earth's magnetic field—generated by currents in the molten iron–nickel outer core—forms a magnetosphere that deflects the solar wind. But the magnetosphere also reshapes the atmosphere and opens pathways. According to coauthor Eric Blackman of the University of Rochester, magnetic pressure inflates the upper atmosphere, giving the solar wind greater access to atmospheric particles. When the Moon moves through the magnetotail for several days each month (often near full moon), the field lines create a channel that allows blown atmosphere material to travel more directly to the lunar surface.

Evidence and Validation

The researchers validated their simulations against direct laboratory analyses of Apollo-era lunar samples. Shubhonkar Paramanick, lead author and graduate student at the University of Rochester, noted that the team compared modeled mixing ratios to chemical signatures found in soil returned by the Apollo 14 and 17 missions. The match supports the idea that some oxygen, nitrogen, hydrogen, helium and carbon-bearing molecules in lunar soil originated from Earth as well as from the Sun.

“This means that the Earth has been supplying volatile gases like oxygen and nitrogen to the lunar soil over all this time,” said Blackman.

Why This Matters

Volatile elements implanted in lunar regolith are scientifically valuable and practically important. They could preserve a chemical record of Earth's ancient atmosphere—information tied to planetary evolution and the history of life. Practically, oxygen, hydrogen and nitrogen in lunar soil may be processed to support future exploration: extracting water and fuel components or using ammonia-based fuels that leverage nitrogen deposited by the solar wind.

Independent researchers welcomed the findings. Kentaro Terada (Osaka University), whose 2017 work showed oxygen transported to the Moon, said the new paper provides helpful theoretical corroboration. Simeon Barber (Open University) highlighted that recent sample returns—China’s Chang’e-5 (2020) and Chang’e-6 (2024)—offer fresh opportunities to test these predictions and refine our understanding of Earth–Moon chemical exchange.

Overall, the study reframes the magnetosphere: not only a shield, but also a conduit for subtle, long-term material exchange between Earth and its nearest neighbor. That exchange may leave clues to Earth’s atmospheric past while also contributing to resources future lunar missions could exploit.

Help us improve.