The Moon’s near side has a thinner crust (~25 miles) and widespread basalt plains, while the far side has a thicker crust (~40 miles) and many craters. Chang’e‑6 returned the first samples from the far side’s South Pole‑Aitken basin, and isotope analysis shows heavier potassium in far‑side rocks. Researchers say a massive impact likely vaporized lighter potassium isotopes, redistributing elements to the near side and triggering volcanism. More samples are needed to confirm this impact-driven scenario.

Chang’e‑6 Rocks Suggest Giant Asteroid 'Boiled' the Moon — Explaining Its Lopsided Face

Earth’s Moon is strikingly asymmetric: the hemisphere we see from Earth has a thinner crust and vast dark plains of ancient lava, while the far side is thicker, brighter, and heavily cratered. New analyses of the first samples returned from the lunar far side point to a dramatic explanation — a colossal impact that may have literally boiled parts of the Moon’s interior and reshaped its surface chemistry.

The Moon’s Two Faces

The near side’s crust averages about 25 miles thick, compared with roughly 40 miles for the far side. The near side is dominated by dark basaltic maria — broad plains formed by ancient volcanic lava flows — whereas the far side is brighter and densely pocked with impact craters, a contrast first revealed by the Soviet Luna 3 probe in 1959.

New Samples From the Far Side

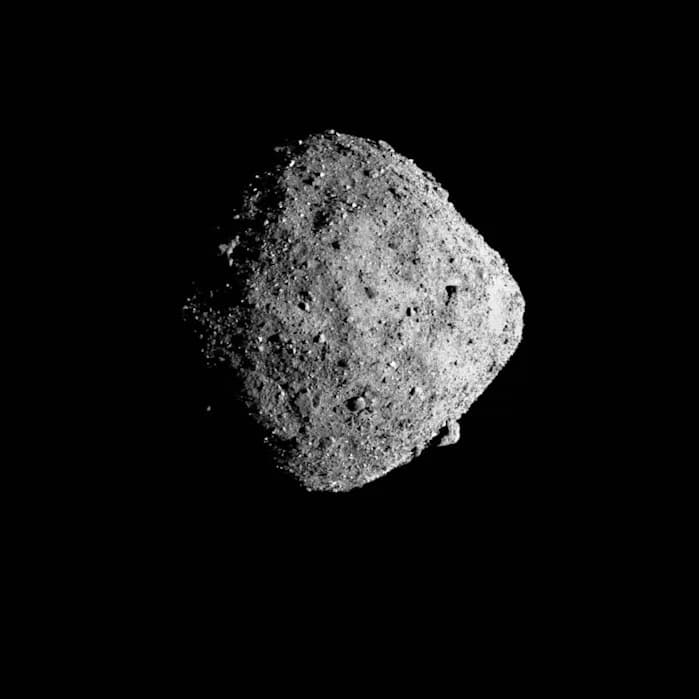

China’s Chang’e‑6 mission returned the first-ever rock and soil samples from the lunar far hemisphere, collected in the South Pole‑Aitken basin. That basin covers nearly a quarter of the Moon’s surface, with a diameter exceeding 1,550 miles and an average depth of about 6 miles — making it one of the largest and deepest impact basins in the solar system.

Isotope Clues Point to a Violent Past

A research team at the Chinese Academy of Sciences analyzed four small fragments of far‑side basalt that contain material derived from the lunar mantle, comparing them with near‑side samples returned by Apollo and Chang’e‑5. They measured potassium and iron isotopes — atoms of the same element that differ by neutron count and mass — and reported their results in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The far‑side samples show significantly heavier potassium isotopic ratios than near‑side rocks; iron isotopes show only a modest enrichment. While volcanic processes can explain the iron differences, the potassium signature is best explained by high‑temperature evaporation: when potassium vaporizes, lighter isotopes preferentially escape, leaving a heavier isotopic residue.

Impact 'Boiling' and Element Redistribution

The authors propose that the impact that created the South Pole‑Aitken basin may have 'boiled' parts of the Moon’s interior, driving volatile and more mobile elements toward the near side and fueling the volcanic activity that produced the near‑side maria. If so, this would show that large impacts can not only excavate basins but also fundamentally alter mantle and crust chemistry.

Implication: Large‑scale collisions can reshape a planetary body's internal composition long after initial formation.

The team cautions that the result is preliminary: more samples from diverse far‑side locations are needed to robustly test the hypothesis. Still, these findings highlight how catastrophic events can have lasting, global effects on planetary structure and evolution.

Help us improve.