Researchers combined Apollo regolith chemistry with magnetospheric simulations and found that Earth's magnetotail channels charged atmospheric ions toward the Moon, especially near full moon. Published Dec. 11 in Communications Earth & Environment, the study overturns a prior idea that Earth's magnetic field blocked such transfers and suggests the exchange began around 3.7 billion years ago and still happens intermittently. Lunar soil could thus preserve a layered record of Earth's atmospheric and magnetic history, valuable for upcoming sample-return missions.

The Moon Has Been Collecting Earth's Air for Billions of Years — New Study Shows Magnetotail Channels Ions to the Lunar Surface

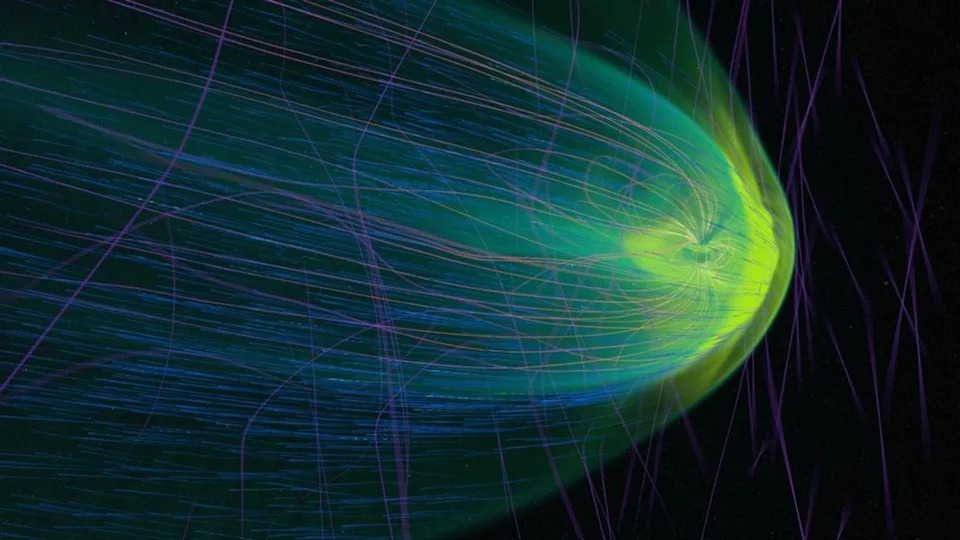

New research indicates the Moon has quietly accumulated tiny fragments of Earth's atmosphere for billions of years. Combining chemical analyses of Apollo-era lunar soil with computer simulations of Earth's magnetosphere, scientists conclude that charged atmospheric particles, or ions, are funneled toward the Moon along magnetic field lines in Earth’s magnetotail.

This finding, published Dec. 11 in Communications Earth & Environment, overturns a two-decade-old assumption that Earth’s magnetosphere would have simply trapped ions escaping from our atmosphere. Instead, the study shows the magnetotail can act like an invisible highway, guiding ions away from Earth and toward the lunar surface. The greatest transfer occurs when the Moon passes through Earth’s magnetotail, a configuration that commonly happens near the full moon.

Why This Matters

When Apollo missions returned lunar regolith in the early 1970s, scientists found traces of volatile substances—materials that vaporize at relatively low temperatures, including water, carbon dioxide, helium, argon, and nitrogen. Later work suggested some of those nitrogen ions originated in Earth’s upper atmosphere and were driven outward by solar wind. The new study integrates those chemical fingerprints with magnetospheric models and suggests the transfer has been active since Earth’s magnetic field stabilized roughly 3.7 billion years ago.

Rather than containing only remnants of Earth’s earliest atmosphere, lunar soil may preserve a layered record of atmospheric and magnetic history. That record could help scientists reconstruct changes in Earth’s atmosphere and magnetosphere through deep time.

"By combining data from particles preserved in lunar soil with computational modeling of how solar wind interacts with Earth’s atmosphere, we can trace the history of Earth's atmosphere and its magnetic field," said Eric Blackman, theoretical astrophysicist and plasma physicist at the University of Rochester.

Implications for Future Missions and Planetary Science

Upcoming and recent sample-return missions could exploit this natural archive. Regolith returned by NASA's Artemis program and by Chinese lunar missions may contain records of atmospheric composition and magnetospheric behavior across billions of years. That information could fill gaps in Earth's geological and atmospheric history and inform models of atmospheric loss and retention on other planets.

The results also have broader implications beyond Earth. Study lead author Shubhonkar Paramanick notes that understanding how magnetic fields and solar wind interact to move atmospheric particles could shed light on early atmospheric escape on planets such as Mars, which today lacks a global magnetic field but likely had one in the past. Such processes are central to assessing long-term planetary habitability.

Planetary bodies across the solar system lose material to the solar wind: Mercury frequently shows a comet-like tail of eroded surface material, and the Moon itself produces a tail of sodium ions that Earth periodically passes through. This new work places Earth-to-Moon transfer of atmospheric ions in that broader context, showing that our planet is not immune to interplanetary exchange.

"Our study may also have broader implications for understanding early atmospheric escape on planets like Mars," said Shubhonkar Paramanick, planetary scientist at the University of Rochester. "Future research could help scientists gain insight into how these processes shape planetary habitability."

What remains to be done: More targeted lunar sampling at known stratigraphic depths, improved models of long-term magnetospheric evolution, and coordinated observations of ion flows during Moon-magnetotail encounters will help confirm the timing, rates, and composition of the transfer.

Help us improve.