The first samples from the Moon's far side, returned by China's Chang'e‑6 mission, show heavier potassium and iron isotopes than near‑side basalts. Researchers conclude that the South Pole–Aitken basin‑forming impact likely vaporized lighter isotopes from the mantle, producing the hemispheric chemical asymmetry. Volcanic processes cannot account for the potassium isotope shift, and the finding implies large impacts can permanently alter a world's interior. Results appear in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Chang'e‑6 Samples Suggest Giant Impact Altered Moon's Interior—and Left It Lopsided

The first material ever returned from the Moon's far side is pointing to a dramatic cause for the satellite's long-noted hemispheric differences: a colossal ancient impact that changed the Moon's chemistry from the inside out.

New Isotope Evidence From the Far Side

Scientists from the Chinese Academy of Sciences analyzed dust returned to Earth by China's Chang'e‑6 mission in 2024. The sample, collected from the South Pole–Aitken Basin—the largest known impact feature on the Moon—shows distinct isotopic signatures for potassium and iron compared with basalts returned from the near side by the Apollo missions and China's Chang'e‑5 mission.

Isotopes are variants of an element with different numbers of neutrons; they behave chemically the same but have different masses. The Chang'e‑6 basalt contains relatively heavier potassium and iron isotopes, while Apollo and Chang'e‑5 basalts are enriched in the lighter isotopes of those elements.

Impact, Not Volcanism, Explains the Signature

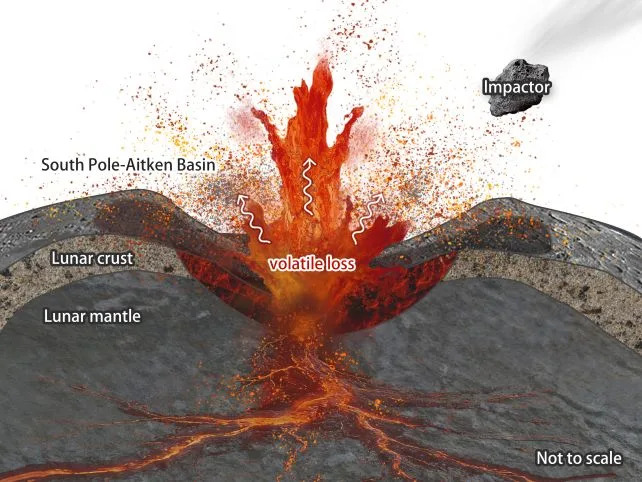

According to the team led by planetary scientist Heng‑Ci Tian, magmatic processes can account for some iron isotope variations, but they cannot explain the potassium isotopic shift observed in the far‑side sample. The researchers argue that the most plausible explanation is intense heating and partial vaporization of mantle material during the South Pole–Aitken basin‑forming impact. Lighter isotopes preferentially evaporate at high temperatures, leaving behind a mantle reservoir enriched in heavier isotopes.

"Although magmatic processes can explain the iron isotopic data, the potassium isotopes necessitate a mantle source with a heavier potassium isotopic composition on the farside than on the nearside," the authors write, adding that the pattern likely resulted from potassium evaporation caused by the South Pole–Aitken impact.

Because that impact excavated deeply into the Moon's mantle, its effects could extend to substantial depths—offering a coherent explanation for the hemispheric isotopic differences. The study suggests that very large impacts do more than scar a surface: they can permanently reshape a body's interior composition and dynamics.

Implications and Next Steps

This result links several previously puzzling observations about the Moon's far side and provides a new tool for interpreting lunar geochemistry. The impact may even have driven hemisphere‑scale mantle convection, but confirming that idea will require more samples from other far‑side regions and further modeling.

The research has been published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Help us improve.