TOI-561 b is an ultra-short-period super‑Earth that may host a global magma ocean beneath a dense atmosphere of vaporized rock, according to Carnegie Science researchers. JWST’s NIRSpec observed the planet for 37 hours and found its dayside brightness temperature (~1,800°C) is much cooler than the ~2,700°C expected for an airless world, implying an atmosphere. The planet orbits an ancient, iron-poor star in the Milky Way’s thick disk and has a low bulk density, which could reflect a small iron core or an extended atmosphere. Researchers suggest a magma‑ocean–atmosphere equilibrium could replenish and store volatiles, but follow‑up work is needed to confirm composition and mechanisms.

Ancient 'Wet Lava Ball' TOI-561 b: JWST Finds Evidence of a Long-Lived Atmosphere on a Molten Super‑Earth

A scorching world of molten rock shrouded by a dense veil of vaporized minerals may be the strongest evidence yet that a rocky exoplanet outside our Solar System can retain an atmosphere. New observations of TOI-561 b, led by Carnegie Science researchers, reveal a surprising and durable climate on this ultra-hot super‑Earth.

TOI-561 b at a glance

TOI-561 b is an ultra-short-period (USP) super‑Earth that completes an orbit in under 11 hours. It lies less than 1.6 million kilometers (0.99 million miles) from its host star—about one‑fortieth the Sun–Mercury distance—so the planet is tidally locked, with a permanently sunlit dayside and a permanently dark nightside. The planet has roughly twice Earth’s mass and a radius about 1.4 times that of Earth.

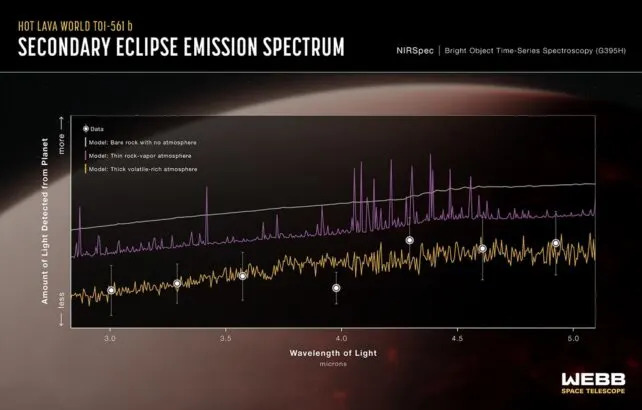

Key observations from JWST

The James Webb Space Telescope’s NIRSpec instrument observed TOI-561 b for 37 hours (nearly four full orbits) and measured the planet’s dayside near‑infrared brightness. An airless dayside should glow at roughly 2,700°C (4,900°F), but the measured emission corresponds to a cooler brightness temperature near 1,800°C. That discrepancy strongly suggests the presence of a substantial atmosphere altering the thermal emission.

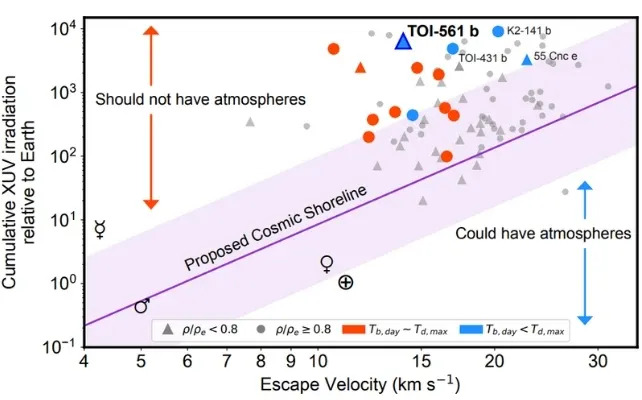

“Based on what we know about other systems, astronomers would have predicted that a planet like this is too small and hot to retain its own atmosphere for long after formation,” said Carnegie Science astronomer Nicole Wallack.

Why the planet’s density and host star matter

TOI-561 b has an unusually low bulk density—about four times the density of water. This low density could indicate a relatively small iron core and lighter rocky composition, consistent with formation around an iron-poor star. The host star itself is ancient (≈10 billion years), slightly less massive and cooler than the Sun, depleted in iron but enriched in alpha elements such as oxygen, magnesium and silicon, and belongs to the Milky Way’s thick disk.

How an atmosphere might persist for billions of years

The research team proposes that TOI-561 b maintains a dynamic equilibrium between a global magma ocean and an overlying atmosphere of vaporized rock and volatile species. In this picture, gases continuously outgas from the hot crust and magma to replenish the atmosphere while some volatiles escape to space. Simultaneously, the molten surface can act as a reservoir that reabsorbs gases, slowing net atmospheric loss. Chemical interactions with iron in the magma or core may also help sequester and recycle volatiles, aiding long‑term retention.

Atmospheric circulation could further moderate the dayside temperature by transporting heat to the nightside, while vapors (for example, silicate species or other high‑temperature volatiles) can absorb and reemit near‑infrared radiation, reducing the observed dayside brightness.

Open questions and next steps

Although the JWST measurements strongly suggest an atmosphere, pinpointing its composition, thickness and the detailed mechanisms that allow it to survive requires further theoretical work and follow‑up observations. The study appears in The Astrophysical Journal Letters and highlights how JWST is reshaping our view of the most extreme rocky worlds.

Why this matters

TOI-561 b challenges conventional expectations about atmospheric loss on close‑in rocky planets and offers a natural laboratory to study magma–atmosphere interactions, volatile cycling, and the chemistry of ultra‑hot surfaces. Understanding such planets helps refine models of planetary formation, evolution and habitability across the Galaxy.