Ancient Mars was warmer and volcanically active, and silica deposits discovered by the Spirit rover at Home Plate in Gusev crater resemble opaline sinter formed by terrestrial hot springs. The deposits include fingerlike textures similar to sinter‑related stromatolites, but no organic material has been confirmed. If verified as hot‑spring sinter, these deposits would be prime astrobiology targets; Yellowstone remains a valuable analogue for interpreting such evidence.

Could Mars Have Hosted Yellowstone‑Style Hot Springs?

Billions of years ago Mars was warmer, wetter and geologically active. Combined with abundant volcanism, those conditions raise a compelling question: did Mars ever host hot springs or geysers similar to those at Yellowstone?

What Mars was like in the past

Today Mars is cold and dry, with most water locked in polar caps and subsurface ice. But ancient Mars had a thicker atmosphere and a climate capable of supporting liquid water at the surface for extended periods. Modern exploration—by orbiters, landers and rovers—has revealed clear signs of past surface water, extensive volcanism and a rich mineral record.

Silica discoveries at Home Plate

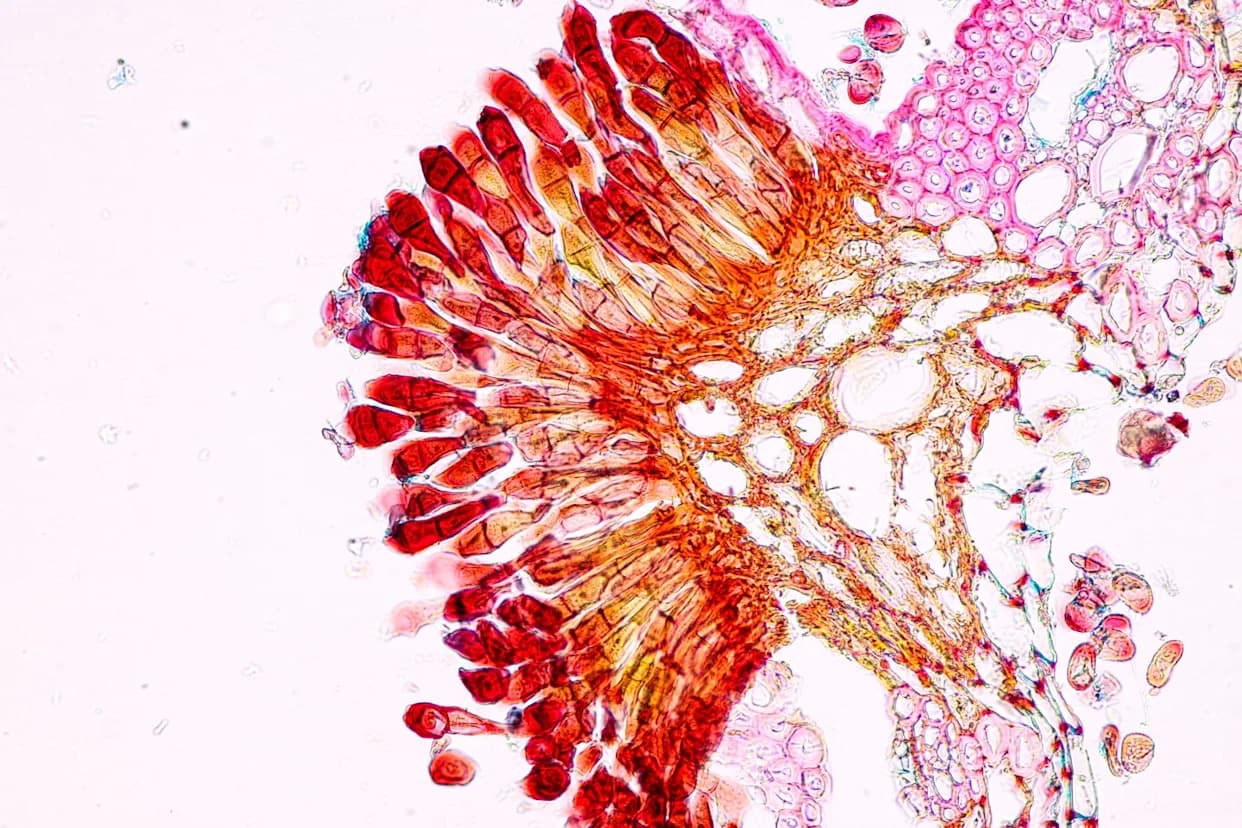

In 2007 the Mars Exploration Rover Spirit discovered unusual silica-rich deposits near a feature nicknamed Home Plate in Gusev crater. These opaline silica occurrences attracted attention because they resemble the porous, white silica (sinter) that forms around hot springs and geysers on Earth, including at Yellowstone.

How silica can form

On Earth there are two principal ways to produce opaline silica deposits in volcanic terrains:

- Hydrothermal precipitation (sinter): Hot, silica-rich waters circulating through volcanic (often rhyolitic) rocks carry dissolved silica to the surface. As those fluids cool at springs and geysers, silica precipitates in layered deposits and mounds called sinter.

- Acid‑sulfate leaching: Volcanic gases produce sulfuric acid that reacts with near-surface silicate rocks, leaching iron and magnesium and leaving a residual opaline silica cap.

The spatial association of the Home Plate silica with volcanic ash and basaltic rocks supports a hydrothermal interpretation, although acid‑sulfate processes could also play a role in some settings.

Fingerlike structures and the search for life

Some of the silica bodies photographed by Spirit show tiny fingerlike textures that resemble stromatolite-like forms found in terrestrial sinter deposits. On Earth, those structures often grow where microbial mats interact with precipitating silica. However, the Martian examples are mineralogical in nature: no organic material has yet been confirmed within them, and abiotic processes can produce similar morphologies.

Even without confirmed organics, silica sinter is an excellent target for astrobiology because it preserves fine-scale textures and can entomb biomarkers. Thus, ancient hot-spring deposits on Mars—if correctly identified—would be high-priority locations in the search for ancient microbial life.

Broader context: geysers and icy moons

Hydrothermal and geyser-like activity is not unique to Mars. Plume activity has been observed on bodies such as Saturn’s moon Enceladus and Neptune’s Triton, and Jupiter’s moon Europa likely harbors a subsurface ocean that may vent material into space. NASA’s Europa Clipper, launched in October 2024 and scheduled to arrive in 2030, will investigate Europa’s habitability.

Why Yellowstone is a useful analogue

Yellowstone provides a living laboratory where volcanic calderas, geysers, hydrothermal minerals and thermophilic microbial communities interact. Studying how sinter forms and preserves biological signatures on Earth helps scientists develop strategies to recognize and interpret potential biosignatures in ancient hydrothermal deposits on Mars.

Further reading: Ruff, S.W., Campbell, K.A., Van Kranendonk, M.J., Rice, M.S. & Farmer, J.D. (2020). "The case for ancient hot springs in Gusev crater, Mars." Astrobiology, 20(4):475–499. https://doi.org/10.1089/ast.2019.2044

Help us improve.