Two worked wooden implements recovered at Greece’s Marathousa 1 site have been dated to about 430,000 years ago, potentially making them the oldest known hand-held wooden tools. Microscopic analysis revealed chopping and carving marks on an alder piece and a tiny willow/poplar fragment, indicating deliberate shaping and use. Associated stone tools and elephant remains place these finds in a lakeshore butchery context during the Middle Pleistocene, expanding evidence for early wood technology.

430,000-Year-Old Wooden Implements From Greece May Be the Oldest Handheld Tools

Researchers report that two worked wooden implements recovered from the Marathousa 1 site in the central Peloponnese of Greece have been dated to about 430,000 years ago. If confirmed as tools, these specimens represent the earliest known hand-held wooden tools and push back the documented use of fashioned wood by roughly 40,000 years.

What Was Found

Archaeologists recovered two worked pieces of wood: a larger implement made of alder and a much smaller fragment of either willow or poplar. Both objects show microscopic chopping and carving marks consistent with deliberate shaping and repeated use. A third fragment examined by the team showed marks made by animal claws rather than human modification.

Where and When

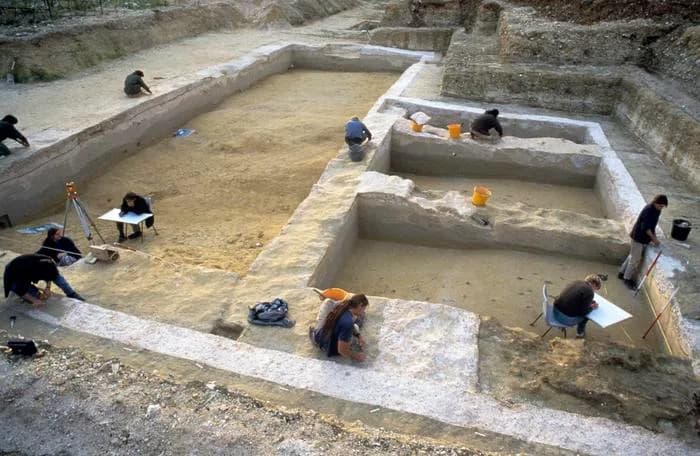

The finds come from Marathousa 1, a wetland/lakeshore locality in central Peloponnese that preserves organic remains unusually well. The site was active during the Middle Pleistocene (roughly 774,000–129,000 years ago) and produced stone tools as well as the remains of an elephant and other animals, suggesting a lakeshore butchery and activity area.

Why It Matters

Wood rarely survives in the archaeological record unless conditions are exceptional. Annemieke Milks, a specialist in early wood technology at the University of Reading, said the team examined surfaces under microscopes and identified machining marks such as chopping and carving. The larger alder object appears to have been shaped and heavily used—possibly as a digging stick or for removing bark—while the very small willow/poplar piece fits a finger-held function and may have assisted in producing or finishing stone tools.

“These finds extend the temporal range of early wooden tools,” the authors write, noting that the assemblage documents both larger expedient handheld tools and a uniquely small, likely finger-held implement.

Context and Comparisons

The study, published in PNAS by researchers from the University of Tübingen and the University of Reading, highlights Marathousa 1's exceptional preservation. The team compares the discovery to other early wooden remains—such as a circa-476,000-year-old wooden structural element from Kalambo Falls, Zambia—but emphasizes that those earlier finds were not clearly tools. Known wooden implements from other sites (United Kingdom, Germany, China, Zambia) are generally younger than the Marathousa pieces.

The presence of stone tools and butchered megafauna at the site, together with carnivore tooth marks near human-modified bones, illustrates a dynamic environment of hominin activity, scavenging, and competition with large predators.

Conclusions

These Marathousa 1 specimens broaden our picture of early hominin technology by adding well-documented examples of wood working and use during the Middle Pleistocene. If accepted by the wider field, they show that early humans not only used stone but also deliberately shaped and used wooden tools considerably earlier than previously confirmed.

Study: Researchers from the University of Tübingen and the University of Reading; published in PNAS. Materials examined using microscopic surface analysis. Site: Marathousa 1, central Peloponnese, Greece.

Help us improve.