The discovery of buphandrine and epibuphanisine—alkaloids from the Boophone disticha (gifbol) bulb—on 60,000-year-old quartz backed microliths from Umhlatuzana Rock Shelter provides the oldest direct evidence of poisoned arrows. The residues on five of ten points, and the same compounds on 250-year-old historical tips, indicate a long regional tradition and chemical stability. Researchers say the find demonstrates sophisticated botanical knowledge, planning, and delayed-cause reasoning among Late Pleistocene hunter-gatherers.

60,000-Year-Old Poisoned Arrows Reveal Sophisticated Stone Age Hunting And Botanical Knowledge

Scientists have identified chemical traces of plant toxins on Stone Age arrow tips from South Africa, providing the earliest direct evidence of poisoned arrows and revealing unexpectedly advanced hunting strategies and botanical knowledge among Late Pleistocene hunter-gatherers.

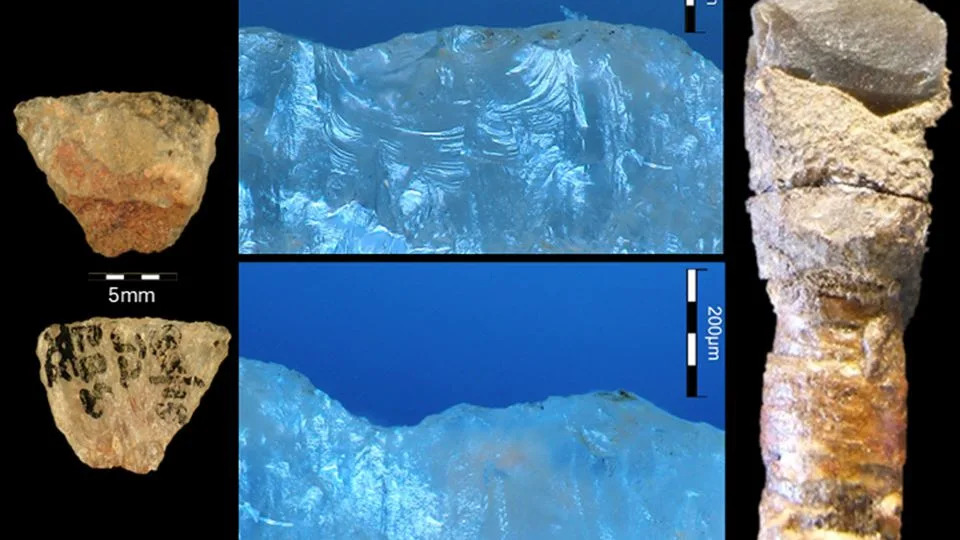

What was found: Chemical analyses of ten small quartz backed microliths recovered from the Umhlatuzana Rock Shelter (KwaZulu-Natal) detected two alkaloids—buphandrine and epibuphanisine—on five of the points. These compounds derive from the bulb of Boophone disticha (locally known as the gifbol or "poison bulb"). The arrow tips were excavated in 1985 and are dated to roughly 60,000 years ago; the work appears in Science Advances.

How the poison was used: The researchers propose that hunter-gatherers harvested toxic sap from the gifbol bulb—by stabbing or cutting it—and then applied the substance to arrow points. They may have concentrated the toxins with heat or sunlight before smearing them on the tips. In persistence hunting, poisoned arrows often did not kill instantly; instead the toxins weakened prey over hours, making it easier to track and capture the animal.

Why the residues survived

Chemical features of the two alkaloids—such as low solubility in water and relative molecular stability—helped them persist on buried stone tools for tens of thousands of years. To reinforce their interpretation, the team analyzed four historical arrow tips (about 250 years old) collected in South Africa and later held in Sweden; those points contained the same alkaloids, indicating a long regional tradition of gifbol use and demonstrating the compounds’ preservational resilience.

Implications for cognition, culture and technology

The find implies that Late Pleistocene hunter-gatherers possessed detailed ecological and botanical knowledge (which plants were toxic and how to extract and possibly concentrate their compounds), as well as advanced planning and an appreciation of delayed cause-and-effect: they anticipated that a poisoned wound would incapacitate prey hours later. The authors argue this behavior reflects complex cultural practices and sophisticated hunting strategies.

“Poisoned arrows did not usually kill prey instantly,” write the authors, noting that toxins shortened the time and energy required to track a wounded animal.

Independent commentators praised the chemical verification of minute residues as a rare and important demonstration of complex behavior in deep prehistory.

Context in the archaeological record

Before this discovery, the earliest direct chemical evidence for poisoned hunting tools came from much younger contexts—bone-tipped arrows in an Egyptian tomb dated to about 4,431–4,000 years Before Present and finds from Kruger Cave in South Africa dated to roughly 6,700 years BP. Other regional evidence suggesting long-term use of poisons includes an applicator from Border Cave dated to ~24,000 years ago and a lump of beeswax (~35,000 years old) that could have been used as adhesive.

Some archaeologists place the origins of bow-and-arrow technology even earlier (perhaps 80,000 years ago in Africa and Asia), and view the new results as reinforcing the idea that complex hunting technology and associated cognitive skills were part of early Homo sapiens lifeways as they spread across the globe.

Health effects and practical notes

Tests on animals and historical reports indicate Boophone disticha toxins can kill small mammals within 20–30 minutes and, in humans, can cause symptoms including nausea, respiratory paralysis, pulmonary edema and a weak pulse. The authors note that some toxins degrade with heat or are only dangerous if entering the bloodstream, which would have influenced how hunters handled and consumed game.

Next steps: The research team plans to analyze more sites in southern Africa to assess how widespread poison-arrow use was during the Late Pleistocene and to further explore the cultural and cognitive capacities of early hunter-gatherer groups.

Source: Study published in Science Advances; lead author Sven Isaksson, Stockholm University.

Help us improve.