Researchers found 35 horned or antlered mammal skulls deliberately placed inside Des-Cubierta cave in central Iberia, alongside more than 1,400 Mousterian stone tools. Detailed spatial analysis separated human activity from later rockfalls and indicates skull placements occurred repeatedly between roughly 135,000 and 43,000 years ago. The pattern suggests a long-lasting cultural practice transmitted across generations, though the skulls' exact purpose remains unknown.

Neanderthals Repeatedly Placed 35 Horned Skulls in a Spanish Cave — Evidence of Long-Lasting Cultural Practice

Archaeologists report that Neanderthals deliberately collected and arranged skulls of horned and antlered mammals inside Des-Cubierta cave in central Iberia, providing strong evidence of complex cultural behaviour that persisted for tens of thousands of years.

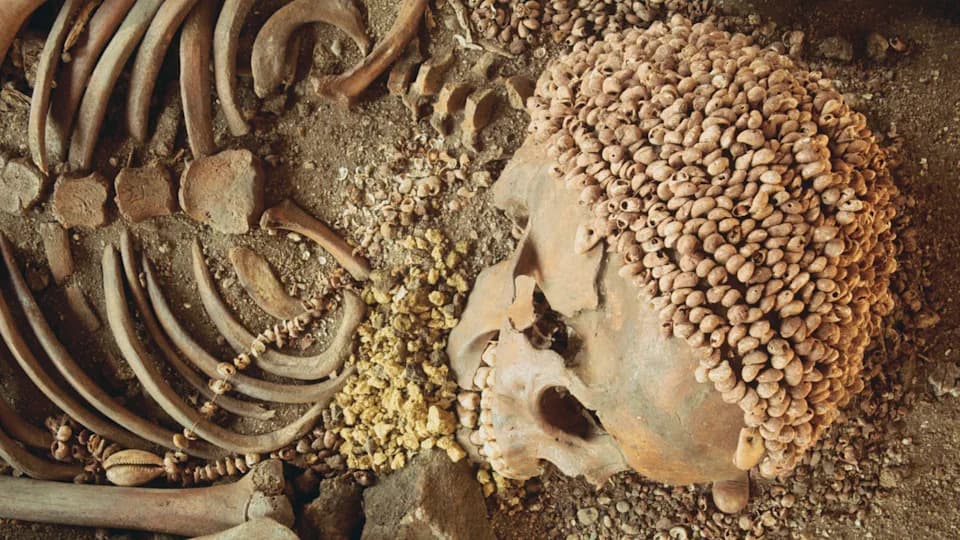

Des-Cubierta cave, first discovered in 2009, yielded an unusual assemblage when researchers announced in 2023 that they had uncovered 35 large mammal skulls in a single stratigraphic layer. Most mandibles were absent, and every skull came from horned or antlered species, including steppe bison and aurochs. The same layer also contained more than 1,400 stone tools made in the Mousterian tradition commonly associated with Neanderthals.

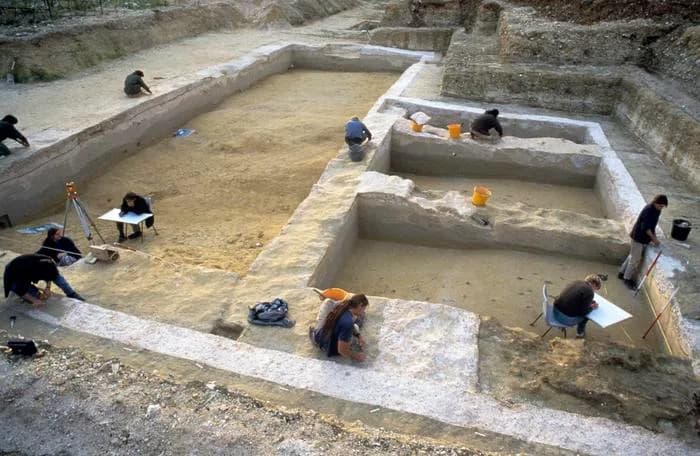

“At first glance, the deposit appears chaotic,” said Lucía Villaescusa Fernández, a doctoral researcher in archaeology at the University of Alcalá and the study’s lead author. “What initially looked like a disorganised accumulation of materials turned out to preserve a clear record of both geological processes and human activity.”

The cave experienced multiple rockfalls in the millennia after its use. Villaescusa Fernández and her team carefully mapped the precise locations of all finds and compared the distribution of rockfall debris with the placement of skulls, other bones and stone tools. Their spatial analysis showed that the skulls were not simply the result of natural collapse or water transport: the bones appear to have been purposefully positioned in specific parts of the chamber.

Although dating resolution cannot fix the duration of every event, the researchers conclude that the skull placements occurred intermittently across especially cold intervals spanning roughly 135,000 to 43,000 years ago. The repeated placement of skulls in particular zones suggests a behaviour maintained across generations rather than a one-off or purely economic activity.

Exactly why Neanderthals amassed and arranged these skulls in a chamber they do not appear to have inhabited remains unknown. The deliberate selection, handling and spatial organization of horned and antlered skulls imply cultural practices not directly linked to subsistence, with implications for how researchers view Neanderthal traditions and cultural transmission.

“Too often, discussions of Neanderthal symbolism rely on fragile evidence or optimistic interpretations,” said Ludovic Slimak, an archaeologist at the University of Toulouse who was not involved in the study. “Here, the authors take a more grounded approach, testing whether the spatial organization of the remains could be explained by natural processes alone.”

The study, published Jan. 3 in the journal Archaeological and Anthropological Sciences, adds a robust data point to the ongoing debate about Neanderthal cognitive and cultural capacities. Instead of asking whether Neanderthals were "symbolic like us," researchers are increasingly exploring what meaningful behaviours Neanderthals developed on their own terms — and this site suggests their worlds of meaning could have been organized very differently from those of Homo sapiens.

Help us improve.