The uncontrolled re‑entry of a 7.5‑tonne Zhuque‑3 upper stage briefly threatened parts of the UK before splashing down harmlessly in the Pacific. The event highlighted the growing threat from orbital debris — more than 10,000 tonnes and tens of thousands of tracked objects — and rising collision risks that could trigger Kessler Syndrome. Emerging removal projects from Astroscale and ClearSpace offer promising responses, but they also raise security and policy challenges that require international coordination.

Space Debris Near‑Miss: How a Zhuque‑3 Re‑Entry Exposed a Growing Orbital Crisis

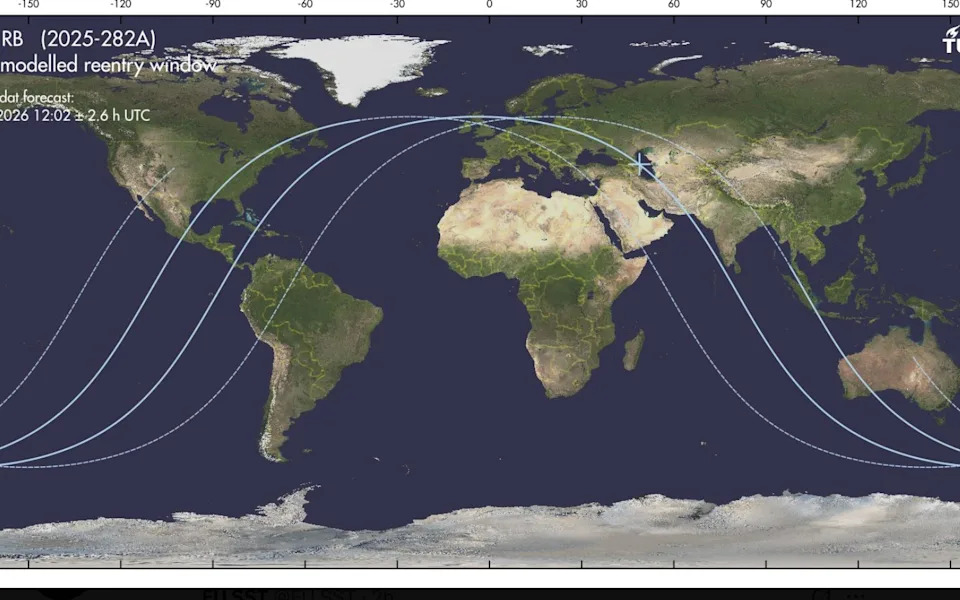

When Sir Keir Starmer travelled to Beijing earlier this week, he could not have predicted that, within days, a spent Chinese rocket stage might threaten parts of the UK. A 7.5‑tonne upper stage from a Zhuque‑3 reusable launcher briefly faced an uncontrolled re‑entry that raised concern it could fall on northern England or Scotland.

By Friday afternoon authorities reported the booster had come down without incident, splashing into the Pacific roughly 1,200 miles south‑east of New Zealand. Nevertheless, the episode prompted the UK Government to ready mobile emergency alert networks — an alarm that, if used, would have been unprecedented in Britain.

Why This Happened

The object was the top section of the Chinese rocket launched in December. Most small fragments of space junk burn up on re‑entry; larger, tougher pieces generally fall into oceans or uninhabited regions. The Zhuque‑3 stage, however, followed an orbital inclination of about 57° to the equator, meaning its ground track crossed densely populated regions in Europe, Russia and the eastern United States. That raised global concern because predicting an exact impact point for uncontrolled re‑entries is difficult until the last hours.

Who Was Watching

The EU’s space surveillance and tracking agency described the stage as a “quite a sizeable object” and monitored the re‑entry closely. Britain’s National Space Operations Centre (NSpOC) at RAF High Wycombe also tracked the object and coordinates with government response teams when re‑entries could pose a risk.

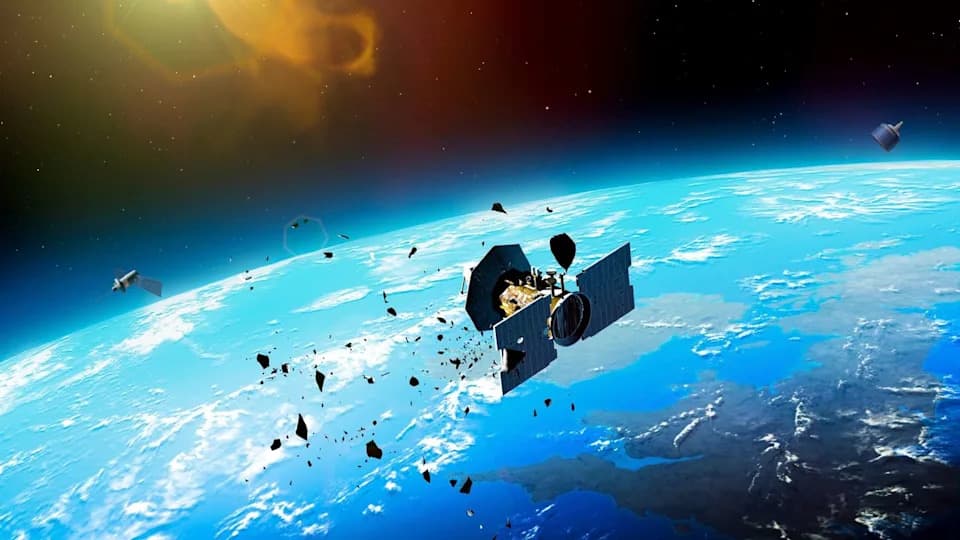

The Bigger Problem: Growing Space Junk

This near‑miss underlines a broader, escalating problem. There are already more than 10,000 tonnes of debris in orbit, and thousands of new satellites are planned or authorised for low Earth orbit. Parts of satellites or rocket bodies re‑enter the atmosphere on average more than three times a day, with larger pieces reaching the surface roughly once a day.

Risk Statistics: A 2023 study estimated a 2.3% chance that falling space debris could kill or injure at least one person, and the risk is rising year‑on‑year. NSpOC now monitors the uncontrolled re‑entry of over 870 objects annually, triggering roughly five alerts per month to UK response teams.

Kessler Syndrome And The Cascade Risk

NASA scientist Donald Kessler warned in 1978 that collisions in low Earth orbit could trigger a chain reaction: each breakup creates more fragments that increase the odds of further collisions. If such a cascade occurred — the so‑called Kessler Syndrome — it could render some orbital zones effectively unusable and cripple satellite services we rely on daily.

Current estimates put the count at about 140 million fragments smaller than 1 cm and more than 54,000 tracked objects larger than 10 cm. Meanwhile, filings and approvals for constellations number in the hundreds of thousands: SpaceX already operates roughly 11,000 Starlink satellites and has announced plans for many more.

Responses And Solutions

There are early efforts to tackle the problem. UK company Astroscale plans active debris‑removal missions and is working with the UK Space Agency, the European Space Agency and Airbus on the COSMIC (Cleaning Outer Space Mission Through Innovative Capture) project to remove two defunct British satellites. Switzerland’s ClearSpace, in cooperation with ESA, also plans a rendezvous‑and‑capture mission.

If these missions succeed, they could pave the way for fleets that remove debris, refuel and service satellites — and potentially launch from UK spaceports once they are operational. In its first year, NSpOC issued roughly 30,000 collision warnings to UK‑licensed satellite operators, demonstrating the urgency and scale of active traffic management in orbit.

Security Concerns

However, debris‑cleaning technology raises geopolitical and security questions. Systems capable of grappling objects in orbit could, in the wrong hands, be repurposed to seize or disable operational satellites. Observers have noted instances of Russian satellites loitering near communications platforms and Chinese spacecraft conducting close, provocative manoeuvres.

The trade‑off is clear: the world must remove hazardous debris to protect orbital access and life on Earth, but must also set strong norms and transparency to prevent weaponisation of removal technologies.

Conclusion

The Zhuque‑3 incident was a lucky escape, but it served as a vivid reminder that increasing congestion in low Earth orbit has real, immediate consequences. International cooperation, better tracking, responsible satellite design and active removal missions will all be needed to prevent future close calls — and to keep space safe and useful for everyone.

Help us improve.