Space debris re-entering Earth’s atmosphere poses a small but increasing risk to aircraft as launches and satellite constellations grow. Recent studies estimate a roughly 26% chance that uncontrolled debris will cross busy airspace within a year and project an individual-flight strike probability approaching 1 in 1,000 by 2030. Experts call for better measurements, improved re-entry models (including ESA’s DRACO mission), and international standards and coordination so airspace closures can be precise and proportionate.

Rising Risk: Falling Space Debris Could Threaten Airliners — What Experts Recommend

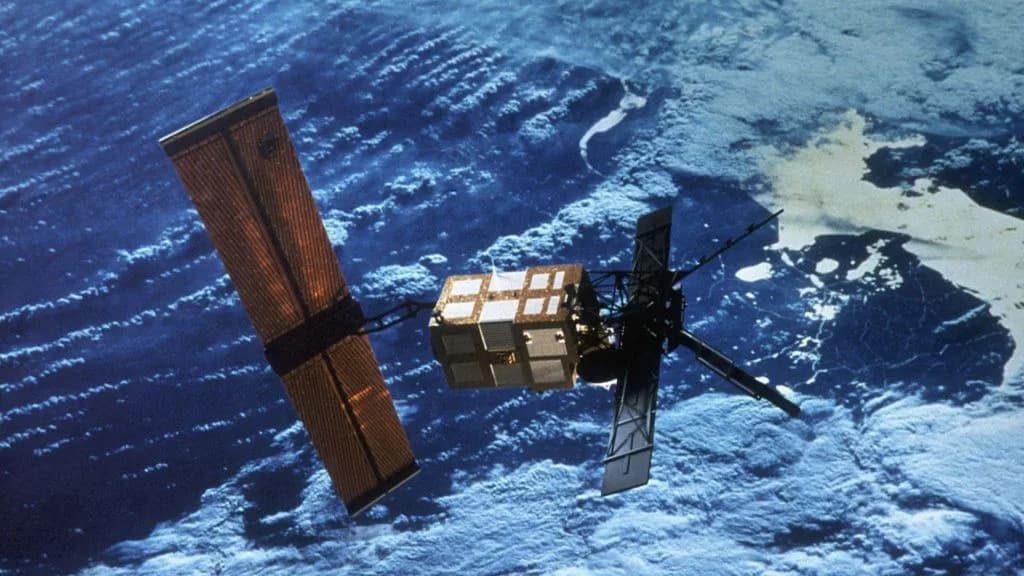

Space debris is no longer just an orbital problem. As more rockets launch and larger satellite constellations populate low Earth orbit, objects falling back through the atmosphere are becoming more frequent — and the small but growing risk they pose to aircraft is attracting attention from regulators and researchers.

How Often Debris Falls—and Why It Matters

On average, about one spacecraft or a significant spacecraft component re-enters Earth's atmosphere each week. Most of these objects — spent rocket stages or defunct satellites — burn up or break apart at high altitude. But fragments ranging from fine particles to whole tanks can survive long enough to reach altitudes where commercial aircraft operate (about 30,000–40,000 feet / 9,144–12,192 meters).

A University of British Columbia paper published in early 2025 estimated roughly a 26% chance that, within the coming year, some uncontrolled re-entry will pass through one of the world’s busiest airspace corridors. A separate 2020 study projected that by 2030 the probability that any single commercial flight could be struck by falling debris might approach 1 in 1,000. The absolute risk to any given passenger remains very low, but because aircraft carry many people and certain small fragments can disable engines, even a rare strike could have severe consequences.

Notable Incidents and Near Misses

A high-profile case occurred in November 2022, when the roughly 20‑ton core stage of a Chinese Long March 5B rocket made an uncontrolled re-entry whose ground track crossed Spain. Spanish authorities closed a corridor roughly 100 kilometers on either side of the path for about 40 minutes, affecting more than 300 flights; the debris itself occupied the restricted airspace for only a few minutes. A separate re-entry of a SpaceX vehicle over Europe in summer 2025 also led to temporary airspace restrictions. So far there has been no catastrophic strike on a commercial airliner, but experts warn that preparation is essential.

Why Predicting Re-Entry Is Hard

Accurately forecasting where and when an uncontrolled spacecraft will re-enter is still extremely challenging. The upper atmosphere — roughly the 100–200 kilometer region where objects begin to experience significant drag — is poorly sampled and highly variable. Small changes in solar activity, atmospheric temperature, or orientation of the re-entering object can shift predictions by hours and thousands of kilometers of ground track. That level of uncertainty forces aviation authorities into a difficult trade-off: either accept a small risk to people or issue broad airspace closures that disrupt flights and cost millions.

What Experts Want: Better Data, Models and Coordination

Researchers and agencies are pursuing several complementary approaches to reduce both actual risk and unnecessary disruption:

- Better data and models: Missions and exercises to collect re-entry measurements will improve predictions of breakup altitude, fragment survivability and impact footprints.

- Targeted operational thresholds: Aviation regulators will need clear, internationally coordinated standards defining when to issue airspace restrictions based on probability and expected fragment sizes.

- Improved coordination: Faster, routine communication between space surveillance organizations, launch providers and national/ICAO air-traffic authorities will enable narrower, more precise closures.

- Design mitigation: Encouraging satellite and rocket-stage designs that disintegrate more completely at high altitude will reduce the amount of debris that reaches flight levels.

Ongoing Efforts

Two programs promise to deliver much-needed data. The European Space Agency's DRACO (Destructive Re-entry Assessment Container Objective), planned for late 2027, will carry roughly 200 sensors to record precisely how a small test capsule and instrumented components break apart during re-entry. DRACO is designed to be destroyed; a data recorder will descend by parachute to preserve the measurements. Meanwhile, the Inter-Agency Space Debris Coordination Committee (IADC) runs annual Re-Entry Campaigns in which member agencies compare forecasts against real outcomes to refine models and procedures.

"What we are trying to investigate is the threshold for risk for an aircraft — at what risk should we react?" — Benjamin Virgili Bastida, ESA space debris systems engineer

What This Means For Travelers

Experts stress that the probability an individual passenger will be struck by space debris is extremely low — far lower than many everyday risks. However, the aviation and space communities are working to make re-entry predictions more accurate and responses more proportionate so that future disruptions are targeted and minimal. In time, narrowly defined, short-lived reroutes or brief airspace closures may become as routine as weather-related delays, with little notice to most travelers.

Bottom line: The risk is small but rising. Improved measurement (DRACO), international exercises (IADC), model development and agreed operational thresholds are the tools that will let authorities manage safety without crippling air traffic.

Help us improve.