Researchers demonstrated that networks of seismometers can detect sonic booms from reentering space debris, enabling near-real-time tracking. The method was validated on a Shenzhou-15 fragment that fell in April 2024 and reported in Science. As low Earth orbit fills with short-lived satellites from mega-constellations, reentries are now daily events in some regions — increasing risks to aircraft, people, infrastructure, and atmospheric chemistry. Seismic, infrasound and radar sensors together can speed recovery and provide independent data on reentry behavior.

Seismometers Track Falling Space Junk: Real-Time Detection of Sonic Booms From Reentry

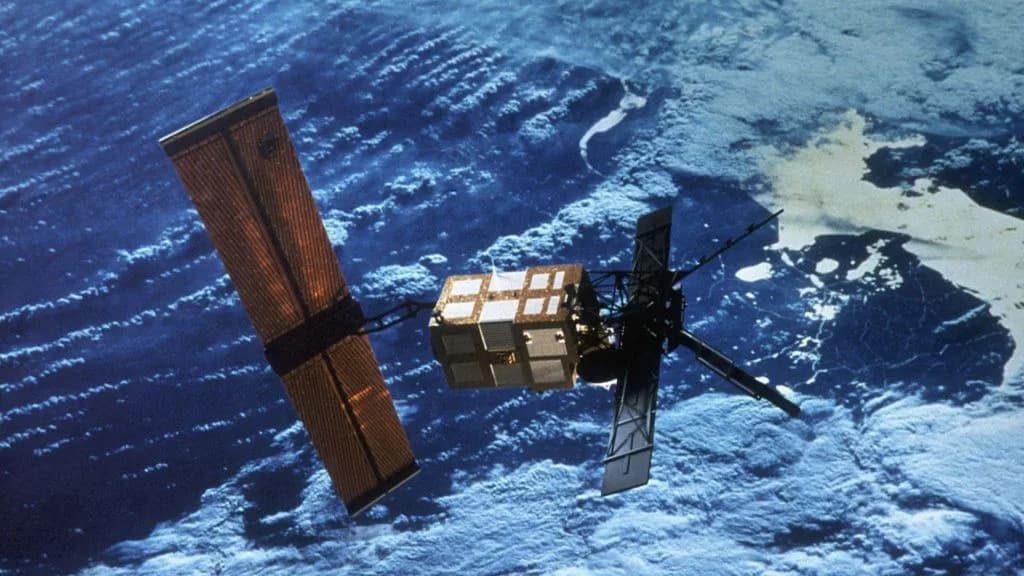

Last February, fragments from a SpaceX Falcon 9 rocket lit up skies across Europe before striking the ground in Poland and damaging a village warehouse. A month later the uncrewed trunk of a SpaceX vehicle landed in the Sahara Desert. In May, the Soviet-era Kosmos 482 — a Venus probe launched in 1972 — broke apart during reentry, most likely over the Indian Ocean west of Jakarta.

Using Earthquake Sensors To Follow Reentering Debris

These events remain uncommon but are occurring more frequently as low Earth orbit fills with short-lived satellites and large constellations such as Starlink. Most debris burns up on reentry, and surviving pieces usually fall into oceans, deserts, or sparsely populated areas. Still, the growing cadence of reentries raises rising risks to aircraft, people, infrastructure and the composition of the atmosphere.

Researchers Benjamin Fernando (Johns Hopkins University) and Constantinos Charalambous (Imperial College London) recently showed that networks of seismometers — instruments normally used to detect earthquakes — can pick up the shock waves (sonic booms) produced by large fragments as they streak through the atmosphere. They validated the method on a piece of debris from Shenzhou-15 that fell in April 2024 and published their results in Science.

Why Seismic Networks Work

When a fast-moving object creates an atmospheric shock, part of that energy couples into the ground and is recorded by seismometers. These instruments can therefore detect both the sonic boom and any subsequent ground impact. Dense arrays (10+ stations) allow triangulation of trajectory and speed; even single stations can produce useful detections in regions with sparse coverage.

"We now see multiple satellites reentering the atmosphere every day," Fernando said. "Each reentry presents some risk to aircraft, people on the ground, and infrastructure — and the returning material is beginning to alter atmospheric composition."

Capabilities, Limits And Complementary Sensors

The technique works best where seismic networks are dense (for example, much of the contiguous United States, parts of Europe and Australasia). In regions with fewer seismometers, infrasound sensors (used for nuclear monitoring) can detect atmospheric shock waves directly, and weather radars frequently register reentry trails and fragments. Military radars offer even greater coverage but are typically classified and not available for open scientific study.

Seismic and atmospheric sensors are complementary: combined they improve trajectory estimates, fragment characterization and the speed of post-impact response — critical for recovering hazardous debris and validating industry claims about complete disintegration on reentry.

Risks, Examples And Environmental Concerns

Reentries are becoming more common because mega-constellations deploy thousands of low-orbit satellites with short operational lifetimes. Prediction is difficult: below roughly 200 km altitude, aerodynamic forces become chaotic and small changes can produce very large deviations, so forecasted impact zones often remain highly uncertain until very close to reentry.

Some components are more likely to survive reentry and cause ground hazards: dense, structurally robust parts such as fuel tanks, battery packs, and (rarely) nuclear reactors. The worst historical incident was Kosmos 954 (1978), a Soviet reconnaissance satellite with a nuclear reactor that scattered radioactive debris over northern Canada and left substantial cleanup challenges.

There are also atmospheric and environmental concerns. High-temperature breakup releases black carbon (a warming agent), nitrogen species and volatile organics that may affect ozone chemistry, and heavy metals and other pollutants whose impacts in the upper atmosphere are not well understood.

What Seismology Can — And Can’t — Do

Seismic detection is primarily a near-real-time tracking and response tool. It helps locate where debris landed so recovery teams can act quickly and independent researchers can evaluate industry claims about satellite disintegration. However, intercepting or diverting falling debris in flight is effectively impossible with current tools: fragments travel faster than the speed of sound and will impact long before a sonic boom is heard on the ground.

Better, open-source observational data (from seismometers, infrasound, radar and public atmospheric sensors) is essential to assess risks, guide cleanup, and quantify potential effects on the atmosphere. Whether that data comes from public release of classified sources or broader deployment of monitoring networks remains an open policy question.

Bottom Line

Seismometer networks provide a novel, cost-effective way to detect and track large pieces of space debris during reentry. While they can’t stop falling fragments, these sensors significantly improve our ability to locate, recover, and study hazardous debris — a capability that will become increasingly important as low Earth orbit becomes more crowded.

Help us improve.