The study demonstrates that existing earthquake‑monitoring networks can detect sonic booms from reentering space debris and reconstruct trajectories. Using data from 127 seismic stations in California, researchers traced a 1.5‑ton module from China's Shenzhou 17 and found its path about 25 miles (40 km) north of U.S. Space Command predictions. While not predictive, the method rapidly pinpoints impact zones to accelerate hazardous‑debris recovery and improve estimates of what survives reentry. The research was published Jan. 22 in Science.

Earthquake Sensors Pinpoint Space Junk Reentries by Listening for Sonic Booms

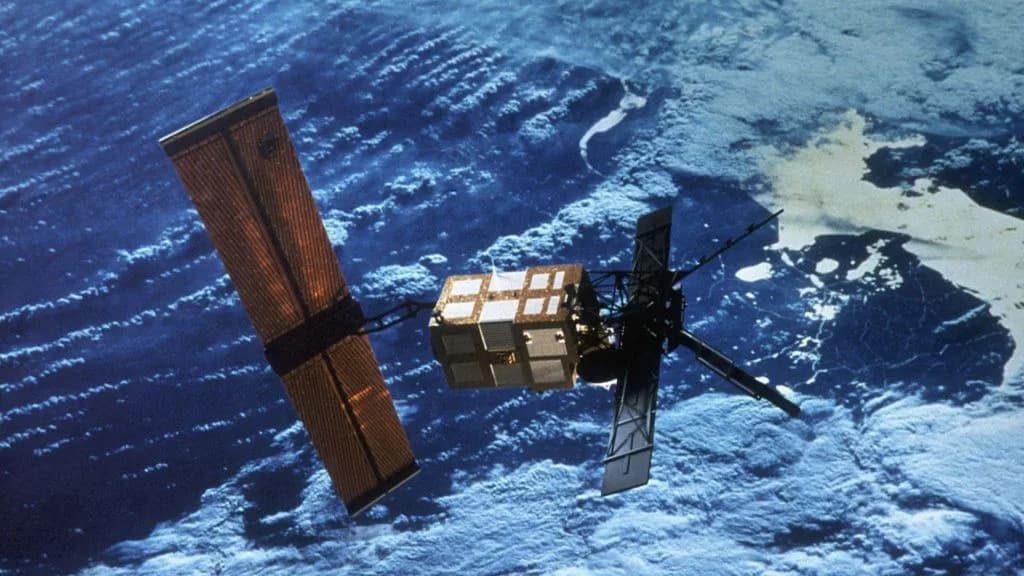

At least three sizable pieces of orbital debris — including defunct satellites and spent rocket stages — fall back toward Earth every day on average, yet researchers still lack a clear picture of where fragments land and how they break up in the atmosphere. A new technique uses sonic‑boom detections recorded by networks of earthquake sensors to reconstruct reentry paths in near real time, improving search and recovery and helping to assess ground risk.

Tracking Reentries with Seismic Networks

The method, developed by teams at Johns Hopkins University and Imperial College London, takes advantage of the dense, publicly available array of seismic stations that already monitor tectonic activity around the globe. These sensors pick up not only earthquakes but also explosions, vehicle traffic and other airborne disturbances — including the sonic signatures of supersonic objects reentering Earth's atmosphere.

In April 2024, the researchers applied the technique to an orbital module that separated from China's Shenzhou 17 crew capsule. The detached 1.5‑ton module was expected to reenter over the South Pacific or North Atlantic, but seismic analysis told a different story.

"The space situational awareness radars and optical tracking are great when the object's in orbit," said Benjamin Fernando, a postdoctoral fellow at Johns Hopkins University and the study's lead author. "But once you're below a couple of hundred kilometers, interactions with the atmosphere become quite chaotic, and it's not always apparent where the piece of debris will re‑enter."

The team analyzed data from 127 seismic stations across California to trace the sonic boom produced as the module hurtled through the atmosphere at speeds reaching roughly 30 times the speed of sound. Their reconstruction showed the sonic signature passing about 25 miles (40 km) north of the trajectory predicted by U.S. Space Command and suggested fragments could have fallen somewhere between Bakersfield, California, and Las Vegas, Nevada.

What This Adds to Space‑Traffic Awareness

While seismic detections cannot forecast where an object will land before it happens, they can rapidly identify where pieces have already come down — shrinking search times from days or weeks to hours or minutes. That speed is important for locating potentially hazardous fragments (for example, fuel tanks or batteries), protecting public safety and retrieving debris that could pose environmental or radiological risks.

"A supersonic object will always outrun its own sonic boom," Fernando said. "You're always going to see it before you hear it. If it's going to hit the ground, there's nothing we can do about that. But we can try to reduce the time it takes to find fragments from days or weeks down to minutes or hours."

The researchers note that seismic stations convert ground vibration into electrical signals and can detect sonic booms from hundreds of miles away. They also point to acoustic sensor networks — which detect infrasound and other atmospheric acoustic waves — as a complementary resource that could extend coverage, especially over oceans where seismic stations and radars are sparse.

Fernando highlighted that acoustic networks have recorded distant events such as rocket launches from thousands of miles away — for example, sensing Starship launches from Texas as far away as Alaska — and could help verify where reentries occur over open ocean, addressing claims that some satellites fully vaporize on reentry.

Broader Implications

Beyond helping emergency response, this approach can improve estimates of how much debris actually survives reentry. Companies such as SpaceX say many small satellites vaporize on reentry, but experts worry that resilient components (like tanks and batteries) may survive. Better empirical tracking will inform risk assessments for people, property and aircraft.

The study was published Jan. 22 in the journal Science.

Help us improve.