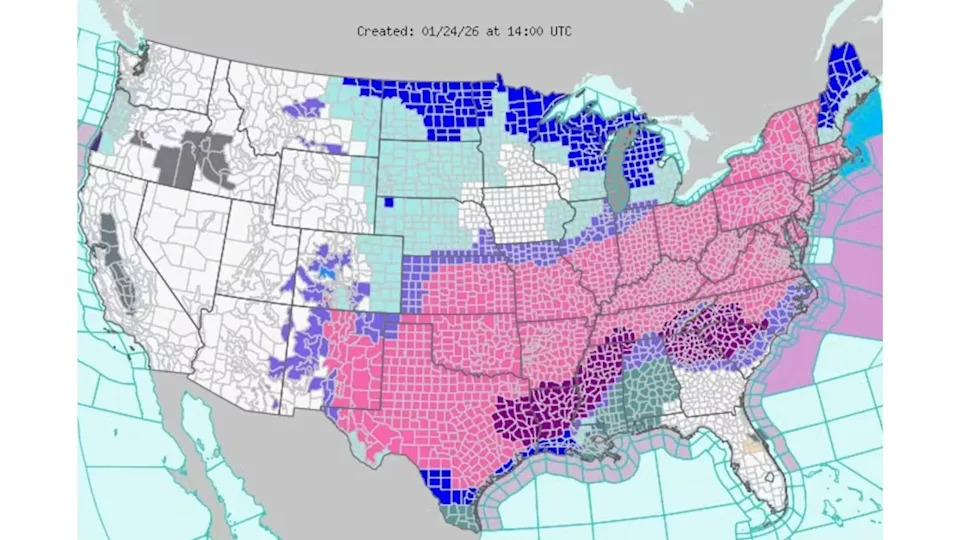

The late‑January 2026 storm brought widespread freezing rain, sleet and heavy snow from New Mexico to New England, cutting power for hundreds of thousands and dumping more than a foot of snow in parts of the Midwest and Northeast. Forecasters say the storm resulted from a southward plunge of Arctic air and a displaced stratospheric polar vortex that amplified jet-stream swings, while warm Gulf waters supplied abundant moisture. Climate change may be making such polar-vortex disruptions and extreme precipitation events more likely, even as average snowfall trends change.

How a Displaced Polar Vortex and Warm Gulf Waters Supercharged the Late‑January 2026 U.S. Winter Storm

A powerful winter storm in late January 2026 dropped freezing rain, sleet and heavy snow across a broad swath of the United States, from New Mexico to New England. Hundreds of thousands of people lost power as ice-laden branches and power lines collapsed, parts of the Midwest and Northeast recorded more than a foot of snow, and bitter cold was expected to linger for days.

What Happened

The event followed a generally mild start to the season. Paradoxically, that earlier warmth helped set the stage: very warm ocean waters supplied abundant moisture, while a strong Arctic air mass plunged southward, creating a sharp temperature contrast. Multiple disturbances within the jet stream combined to produce strong lift and precipitation, and the storm tapped plentiful moisture from the unusually warm Gulf of Mexico.

How the Polar Vortex and the Jet Stream Interacted

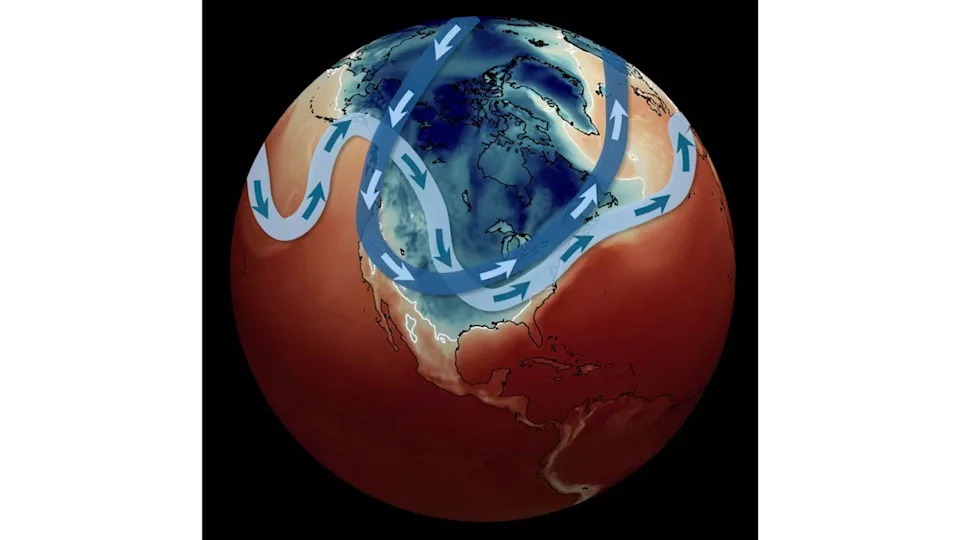

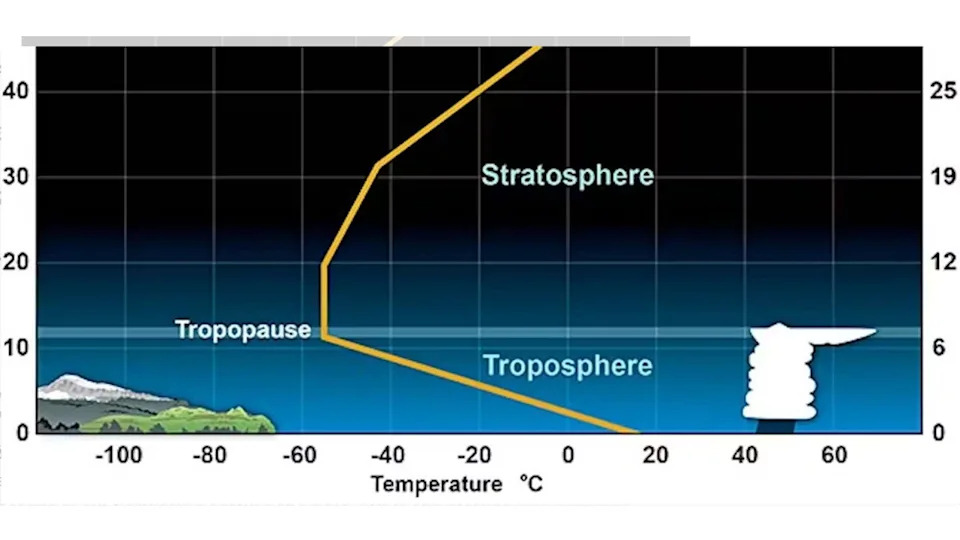

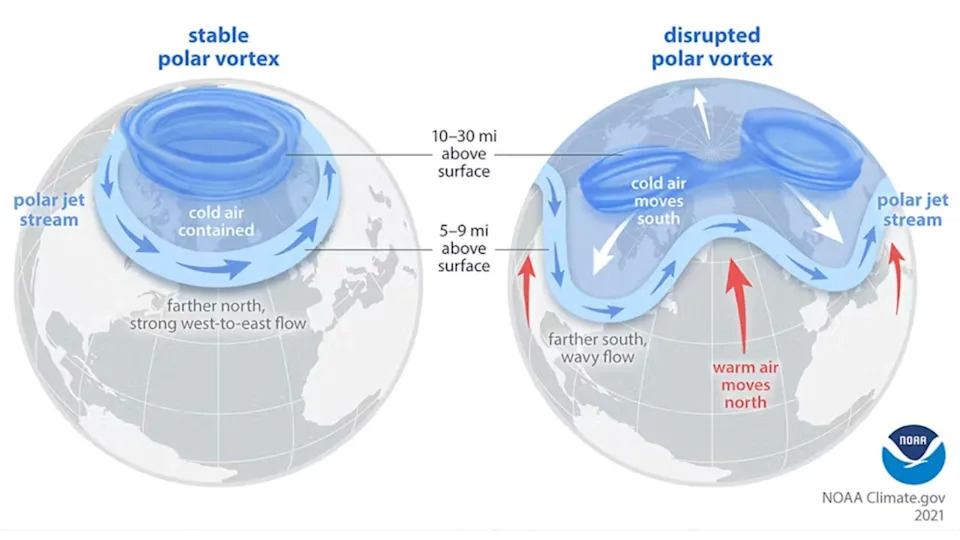

The jet stream—the fast ribbon of air that steers mid-latitude weather—typically has its strongest winds just below the top of the troposphere, roughly seven miles above the surface. Above that lies the stratosphere, extending to about 30 miles. Although the stratosphere sits well above everyday weather, it can interact with the troposphere through vertically propagating atmospheric waves.

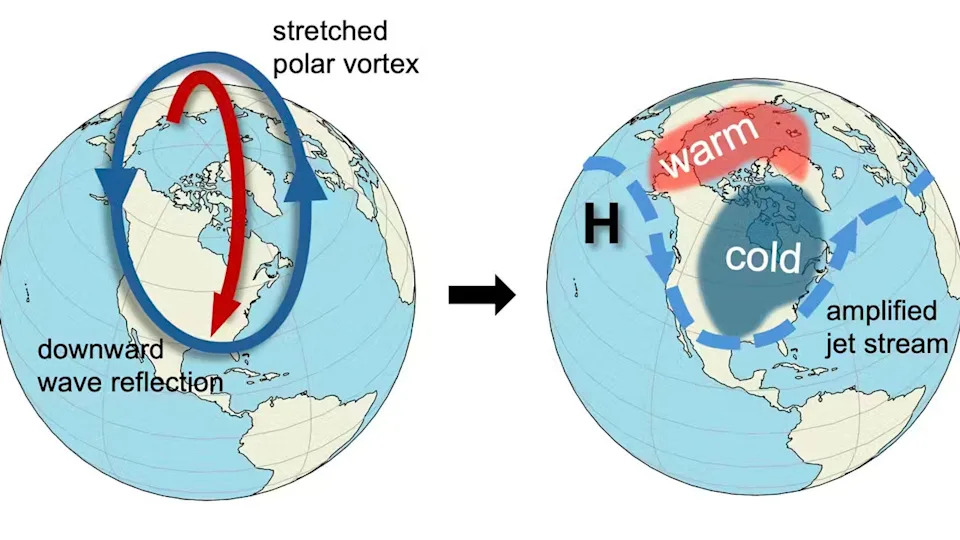

"Polar vortex" is often used to describe cold air pushing south, but it actually refers to two related circulations: one in the troposphere and a separate one in the stratosphere. The Northern Hemisphere stratospheric polar vortex is a fast-flowing belt of air circling the pole. Occasionally it displaces or stretches southward, which enhances vertical wave activity that can then amplify north-south swings in the tropospheric jet stream.

Forecasts for the January event showed a strong overlap between a southward-reaching stratospheric polar vortex and a deep trough in the tropospheric jet stream over the United States. Energy reflected off the displaced polar vortex propagated back into the lower atmosphere, intensifying jet-stream undulations and increasing the odds of severe winter weather across the central and eastern U.S.

Role of the Warm Ocean and Moisture

Warmer ocean temperatures increase evaporation, loading the atmosphere with moisture. A warmer air column can hold more water vapor, and when that moisture condenses into rain or snow it releases latent heat that can energize storms. At the same time, long-term warming tends to reduce temperature contrasts in some regions, which can weaken certain storm dynamics. In this case the abundant Gulf moisture helped the system produce heavy snow, sleet and damaging ice.

Climate Context

Earth is unequivocally warming as human activities increase greenhouse gases, and overall snow amounts are trending down in many regions. But warming does not eliminate the possibility of severe winter storms.

Some research suggests that while cold outbreaks may become less frequent on average, they can remain intense in certain locations. Rapid Arctic warming appears linked to more frequent disruptions of the stratospheric polar vortex, which can increase the chance of amplified jet-stream patterns and extreme winter weather. Meanwhile, the additional moisture available in a warmer world may favor heavier precipitation events, even if the form of precipitation (snow versus sleet/freezing rain) changes in many areas.

Forecasting and Research

Scientists continually improve models and observations to better predict such events, but important questions remain. Much of the modeling, instrumentation and long-term data that forecasters depend on come from federal research programs and government laboratories such as the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR). Proposed funding cuts and political pressure on these institutions could hinder the development of tools and the long-term records that underpin reliable forecasts.

Bottom line: The late‑January storm was the result of a rare alignment of factors—an Arctic air mass, a southward-reaching stratospheric polar vortex that amplified jet-stream swings, and unusually warm Gulf waters that supplied moisture. These interactions produced heavy snow, widespread ice and prolonged cold across much of the United States.

By Mathew Barlow, Professor of Climate Science, UMass Lowell, and Judah Cohen, Climate Scientist, Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT)

Help us improve.