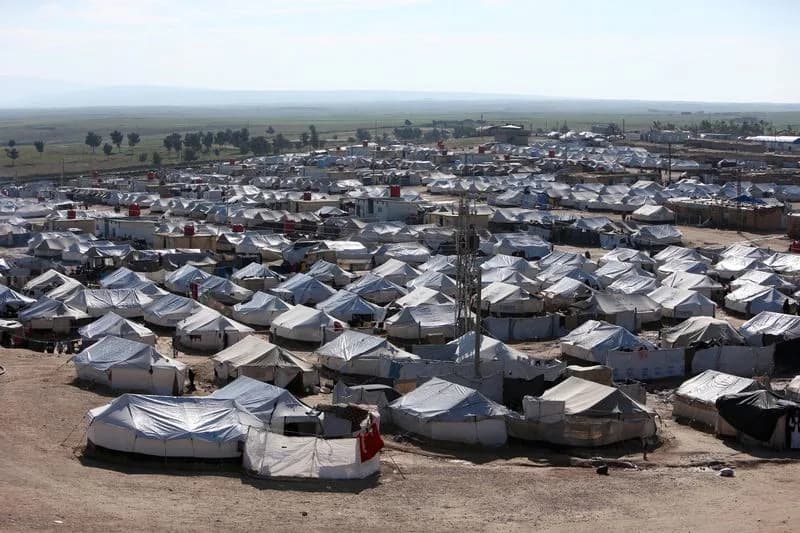

The reporter visited Al‑Roj, a northeastern Syrian detention camp holding more than 2,000 women and children linked to ISIS, where many detainees say they have been stripped of citizenship and plead for repatriation. Several interviewees insisted they no longer support ISIS and described dire conditions and fear for their children. Regional power shifts and recent security incidents have increased concerns about escapes, violence and large‑scale transfers of detainees to Iraq. The situation leaves thousands in legal limbo and heightens tensions for camp staff and local authorities.

“Utterly Stateless”: Inside Al‑Roj — A Detention Camp of Displaced Women and Children Linked to ISIS

We stepped from the biting cold into a tent at Al‑Roj, a detention camp in northeastern Syria, entering through a flimsy plastic flap that served as a door. It was warmer inside, but the weak light that seeped through the seams left faces and shadows indistinct.

A woman called out in English, "Come in! Come in." Two children — a girl and a boy — darted around, speaking in a mix of English and unusually formal Modern Standard Arabic, a register that felt out of place in an informal setting.

Al‑Roj is run by Kurdish-led authorities and holds more than 2,000 women and children — many foreign nationals and in several cases widows of men who joined the Islamic State (ISIS). Some detainees have lived in the camp for years, and many report profound legal and humanitarian uncertainty.

Stateless and Desperate

In the tent a woman with a British accent warned, "Journalists? Please no pictures!" She asked to remain anonymous, saying Britain had revoked her citizenship and that identifying her could complicate efforts to secure repatriation for relatives.

"I'm scared because I'm a different person... I'm not a Daeshi. I'm no one. I'm scared for my son," she said, adding that her 9‑year‑old was regularly bullied because she was seen as disloyal to ISIS. "I was born in England. I was raised in England. We are utterly and totally stateless."

We were taken to the tent the escort identified as belonging to another well‑known former UK resident, but the occupant declined to speak.

Voices From the Camp

This was not the reporter's first contact with women associated with ISIS; in 2019, dozens of interviews across Syria and Iraq revealed a mix of reluctant followers and committed adherents. In Al‑Roj the women who agreed to be interviewed insisted they had abandoned extremist beliefs and wanted repatriation.

"I want to come back to my country," said Alma Ismailovic, from Serbia, at the camp's small market. "I want to live a normal life with my children." Alma wore a hijab rather than the niqab associated with more hardline detainees.

Other detainees expressed similar views. "There is no Islamic state," said Hanifa Abdallah, from Russia. "It's over. All that's left is us women." Camp officials say Russian nationals form the largest single nationality group in Al‑Roj, and several interviewees said their countries had refused repatriation.

Security Concerns and Regional Shifts

Our Kurdish escort warned against walking freely among tents, claiming some residents might throw stones. During this visit few people were outside because of the cold, and there were no hostile confrontations.

But the broader security picture is volatile. Since early January, Syrian government forces and allied tribal fighters have reasserted control over parts of northern Syria previously held by the SDF. The shifting front lines and new political arrangements have raised fears that camps and prisons could be destabilized.

In recent weeks there were reports that SDF units withdrew from some detention facilities under fire, and conflicting claims emerged about prisoner numbers fleeing during incidents at sites such as Al‑Shaddadi. Authorities say roughly 7,000 ISIS detainees are being moved to more secure facilities in Iraq amid these changes.

Fear, Anger and Uncertain Futures

Camp staff expressed bitter frustration. "We fought the Islamic State on behalf of the rest of the world, and now the rest of the world is turning its back on us," said one security official. Some Kurdish administrators and guards fear reprisals or renewed violence if detainees are released or if control of facilities changes hands.

Others in detention report fear for their children and a desperate wish to return home, while many governments remain reluctant to repatriate nationals from the camps. The result is an unfolding humanitarian and legal dilemma: thousands of women and children in limbo, with limited prospects for durable solutions.

Note: Some names and claims circulating about political leaders and official statements have been reported in local media and social platforms; this article avoids repeating unverified personal attributions and instead focuses on conditions, testimonies from Al‑Roj, and confirmed operational movements reported by authorities.

Help us improve.