Businesses nationwide are facing both public pressure to condemn aggressive immigration enforcement and the practical reality of ICE activity on their premises. Agents can enter public business areas without a judicial warrant, while warrants or employer consent are typically required for private spaces — a distinction now complicated by an internal ICE memo. Companies are updating protocols, training staff and conducting I-9 self-audits as unions and community groups warn that raids harm workers and local economies.

Businesses Under Fire: ICE Raids, I-9 Audits and the Pressure on Employers

From family-run cafés to national retail chains, U.S. businesses are increasingly caught between public pressure to condemn aggressive immigration enforcement and a rising number of arrests and inspections taking place on their premises as part of expanded deportation operations.

Operations, Local Impact and High-Profile Responses

In Minneapolis — where the Department of Homeland Security said it was conducting its largest operation to date — hotels, restaurants and other businesses temporarily closed or stopped taking reservations amid widespread protests. Following the shooting death of Alex Pretti by a U.S. Border Patrol agent, more than 60 Minnesota CEOs, including leaders from Target, Best Buy and UnitedHealth, signed an open letter urging “an immediate deescalation of tensions” while stopping short of explicitly naming immigration enforcement.

Videos circulated earlier this month showing federal agents detaining two Target employees in Minnesota. ICE has also detained day laborers in Home Depot parking lots, picked up delivery workers on city streets, and in a major 2023 action federal agents arrested 475 people during a raid at a Hyundai plant in Georgia.

What ICE Can—and Generally Cannot—Do On Business Premises

Public Areas: Immigration officials may enter public-facing spaces of a business without a judicial warrant — for example, dining rooms, store aisles, open lobbies and parking lots. In those areas agents can question people, seize information and make arrests.

Private Areas: Areas where people have a reasonable expectation of privacy (back offices, closed kitchens, employee-only areas) generally require a judicial warrant signed by a judge from a specified court. Judicial warrants differ from administrative warrants, which are signed by immigration officers rather than judges.

An internal ICE memo obtained by The Associated Press asserted that administrative warrants could justify forcible entry into homes when there is a final order of removal. Civil-rights attorneys say that claim departs from established precedent and raises constitutional concerns.

In practice, agents can also gain access to non-public spaces through employer consent or claim exigent circumstances (for example, when officers are in "hot pursuit").

Other Enforcement Tools: I-9 Audits And On-Site Inspections

ICE enforcement also targets employers via I-9 audits that verify workers’ authorization to work in the U.S. Attorneys report an uptick in agents appearing in person at businesses to initiate audits — sometimes arriving in tactical gear and serving Notices of Inspection on site — instead of beginning audits by mailed notices. Employers typically have three business days to respond to a Notice of Inspection, but aggressive on-site tactics can pressure companies to act quickly.

Business Rights, Responses and Preparedness

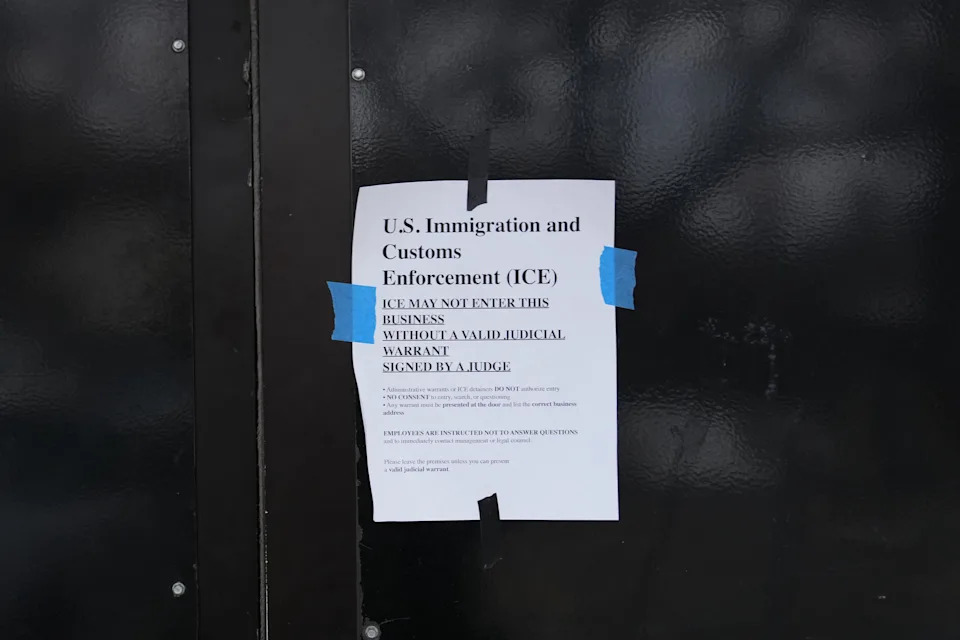

When ICE arrives without a warrant, businesses may ask agents to leave or refuse service consistent with company policy, though officers are not guaranteed to comply in public areas. Many employers are shifting their focus to documenting interactions and preparing legal challenges when they believe consent or legal requirements were violated.

In cities with increased enforcement — including Minneapolis, Chicago and Los Angeles — businesses are adopting practical measures: posting signs that mark private and employee-only areas, training staff to read and respond to different warrant types, developing response protocols, and conducting I-9 self-audits and emergency preparedness drills.

Public Reaction And Corporate Decisions

ICE’s presence and workplace arrests have provoked public outcry and pressure on companies to take public stands. Some small-business owners have spoken openly about the effects on workers and customers; some large corporations have been more guarded. Activist groups such as "ICE Out of Minnesota" have urged companies including Target, Home Depot and Hilton to publicly oppose enforcement actions occurring at their locations. Home Depot has previously denied involvement in immigration operations; Hilton did not respond to requests for comment for this story.

Labor organizations — including local chapters of the Culinary Union and the United Auto Workers — have criticized the enforcement actions as unlawful or harmful to workers and local economies. Legal advocates warn that aggressive enforcement can contribute to labor shortages and reduced foot traffic.

What Experts Say

“The general public can go into a store for purposes of shopping, right? And so can law enforcement agents — without a warrant,” said Jessie Hahn, senior counsel for labor and employment policy at the National Immigration Law Center. Hahn and other advocates emphasize the need for clear employer protocols, legal vigilance and public transparency about the economic and human impacts of enforcement activity.

Reporting note: Associated Press writers Rio Yamat in Las Vegas and Anne D'Innocenzio in New York contributed to this report.

Help us improve.