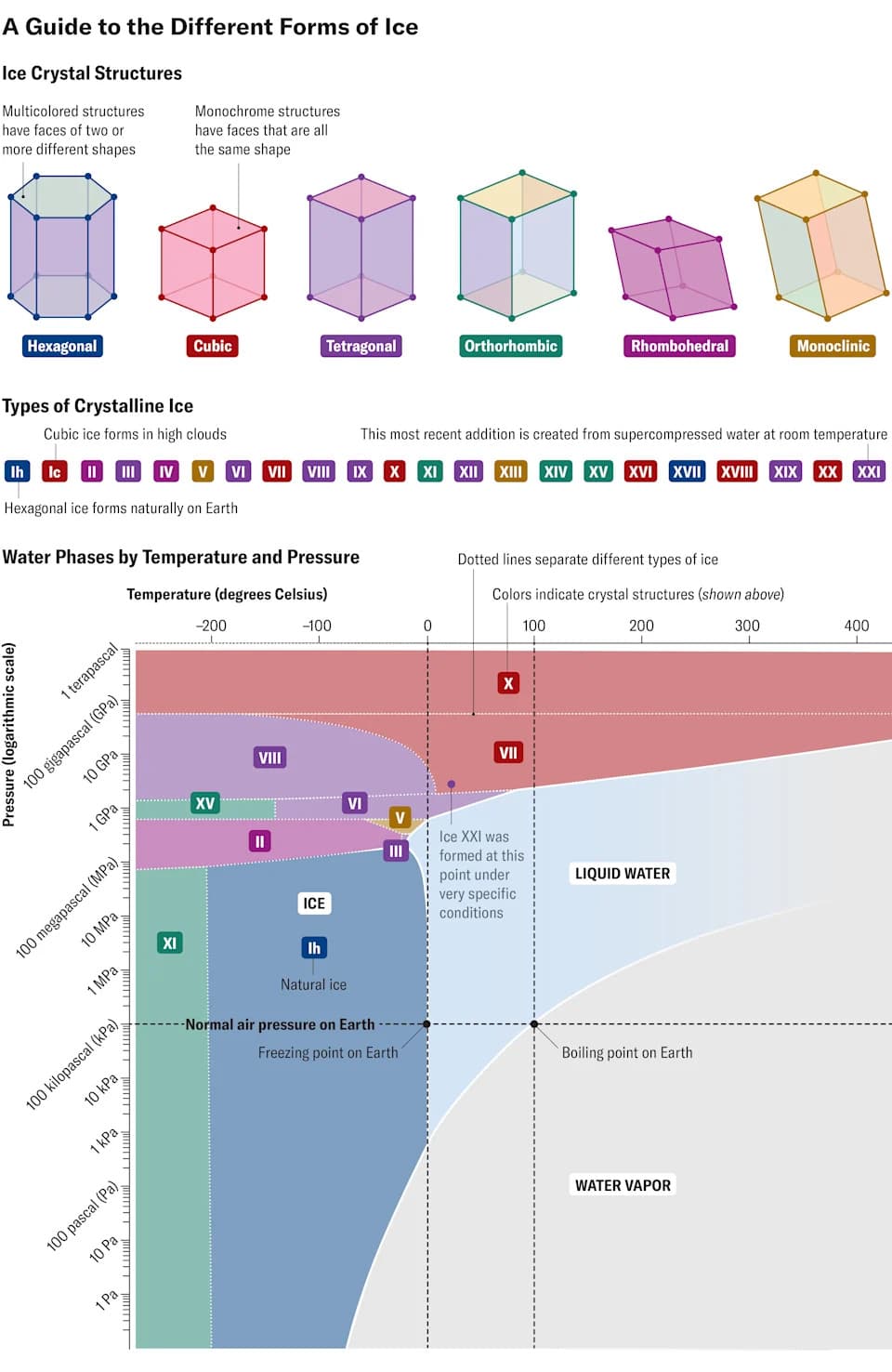

Scientists have long shown that water can freeze into many crystalline forms beyond the familiar hexagonal ice Ih. Researchers have created more than 20 distinct ice phases by subjecting water to extreme pressures, temperatures, and chemical conditions. The newly reported ice XXI is a short‑lived, blocky structure observed only with an X‑ray free‑electron laser, which adds time as an experimental variable. Some of these exotic ices may exist deep inside other planets or moons.

Scientists Reveal Ice XXI — A Fleeting, Exotic Form of Ice Revealed by Ultra‑Fast X‑Ray Lasers

Most of us only encounter one crystalline form of frozen water in everyday life: ice Ih, named for its hexagonal lattice. But under extreme conditions water can freeze into many other, far more exotic structures.

More Than 20 Known Ice Phases

For well over a century, researchers have pushed water to extreme pressures and temperatures to coax it into novel arrangements. To date, scientists have produced more than 20 distinct crystalline forms of ice—many so alien that they will never occur naturally at Earth’s surface.

The Building Block: H2O And Hydrogen Bonds

Every variety of ice, like liquid water and steam, is constructed from the same H2O molecule: an oxygen atom bonded to two hydrogen atoms at an angle of about 104.5°. In solid forms, molecules connect through hydrogen bonds—relatively weak attractions between an oxygen on one molecule and a hydrogen on another. Different arrangements of these bonds give rise to very different crystal lattices, from hexagonal and cubic to rhombohedral and tetragonal systems.

“Water is a beautiful, elegant system that consistently shows new, remarkable behavior,” says Ashkan Salamat, a physical chemist at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas. “For something so simple, it has beautiful complexity.”

How Scientists Make Exotic Ice

The hydrogen-bond network in water is extremely sensitive to temperature and pressure. Salamat describes its responses as sometimes “quantumlike,” because molecules reconfigure sharply at critical thresholds. To reach those thresholds, researchers use extreme recipes—compressing water to thousands of atmospheres or chilling it to hundreds of degrees below zero (sometimes with additives such as trace potassium hydroxide) for extended periods—to stabilize otherwise unreachable phases.

Ice XXI: A Brief, Blocky Crystal

The most recent addition to the catalog is ice XXI, reported in Nature Materials. Ice XXI forms from supercompressed water and appears as a transient, blocky crystal. Crucially, the phase was observed only by using an X-ray free‑electron laser—essentially a very high‑speed camera that captures structural changes on ultrafast timescales.

“Looking at things at a very, very fast rate allows us to observe weird and wonderful phenomena,” Salamat says, calling the laser “an incredibly exciting new toy.” By introducing time as an experimental variable alongside pressure and temperature, researchers can detect exotic ice phases that exist only for fractions of a second.

Why It Matters

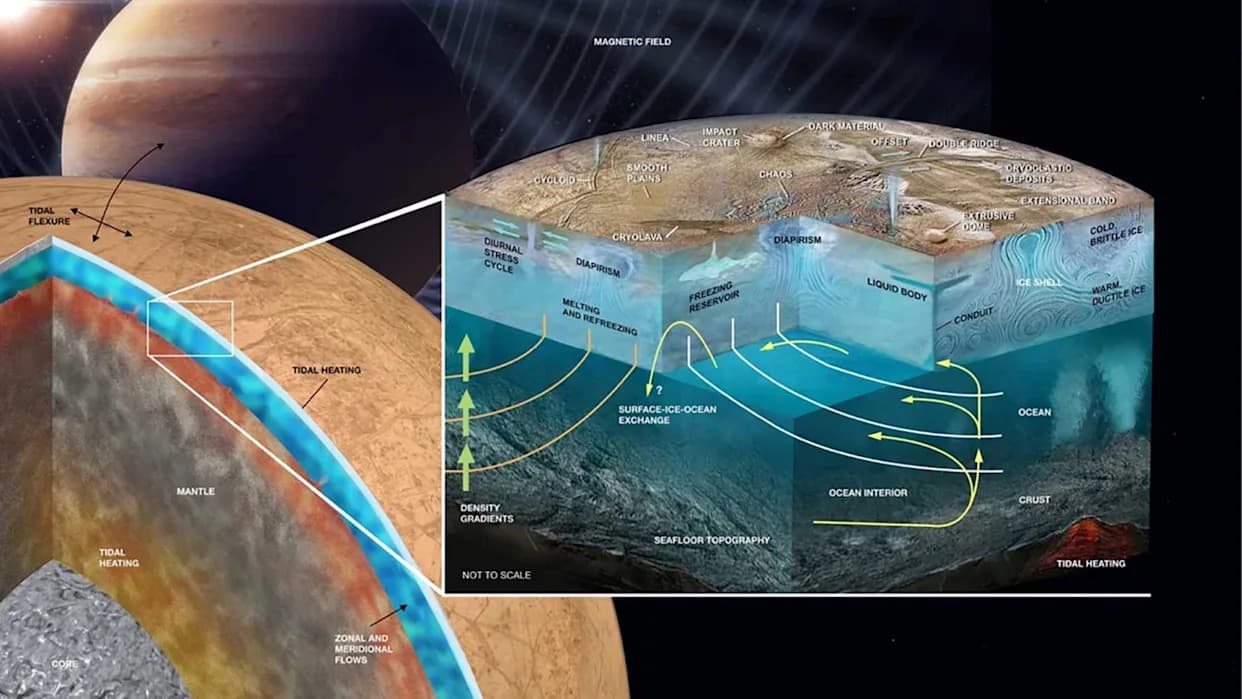

Although these unusual ice phases do not form at Earth’s surface, some may exist deep inside other planetary bodies—far beneath the clouds of Neptune, trapped inside icy moons, or in other extreme extraterrestrial environments. Beyond planetary science, discovering new ice phases advances our fundamental understanding of hydrogen bonding, crystal physics, and matter under extreme conditions.

Sources: Reporting based on Scientific American coverage and the cited Nature Materials paper; additional background from water‑structure compilations and phase diagrams.

Help us improve.