The study demonstrates that peptides can form inside icy dust grains in interstellar space when exposed to ionizing radiation, without any liquid water. Researchers cooled glycine to −436°F (−260°C) and irradiated the ice with high-energy protons, producing glycylglycine and other complex organics. The results suggest cosmic rays can drive prebiotic chemistry in cold interstellar ices, potentially delivering peptide-bearing material to forming planets.

Proteins Before Planets: How Icy Space Grains May Have Forged Life’s First Building Blocks

The chemical story that led to life on Earth may have begun far from our planet—in the cold, irradiated ices that coat interstellar dust—according to a new laboratory study. The experiments demonstrate a plausible route for amino acids to join into short peptide chains under space-like conditions, a step long thought to require liquid water.

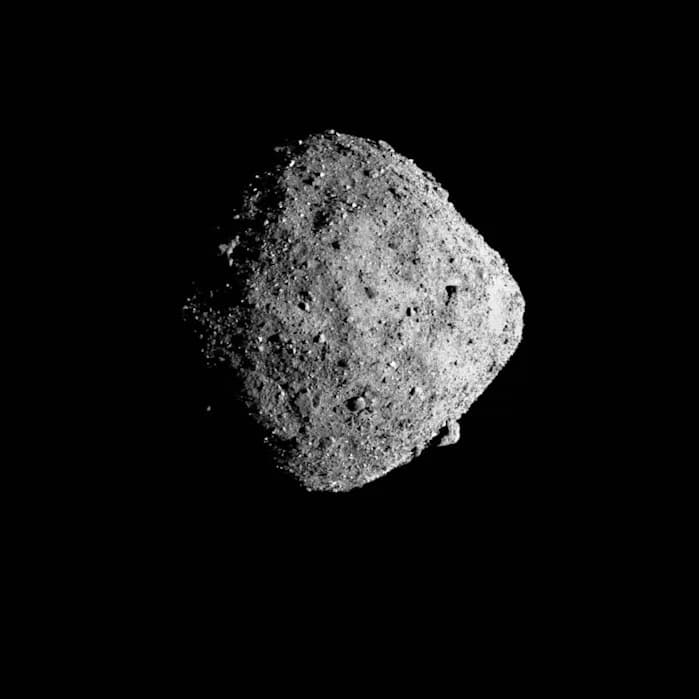

For years, astronomers have detected simple organic molecules drifting in interstellar clouds and have found related compounds preserved in meteorites and comets, suggesting that biologically relevant molecules can form in space and be delivered to planets. But a key question remained: how can amino acids link together in the extreme cold and vacuum of the interstellar medium to form peptides, the short chains that are the first building blocks of proteins?

"We already know from earlier experiments that simple amino acids, like glycine, form in interstellar space. But we wanted to discover whether more complex molecules, like peptides, could form naturally on the surface of icy dust grains before those grains participate in star and planet formation," said Sergio Ioppolo of Aarhus University.

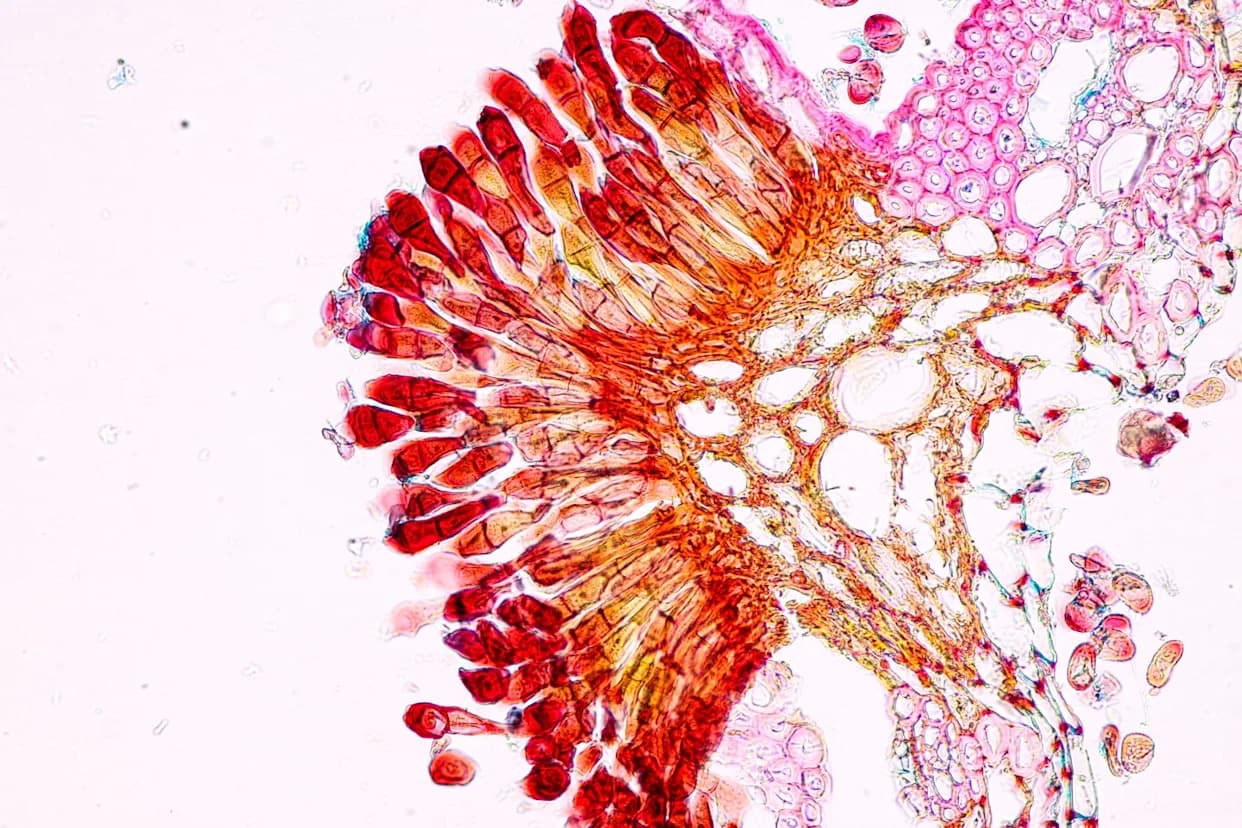

In laboratory experiments designed to mimic the icy mantles that coat cosmic dust grains, Ioppolo and colleagues cooled the amino acid glycine to cryogenic temperatures—about −436°F (−260°C)—and bombarded the frozen sample with high-energy protons as a proxy for cosmic rays. Under these conditions they detected glycylglycine, the simplest dipeptide, together with ordinary water, deuterated water (where hydrogen atoms are replaced by the heavier isotope deuterium), and a variety of other complex organic molecules.

The results reveal a previously unknown pathway for producing protein precursors that does not require liquid water. Ionizing radiation supplies enough energy to break and reform chemical bonds inside the ice, allowing amino acids trapped in the matrix to link together. In effect, cosmic rays act as a chemical engine that drives molecular complexity in regions once considered too cold and inert for such chemistry.

"All types of amino acids bond into peptides through the same reaction. It is therefore very likely that other peptides naturally form in interstellar space as well," said co-author Alfred Thomas Hopkinson, also of Aarhus University. The team plans to test additional amino acids in future experiments.

These findings broaden the range of environments where life’s precursors might arise. Rather than being confined to warm, wet settings—such as early Earth's oceans or hydrothermal vents—peptide synthesis could occur directly in the cold interstellar medium. As gas clouds collapse to form stars and planetary systems, icy grains containing peptides and other organics can be incorporated into comets, meteorites, and planetesimals, delivering complex molecules to young planets.

"Eventually, these gas clouds collapse into stars and planets. Bit by bit, these tiny building blocks land on rocky planets within a newly formed solar system. If those planets are in the habitable zone, there is a real probability that life could emerge," Ioppolo said. He added that while this research does not explain exactly how life began, it shows that many of the complex molecules necessary for life can be created naturally in space.

The study was published on Jan. 20 in the journal Nature Astronomy.

Help us improve.