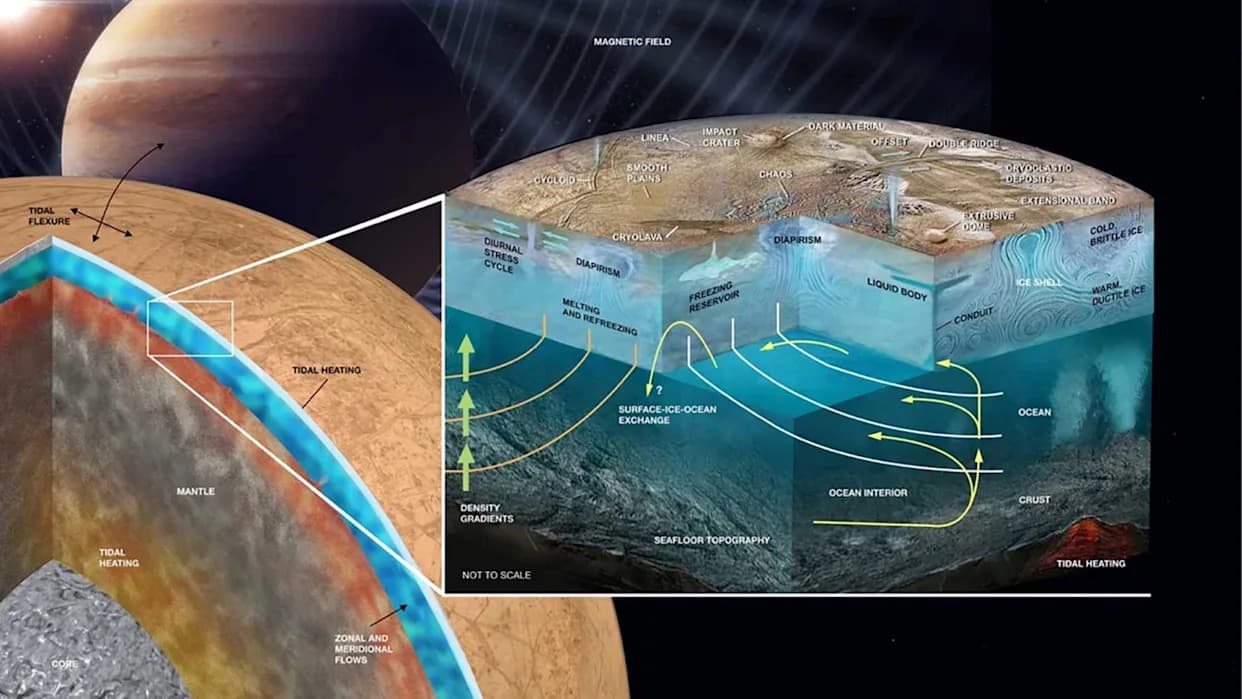

Researchers modeling Europa's ~30 km ice shell propose that salt-rich pockets near the surface can become denser and weaker, detach, and slowly sink toward the subsurface ocean. In all six modeled scenarios, material from the top ~300 m descends toward the base; sinking can begin in 1–3 million years and reach the ocean in 5–10 million years, or as quickly as ~30,000 years in heavily weakened ice. This "dripping" process — analogous to lithospheric foundering on Earth — could provide a steady pathway for surface-produced oxidants to reach the ocean and improve Europa's habitability prospects. NASA's Europa Clipper (arriving 2030) will gather data to test the idea.

Sinking Ice on Europa Could Deliver Oxidants to Its Hidden Ocean — Boosting Habitability

New research suggests Jupiter's icy moon Europa may have an overlooked, steady mechanism for transporting chemicals that could support life from its irradiated surface down to the global ocean beneath its ice shell.

Europa is a prime target in the search for extraterrestrial life because a fractured, frozen crust hides a salty ocean that may contain roughly twice the volume of Earth's oceans. Unlike Earth's sunlit, oxygenated seas, Europa's ocean is sealed from sunlight and largely depleted in oxygen, so any life there would likely rely on chemical energy rather than photosynthesis. A central question has been how oxidants produced by Jupiter's intense radiation at the surface could be delivered through Europa's thick ice shell to the ocean below.

Using computer models, researchers at Washington State University found that near-surface pockets of salt-rich ice can become both denser and mechanically weaker than surrounding, purer ice. Under favorable conditions those denser patches can detach and slowly sink — or "drip" — through the overlying ice shell, carrying surface-produced chemicals downward.

"This is a novel idea in planetary science, inspired by a well-understood idea in Earth science," said lead author Austin Green, now a postdoctoral researcher at Virginia Tech. "Most excitingly, this new idea addresses one of the longstanding habitability problems on Europa and is a good sign for the prospects of extraterrestrial life in its ocean."

Modeling The Process

The team modeled an ice shell roughly 18.6 miles (30 kilometers) thick across six scenarios spanning different damage and weakening conditions. In every scenario, material originating within the uppermost ~300 meters of the shell descended toward the base. In some runs the sinking began after about 1–3 million years and reached the shell base after roughly 5–10 million years. In simulations where the ice shell was more heavily damaged or weakened, sinking initiated much faster — in some cases after as little as 30,000 years.

An Earth Analogy

Researchers describe the mechanism as analogous to lithospheric foundering on Earth, where dense portions of the outer layer sink into the mantle. A comparable process was identified beneath California's Sierra Nevada in 2025. On Europa, the process would operate much more slowly but, according to the study, could nonetheless provide an ongoing pathway for transporting oxidants and other surface-produced chemicals down to the ocean.

Implications And Next Steps

If validated, this sinking-ice mechanism could help supply chemical energy to Europa's ocean and strengthen the moon's prospects for habitability. NASA's Europa Clipper mission, launched in 2024, is scheduled to arrive in the Jovian system in April 2030 and will perform nearly 50 close flybys of Europa. Data from Clipper — including measurements of ice-shell thickness, surface composition, and geologic activity — will help test the new model and clarify whether oxidants can indeed reach the subsurface ocean.

The team's research was published Jan. 20 in The Planetary Science Journal.

Help us improve.