New computational work suggests frozen hydrogen cyanide (HCN) crystals have reactive surfaces that can drive prebiotic chemistry. Models identify two pathways converting HCN into the more reactive hydrogen isocyanide (HNC), enabling reactions with water that produce polymers, amino acids and nucleobases. HCN and HNC are common across the Solar System (including Neptune and Titan), making those worlds compelling targets for astrobiology. The findings extend ideas from Miller–Urey experiments and recent studies linking cyanide to atmospheric carbon chemistry.

Could Deadly Cyanide Have Sparked Life? Frozen HCN Surfaces May Have Built Earth’s First Biomolecules

Hydrogen cyanide (HCN) is infamous for its toxicity, but new research suggests that when frozen its surfaces could have fostered chemical reactions crucial to the origin of life. Computer models show that HCN ice can promote pathways toward increasingly complex organic molecules even at very low temperatures.

What the study found

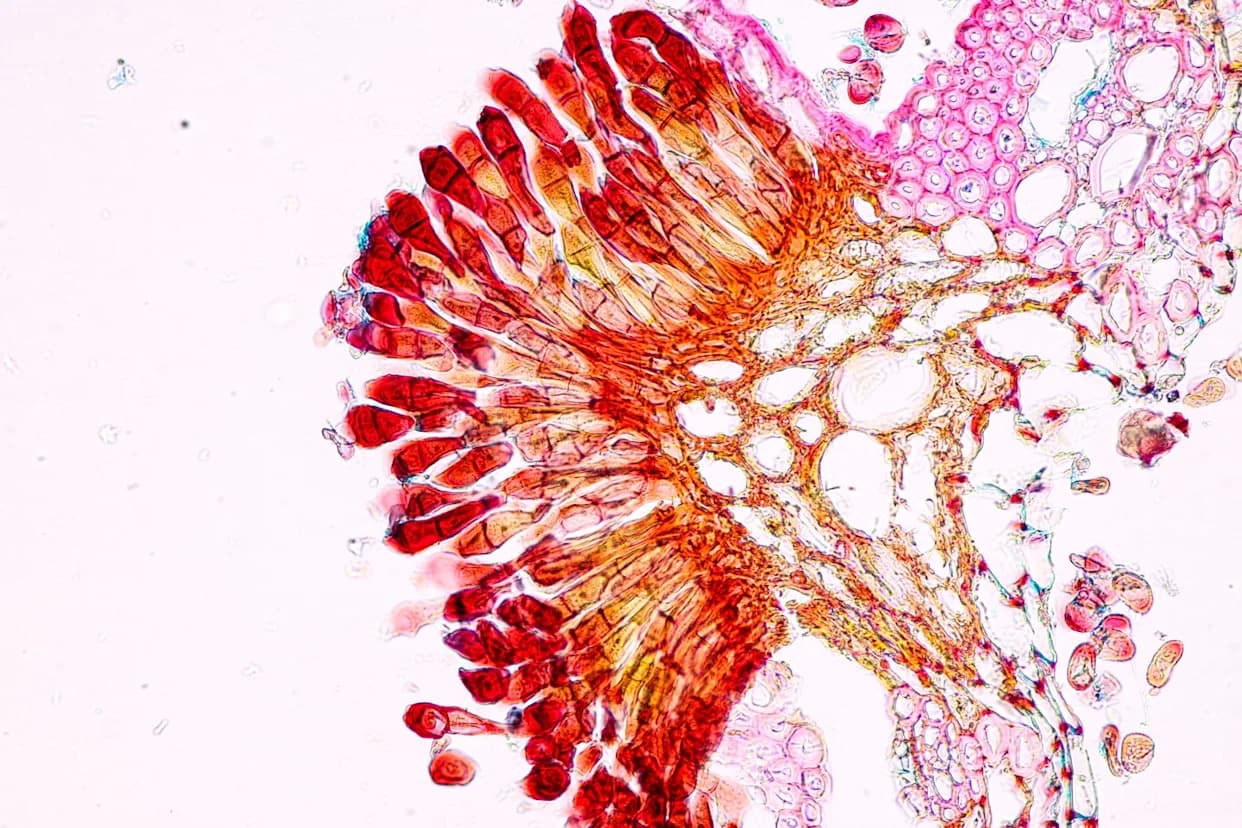

A team led by Martin Rahm at Chalmers University of Technology, writing in ACS Central Science, used extensive computational modeling to examine HCN in its solid state. They identified two reaction pathways on frozen HCN surfaces that convert HCN into its more reactive isomer, hydrogen isocyanide (HNC). On these ice surfaces, interactions between HCN and water can yield polymers, amino acids and nucleobases — the building blocks of proteins and DNA — that would be difficult to form under cold conditions otherwise.

Why this matters for astrobiology

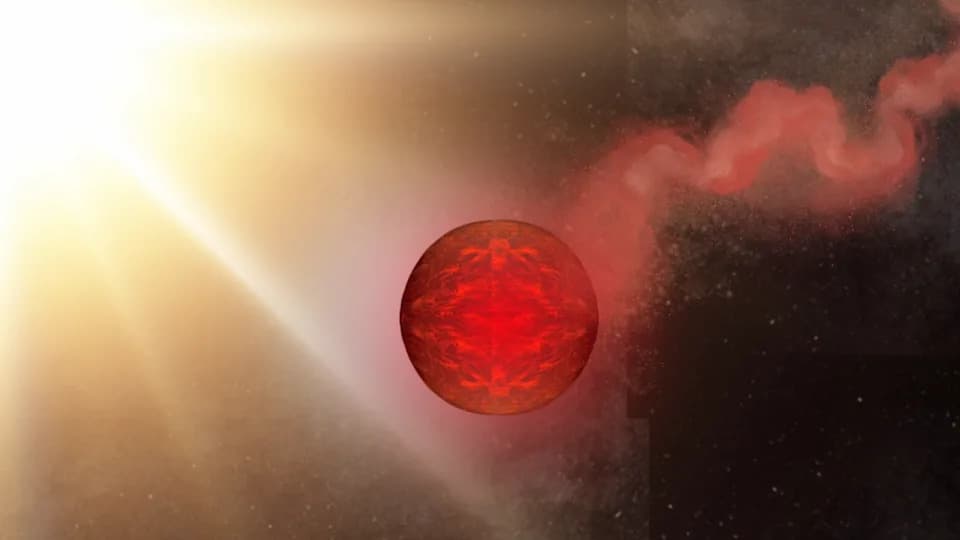

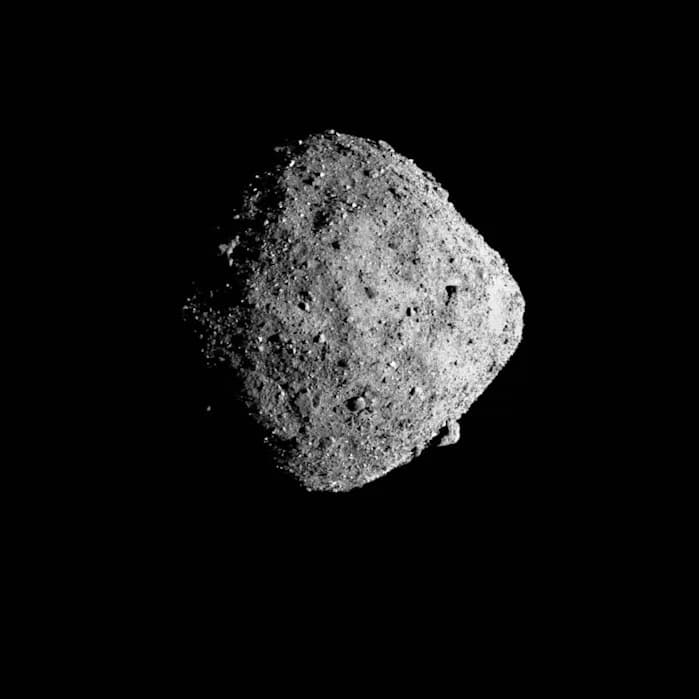

HCN is widespread in the cosmos: it appears in comets and in the atmospheres of planets and moons. For example, researchers have described a "cyanide belt" in Neptune's stratosphere, and Titan — Saturn’s largest moon — hosts cyanide-rich layers driven by ultraviolet chemistry in its hydrocarbon atmosphere. If frozen HCN can drive prebiotic chemistry, these environments become particularly interesting targets in the search for molecular precursors to life.

“We may never know precisely how life began, but understanding how some of its ingredients take shape is within reach,” Rahm said. “Hydrogen cyanide is likely one source of this chemical complexity, and we show that it can react surprisingly quickly in cold places.”

Context and caveats

The role of cyanide in prebiotic chemistry is not new. The Miller–Urey experiments of the 1950s identified cyanide as an intermediate in forming nucleobases, and a 2023 study suggested cyanide could react with carbon dioxide in early atmospheres to form carbon-based compounds. The new work extends these ideas by showing that frozen HCN surfaces may themselves be active reaction sites.

It’s important to remember that HCN is toxic to living organisms at high concentrations because it disrupts cellular respiration. In modern biology, small amounts of HCN have recognized roles — a recent South Dakota State University study found involvement in metabolism, neurotransmission and immune responses — and the enzyme rhodanese helps convert HCN into non-toxic salts for excretion. Those biological mechanisms are separate from the prebiotic chemistry that may have operated on early Earth or on other icy worlds.

Implications

While the results are based on modeling and need experimental confirmation under realistic planetary conditions, they open a plausible route by which simple, abundant molecules like HCN could contribute to chemical complexity. Mapping the distribution and properties of HCN ice on bodies such as Titan could help scientists better understand both chemical evolution and geological history — and refine where to look for life’s precursors beyond Earth.

Help us improve.