Researchers using advanced simulations that couple atmospheric chemistry and hydrodynamics estimate that Jupiter contains about 1.5 times the oxygen of the Sun. The finding supports formation models in which Jupiter accreted icy material near or beyond the solar system's snow line. The work also finds deep atmospheric circulation on Jupiter is slower than previously thought — with gases mixing over weeks rather than hours — with implications for heat transport, storm dynamics and interpretation of spacecraft data. Published Jan. 8 in the Planetary Science Journal.

New Simulations Suggest Jupiter Holds About 1.5× More Oxygen Than the Sun

Deep beneath Jupiter's turbulent cloud deck, researchers have found a crucial clue to how the planets in our solar system formed. A new study combining detailed atmospheric chemistry with fluid dynamics indicates Jupiter contains roughly one and a half times the oxygen of the Sun — a result that refines our picture of the gas giant's origins and the early solar system.

'It really shows how much we still have to learn about planets, even in our own solar system,'said Jeehyun Yang, a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Chicago and lead author of the study.

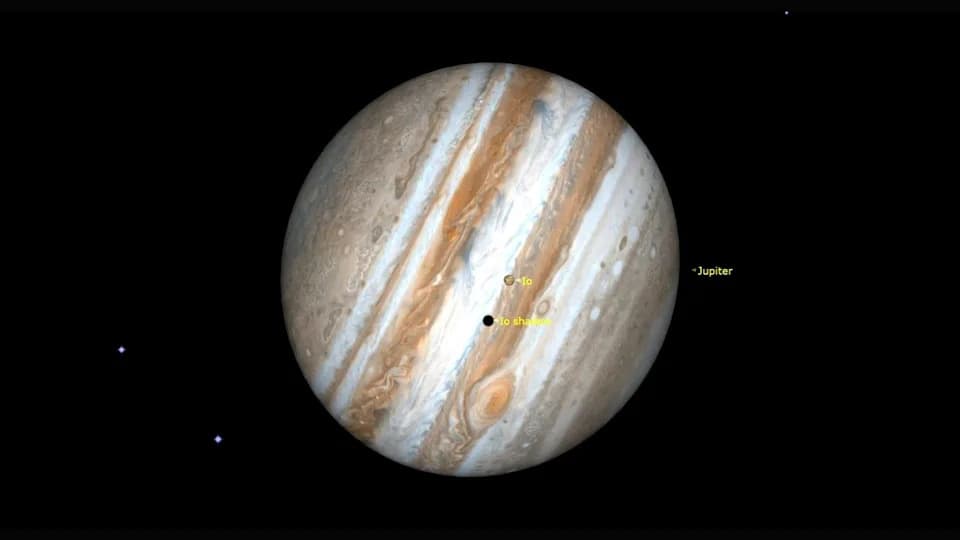

Jupiter's visible face is dominated by huge, long-lived storms — including the Great Red Spot, which is larger than Earth — but directly measuring the planet's deep atmosphere is extremely difficult. Spacecraft such as NASA's Juno probe can measure gravity and magnetic fields, and past missions sampled only the uppermost gas layers. Most of Jupiter's oxygen is tied up in water, which condenses far below the visible clouds and is out of reach for most orbiting instruments.

How the New Simulations Work

A team from the University of Chicago and NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory built the most detailed models yet of Jupiter's interior atmosphere. Their simulations couple atmospheric chemistry with hydrodynamics, tracking molecular composition, cloud condensates and the movement of gases and particles as material circulates from hot, deep layers to cooler, higher altitudes.

That integrated approach proved decisive. Earlier studies often separated chemistry and atmospheric motion, producing widely varying estimates for Jupiter's water and oxygen content. By modeling both processes together, the new work shows how water vapor, cloud formation and chemical reactions interact during slow vertical mixing.

Key Findings and Implications

The models point to a Jupiter enriched in oxygen by about 1.5 times relative to the Sun. This supports formation scenarios in which Jupiter accreted icy planetesimals early in the solar system's history, likely forming near or beyond the solar system's snow line where water ice was abundant. In that colder region, Jupiter could incorporate more oxygen-rich frozen material than the Sun.

The simulations also reveal that deep atmospheric circulation on Jupiter is slower than previously thought: gases may take weeks, not hours, to move between layers. Slower mixing affects how heat, storms and chemistry interact inside the planet and will influence interpretations of spacecraft observations and future probes that aim to measure water and other volatiles.

Because planets preserve chemical signatures of their birth environments, these results sharpen our understanding of planetary formation and will inform studies of exoplanets and the search for potentially habitable worlds. The study was published Jan. 8 in the Planetary Science Journal.

Help us improve.