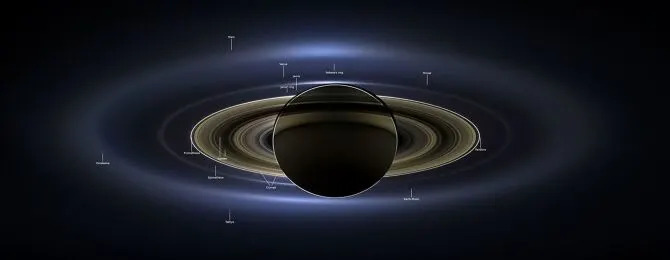

Reanalysis of Cassini radio data by a JPL team challenges the idea of a continuous subsurface ocean on Titan. The findings point to a stratified interior of ice and slush beneath a thick outer shell, which can explain observed tidal flexing and internal heat dissipation. Localized pockets of liquid water, possibly reaching about 20 degrees Celsius, may still exist and keep some astrobiological questions open. The results will inform planning for future missions such as NASA's Dragonfly.

Cassini Revisited: JPL Analysis Suggests Titan Has Slushy Layers, Not a Global Ocean

New processing of archival Cassini data by a team at NASA's Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL) challenges the long-held idea that Saturn's largest moon, Titan, hosts a global subsurface ocean. The refined analysis points instead to a complex, layered interior made of varying concentrations of water and ice — effectively slushy zones beneath a thick outer shell of solid ice.

What Cassini Originally Revealed

Scientists became intrigued after Cassini recorded unexpectedly large tidal flexing of Titan as it orbited Saturn. That degree of deformation was initially interpreted as evidence for a liquid layer beneath the ice, since a global ocean would make the moon more deformable than a solid body.

What The New Analysis Shows

Researchers reprocessed Cassini's radio-frequency signals using an improved noise-reduction technique that revealed subtle features previously buried in measurement noise. The refined data indicate strong internal energy dissipation consistent with frictional heating in layered, partially molten material rather than a single continuous liquid ocean.

In this model, alternating layers of relatively rigid ice and slushy mixtures of water and ice would absorb mechanical energy when Titan flexes, producing heat and explaining both the observed dissipation and the moon's apparent exterior flexibility.

Implications For Habitability

Although the picture shifts away from a global ocean, the team emphasizes that astrobiological possibilities remain. Localized pockets of liquid water could exist within the slushy layers, with temperatures the researchers estimate could reach about 20 degrees Celsius in some niches. These pockets could provide pathways for nutrients to cycle from Titan's rocky core toward the outer ice shell.

Lead researcher and JPL postdoctoral scientist Flavio Petricca said the analysis shows there should be pockets of liquid water, possibly as warm as 20 degrees Celsius, cycling nutrients from the moon’s rocky core through slushy layers of high-pressure ice toward the surface.

What This Means For Future Missions

The revised interpretation will affect scientific expectations and planning for future Titan missions, including NASA's Dragonfly rotorcraft, which the article notes is planned for launch in 2028. Mission teams may place greater emphasis on searching for localized warm pockets and signs of chemical exchange rather than targeting a single global sea.

Bottom line: Cassini's legacy data still have surprises. A cleaner look at the measurements suggests Titan is more of a layered, slushy world than the oceanic moon many once imagined — but pockets of habitability may persist.

Help us improve.