A new study ran 3,000 simulations to test whether a passing massive object could have reshaped the young solar system. Only about 1% of runs reproduced the current planetary arrangement, pointing to a narrow range of encounter parameters. The most likely culprit would be a body of roughly 3–30 Jupiter masses passing at about 20 AU (~1.86 billion miles), close enough to perturb planetary orbits without dismantling the system. The scenario complements existing ideas about early dynamical instability and planetary migration.

Rogue Planet or Brown Dwarf? How a Passing World May Have Reordered Our Solar System

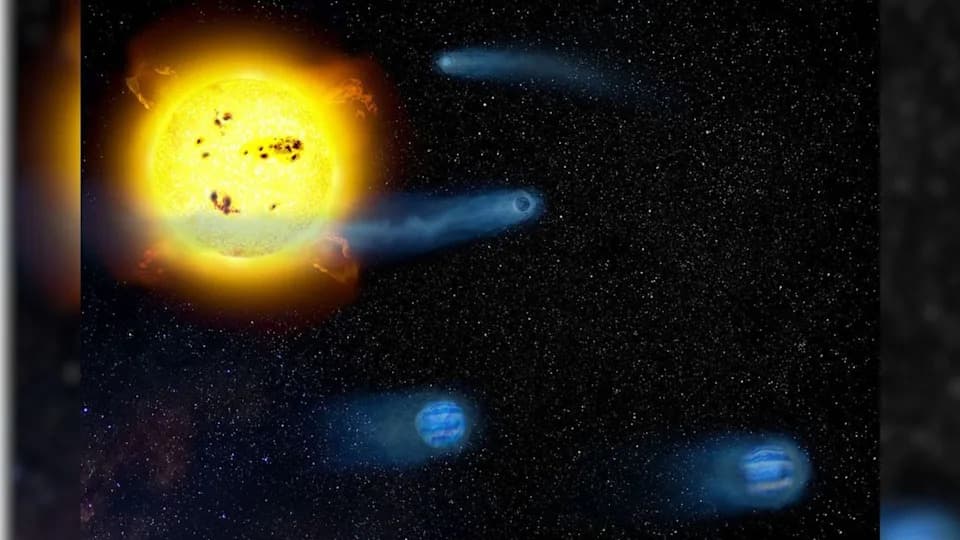

A roaming interloper sweeping into a neighborhood, upending orbits and changing futures is a familiar movie trope — and it may describe a dramatic episode in the early history of our solar system.

A long-standing question for astronomers is how the giant planets—Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune—came to occupy their current orbits. Evidence suggests these planets were once more tightly packed before a dynamical reshuffle gave them more room and even altered their ordering. What triggered that large-scale reconfiguration remains uncertain.

New research from the Laboratoire d'Astrophysique de Bordeaux and the Planetary Science Institute, led by Sean Raymond and Nathan Kaib, explored one compelling possibility: a close flyby by a massive object such as a rogue planet or a brown dwarf. The team ran an ensemble of 3,000 numerical simulations to test what kinds of encounters could reproduce a system like ours.

The simulations covered intruders with masses ranging from about that of Jupiter up to objects as massive as 10 Suns, and closest-approach distances from the Sun spanning 1–1,000 astronomical units (AU) (1 AU = Earth–Sun distance). From those thousands of runs, only 20 simulations — roughly 1% — produced a final orbital architecture comparable to the modern solar system.

The results imply a narrow window of effective parameters. Encounters that were too massive or passed too close typically ejected planets or severely distorted their orbits; intruders that were too light or passed at great distances produced negligible changes. From the successful cases, the authors infer that a passerby capable of rearranging the young system most likely had a mass between about 3 and 30 Jupiter masses (in the regime of a very large planet or a brown dwarf) and a closest approach on the order of ~20 AU — roughly 1.86 billion miles — close enough to perturb orbits without destroying the nascent planetary system.

These findings are broadly consistent with ideas about early dynamical instabilities (for example, scenarios related to the Nice model) that can drive planetary migration and reordering. While a close flyby is not the only plausible explanation, this study highlights a specific and testable pathway by which a single passing body could have triggered a lasting rearrangement.

Had such an interloper never arrived, our night sky and the configuration of the planets might look noticeably different today.

Help us improve.